The American Empire

1890s-1910s

Contents

The American Empire, 1890s-1910s:

Muckrakers

Illustration shows a “Standard Oil” storage tank as an octopus with many tentacles wrapped around the steel, copper, and shipping industries, as well as a state house, the U.S. Capitol, and one tentacle reaching for the White House. The only building not yet within reach of the octopus is the White House—President Teddy Roosevelt had won a reputation as a trust buster. Udo Keppler, “Next!” 1904. Library of Congress (LC-USZCN4-122).

|

American socialist leader Eugene Victor Debs, 1912. Library of Congress, LC-DIG-hec-01584.

Muckrakers

|

Muckrakers Quizlet

|

Review:

- What areas did Progressives think were in need of the greatest reform?

- How did women of the Progressive Era make progress and win the right to vote?

The Progressive Movement

Women protested silently in front of the White House for over two years before the passage of the Nineteenth Amendment. Here, women represent their colleges as they picket the White House in support of women’s suffrage. 1917. Library of Congress (LC-USZ62-31799).

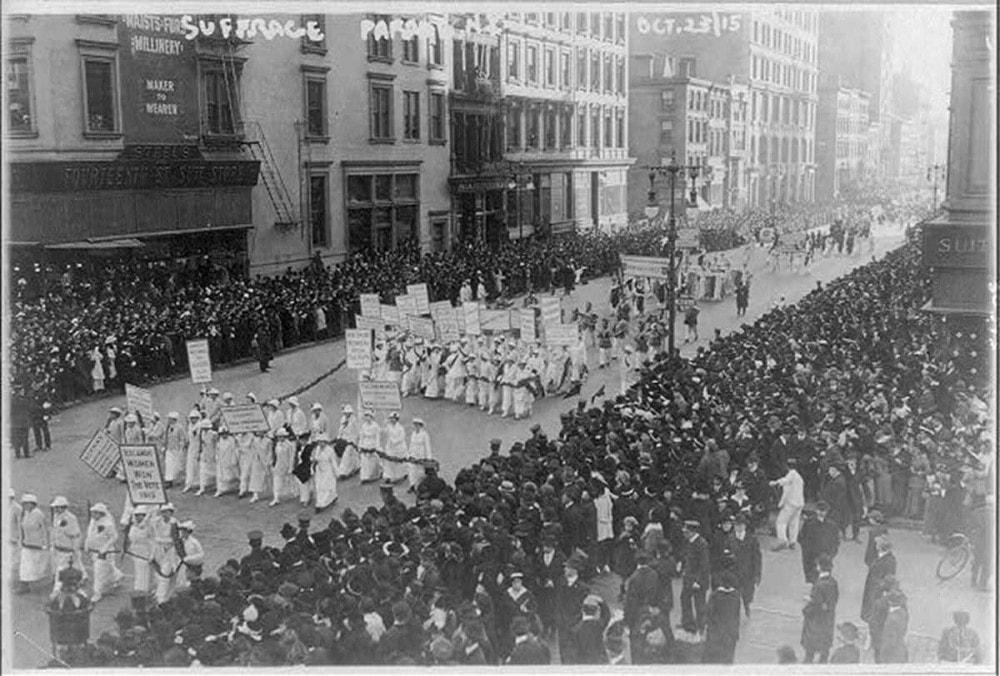

Suffragists campaigned tirelessly for the vote in the first two decades of the twentieth century, taking to the streets in public displays like this 1915 pre-election parade in New York City. During this one event, 20,000 women defied the gender norms that tried to relegate them to the private sphere and deny them the vote. 1915. Wikimedia.

Review:

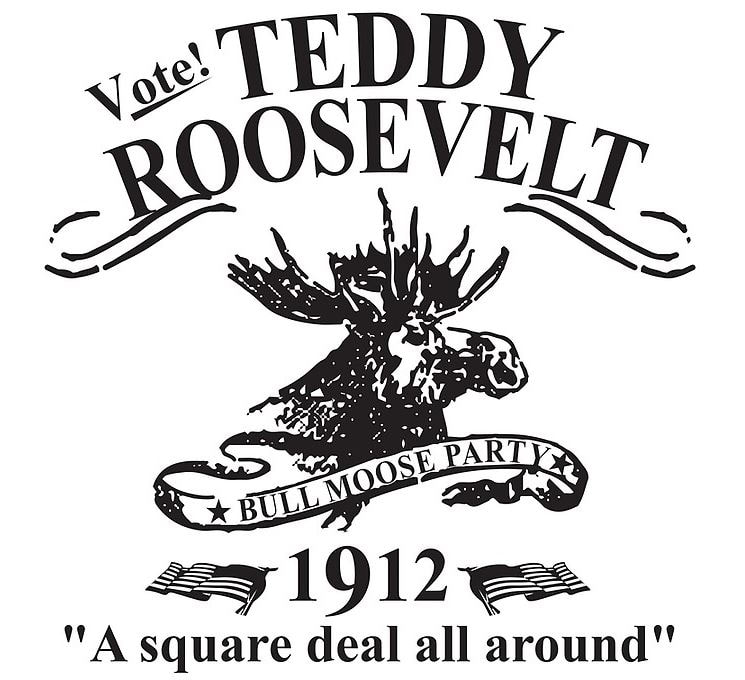

- What did Theodore Roosevelt think government should do for citizens?

- What steps did Wilson take to increase the government's role in the economy?

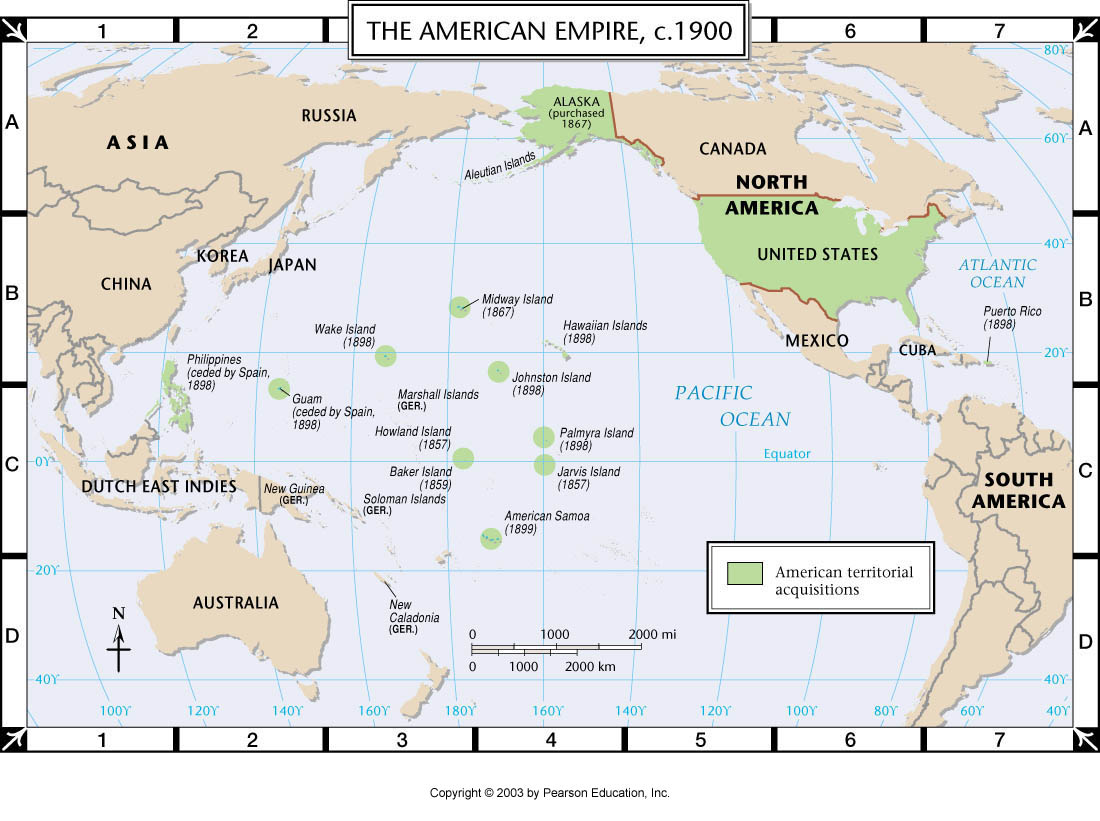

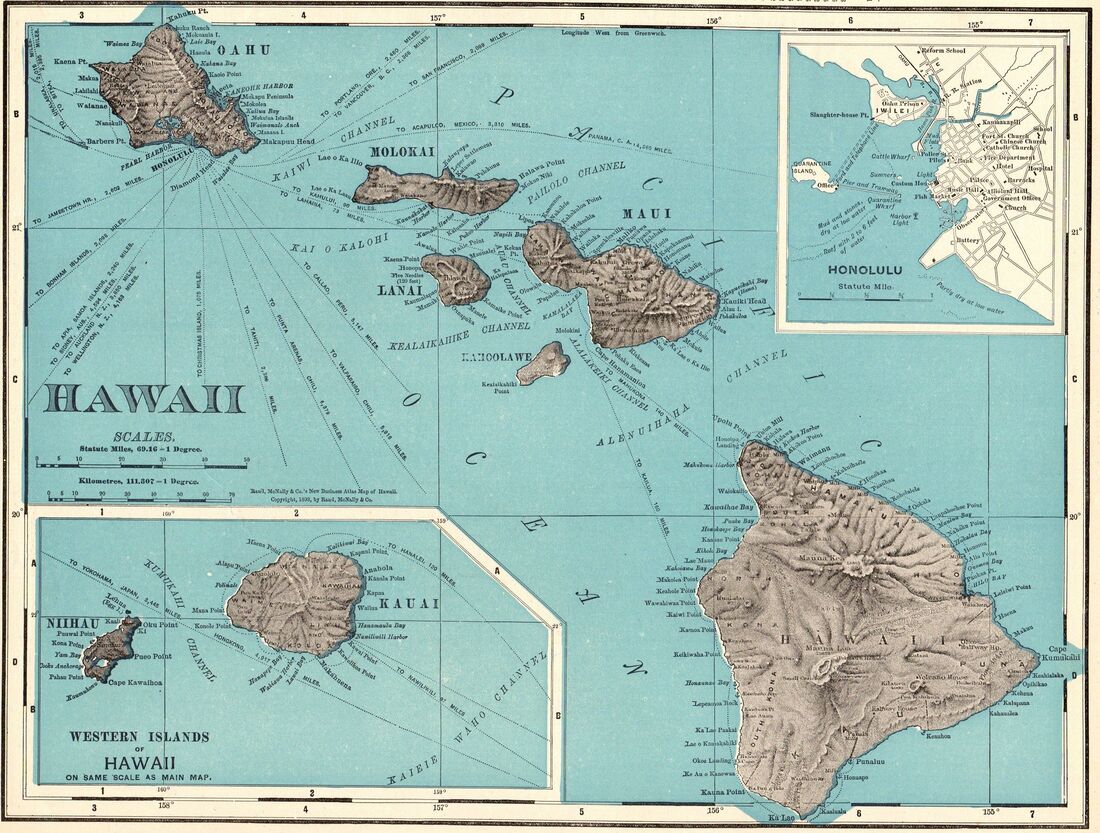

Becoming a Pacific Power

|

Liliuokalani, the last queen of Hawaii, was overthrown by American sugar planters in 1893. The short-lived Republic of Hawaii was formally annexed into the United States in 1898.

|

Review:

- How and why did the United States take a more active role in world affairs?

The Spanish-American War

Teddy Roosevelt, a politician turned soldier, gained fame after he and his Rough Riders took San Juan Hill. Images like this poster praised Roosevelt and the battle as Americans celebrated a “splendid little war.” 1899. Wikimedia.

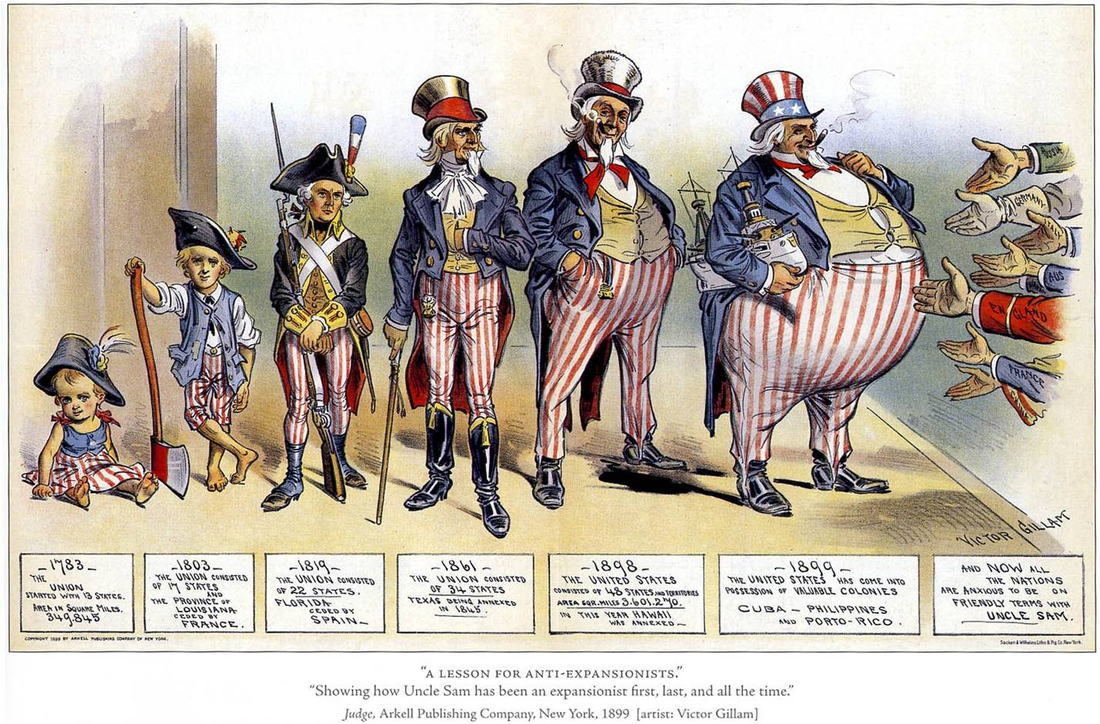

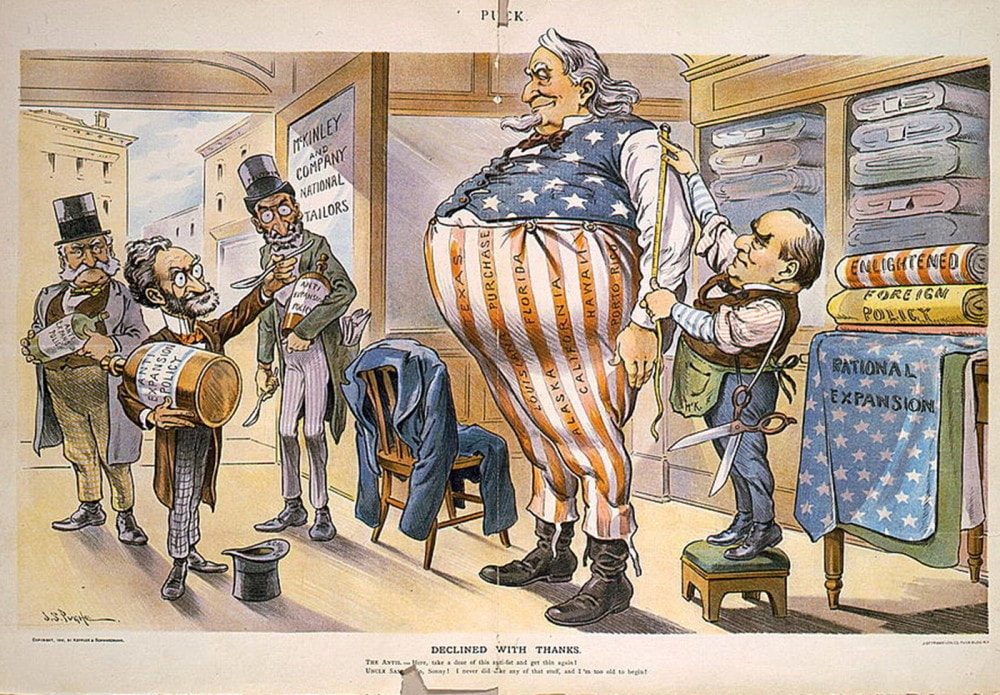

In this 1900 political cartoon, tailor President McKinley measures an obese Uncle Sam for larger clothing, while Anti-Expansionists like Joseph Pulitzer unsuccessfully offer Sam a weight-loss elixir. As the nation increased its imperialistic presence and mission, many like Pulitzer worried that America would grow too big for its own good.

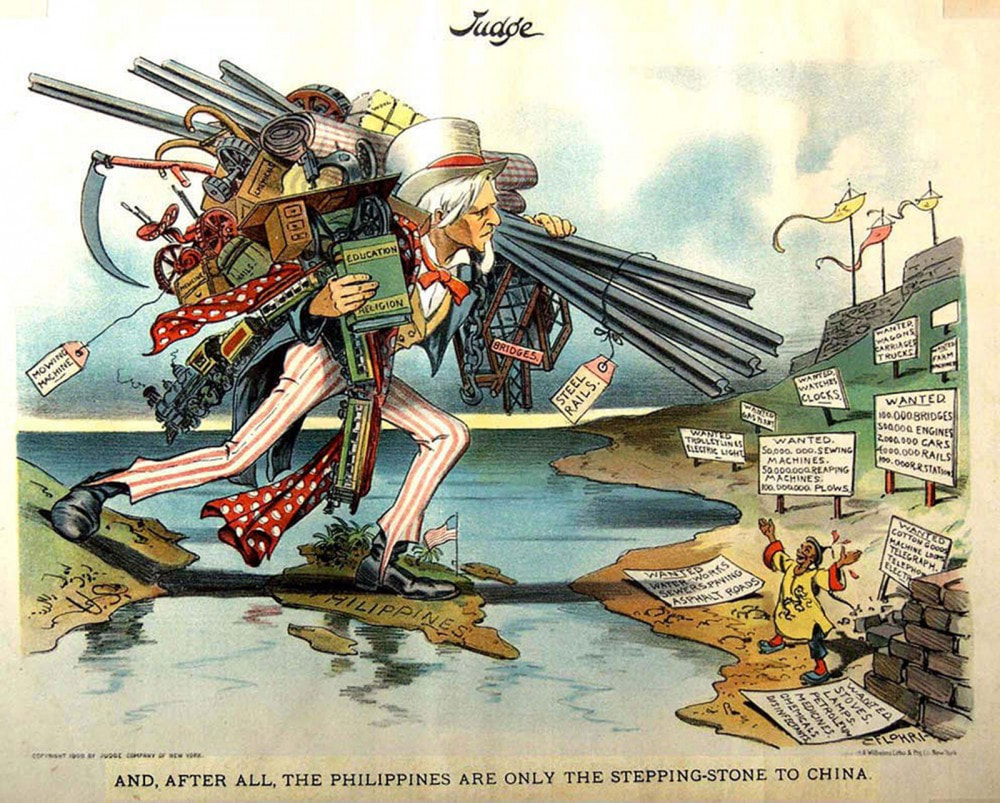

In this political cartoon, Uncle Sam, loaded with the implements of modern civilization, uses the Philippines as a stepping-stone to cross the Pacific to China, which excitedly awaits Sam’s arrival. Such cartoons captured Americans’ growing infatuation with imperialist and expansionist policies. C. 1900–1902. Wikimedia.

Review:

- What were the causes and effects of the Spanish-American War?

Big Stick Diplomacy

President Theodore Roosevelt, wielding a big stick, asserts American power in Latin America.

|

Big Stick Diplomacy Quizlet

|

|

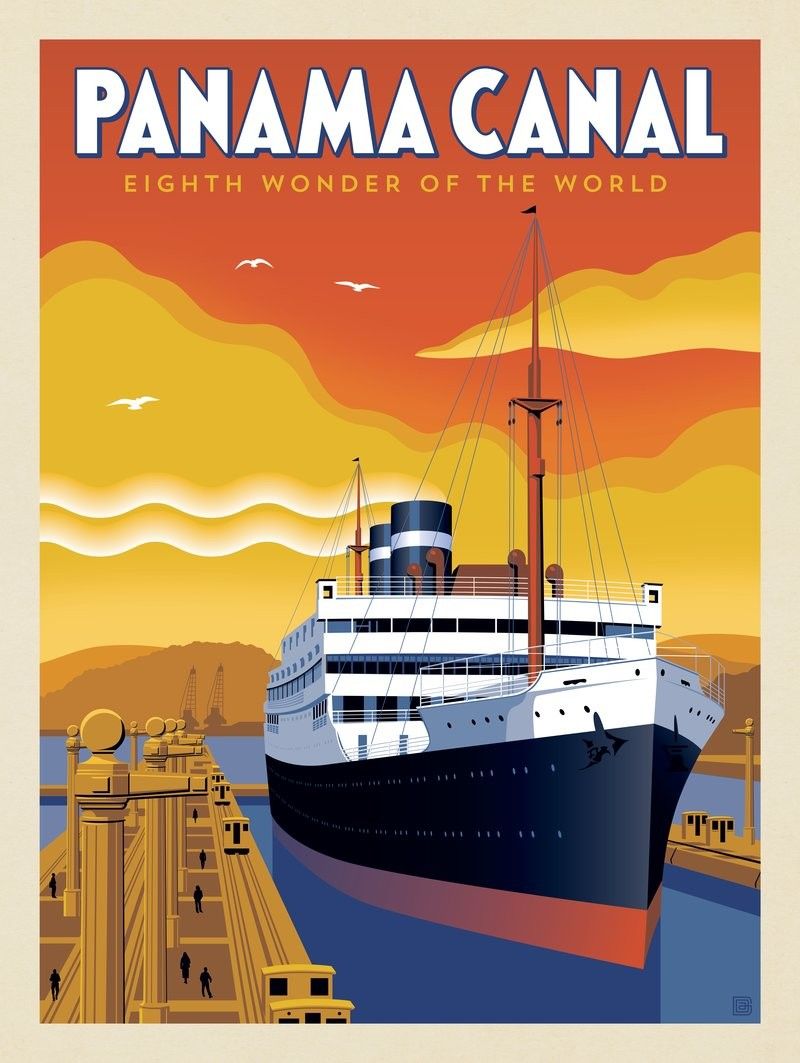

President Theodore Roosevelt, depicted digging through Panama in the cartoon and photographed seated in a steam shovel at the construction site, was the driving force behind construction of the Panama Canal.

|

Review:

- How did the United States extend its influence in Asia?

- What actions did the United States take to achieve its goals in Latin America?

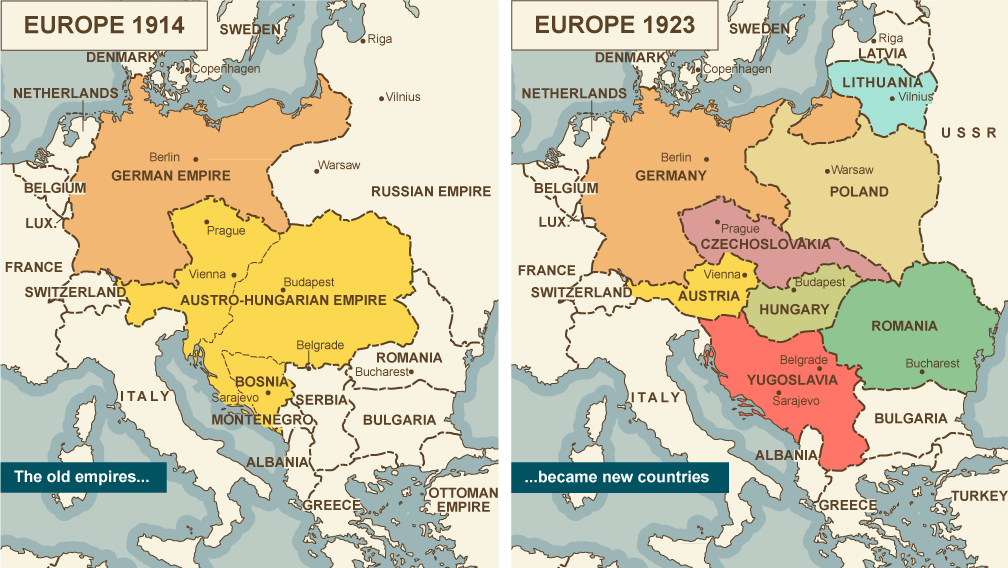

The Great War Before U.S. Entry

|

Soldiers wore gas masks to protect themselves from deadly chemical attacks.

|

British Mark I tank during the battle of the Somme, September 1916

|

|

The Great War Before U.S. Entry

|

The Great War Before U.S. Entry Quizlet

|

Review:

- What caused the First World War, and why did the US enter the war?

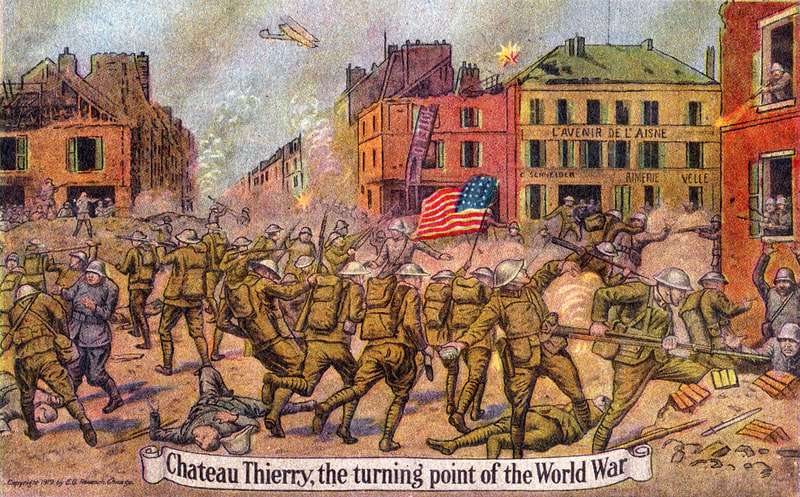

America in the Great War

|

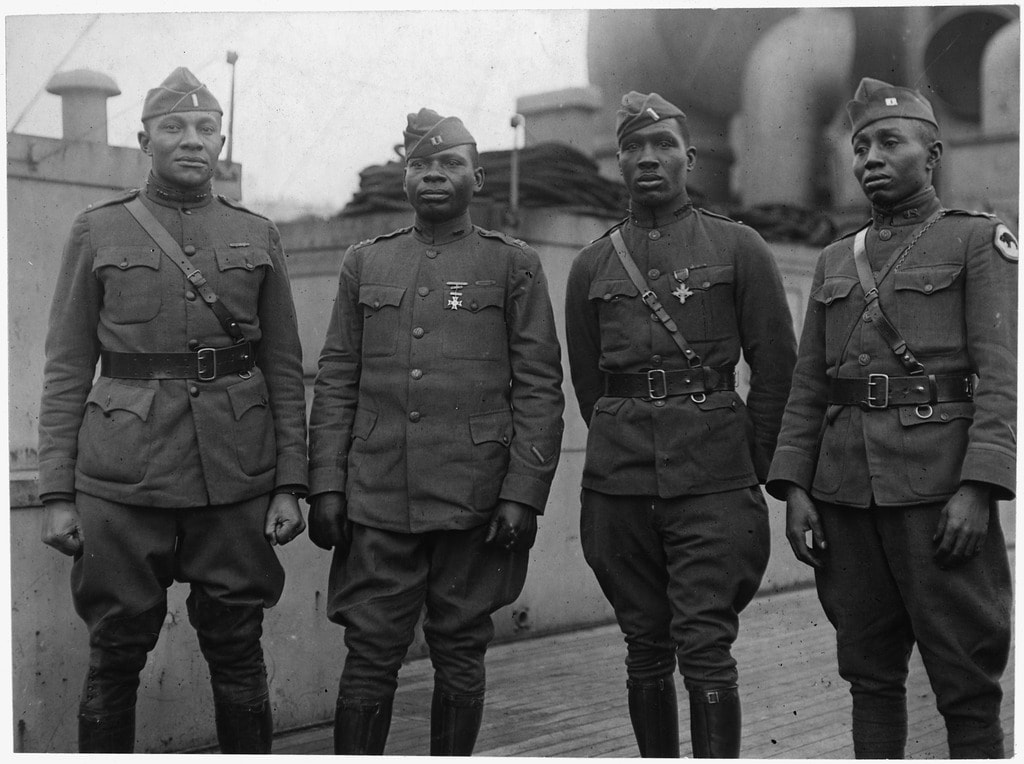

officers of the American 366th Infantry

|

member of the 369th Infantry, the "Harlem Hellfighters"

|

The Boy Scouts of America charge up Fifth Avenue in New York City in a “Wake Up, America” parade to support recruitment efforts. Nearly sixty thousand people attended this single parade. Wikimedia.

With America still at war in World War I, President Wilson sent American troops to Siberia during the Russian civil war to oppose the Bolsheviks. This August 1918 photograph shows American soldiers in Vladivostok parading before the building occupied by the staff of the Czecho-Slovaks. To the left, Japanese marines stand to attention as the American troops march. Wikimedia.

Review:

- What caused the First World War, and why did the US enter the war?

- How did the war affect Americans at home?

The Treaty of Versailles

"The Big Four" - David Lloyd George of Britain, Vittorio Orlando of Italy, Georges Clemenceau of France, and Woodrow Wilson of the U.S. - made all the major decisions at the Paris Peace Conference.

Striking steel mill workers holding bulletins in Chicago, Illinois, September 22, 1919. ExplorePAhistory.com

Review:

- How did Americans affect the end of World War I and its peace settlements?

- What political, economic, and social effects did World War I have on the US?

Assignments and Readings

|

|

Your browser does not support viewing this document. Click here to download the document.

| ||||||

|

|

Your browser does not support viewing this document. Click here to download the document.

| ||||||

|

|

Your browser does not support viewing this document. Click here to download the document.

| ||||||

Imperialism Reading Packet

|

Your browser does not support viewing this document. Click here to download the document.

|

Your browser does not support viewing this document. Click here to download the document.

| ||||||||||||

Visit Beautiful ...

| |||||||

|

Here are some of the greatest movie posters of all time for reference. Note how most of them have 1) an iconic image, 2) list the stars, directors, and other key filmmakers, and 3) have a catchy tagline.

|

Here are some great vintage posters from the Golden Age of Travel. Note how each captures the spirit of what you see or experience at each locale. Many of these lack a tagline but you should include one.

|

Here are examples of past student work. See if you can top it!

|

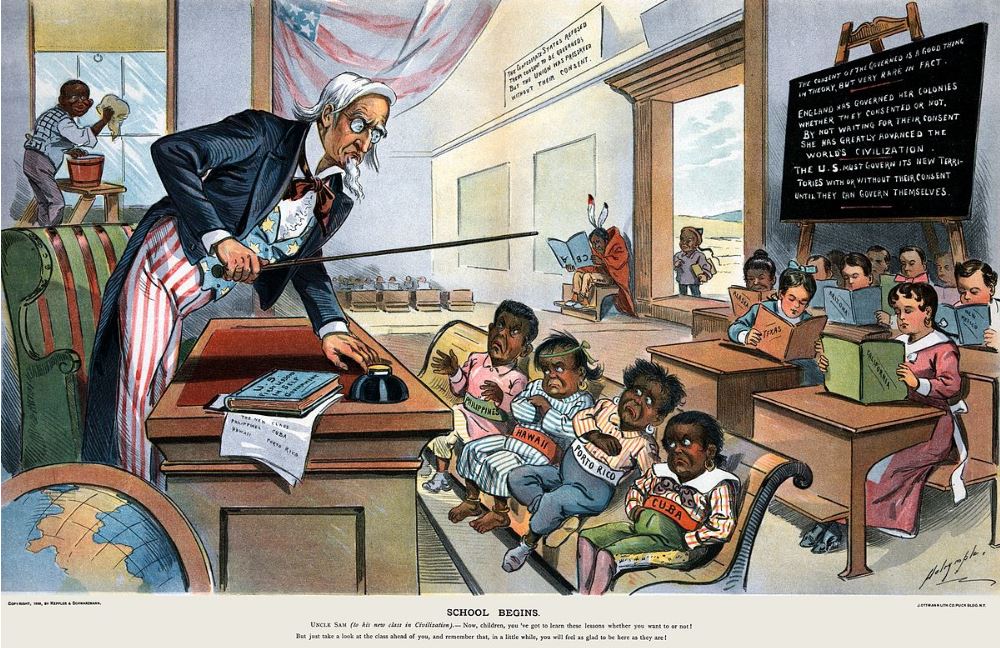

School Begins

In this 1899 cartoon published, Uncle Sam lectures his new students: The Philippines, Hawaii, Puerto Rico, and, Cuba. Past and potentially future U.S. acquisitions fill the rest of the classroom.

"School Begins", Puck magazine, January 25, 1899

Click here for a high resolution version of the cartoon.

Caption: "School Begins. Uncle Sam (to his new class in Civilization): Now, children, you've got to learn these lessons whether you want to or not! But just take a look at the class ahead of you, and remember that, in a little while, you will feel as glad to be here as they are!"

Blackboard: The consent of the governed is a good thing in theory, but very rare in fact. — England has governed her colonies whether they consented or not. By not waiting for their consent she has greatly advanced the world's civilization. — The U.S. must govern its new territories with or without their consent until they can govern themselves.

Poster on Wall: The Confederated States refused their consent to be governed, but the Union was preserved without their consent.

Book: U.S. — First Lessons in Self Government

Analysis Questions:

Click here for a high resolution version of the cartoon.

Caption: "School Begins. Uncle Sam (to his new class in Civilization): Now, children, you've got to learn these lessons whether you want to or not! But just take a look at the class ahead of you, and remember that, in a little while, you will feel as glad to be here as they are!"

Blackboard: The consent of the governed is a good thing in theory, but very rare in fact. — England has governed her colonies whether they consented or not. By not waiting for their consent she has greatly advanced the world's civilization. — The U.S. must govern its new territories with or without their consent until they can govern themselves.

Poster on Wall: The Confederated States refused their consent to be governed, but the Union was preserved without their consent.

Book: U.S. — First Lessons in Self Government

Analysis Questions:

- Describe Uncle Sam's body language.

- Who are the new students in the front row?

- Who are the older students seated further back?

- How do the new students differ from the older students?

- What is the "consent of the governed"?

- Who does the figure outside the door represent?

- Who does the figure seated near the door represent?

- Who does the figure in the upper left corner represent?

- What do these three figures say about the state of race relations in the U.S. in 1899?

- Is the cartoon pro-imperialist or anti-imperialist? WHY did you arrive at this conclusion?

Primary Sources

Booker T. Washington & W.E.B. DuBois on Black Progress (1895, 1903)

Booker T. Washington, born a slave in Virginia in 1856, founded the Tuskegee Institute in Alabama in 1881 and became a leading advocate of African American progress. Introduced as “a representative of Negro enterprise and Negro civilization,” Washington delivered the following remarks, sometimes called the “Atlanta Compromise” speech, at the Cotton States and International Exposition in Atlanta in 1895.

Jane Addams, “The Subjective Necessity for Social Settlements” (1892)

Hull House, Chicago’s famed “settlement house,” was designed to uplift urban populations. Here, Addams explains why she believes reformers must “add the social function to democracy.” As Addams explained, Hull House “was opened on the theory that the dependence of classes on each other is reciprocal.”

Eugene Debs, “How I Became a Socialist” (April, 1902)

A native of Terre Haute, Indiana, Eugene V. Debs began working as a locomotive fireman (tending the fires of a train’s steam engine) as a youth in the 1870s. His experience in the American labor movement later led him to socialism. In the early-twentieth century, as the Socialist Party of America’s candidate, he ran for the presidency five times and twice earned nearly one-million votes. He was America’s most prominent socialist. In 1902, a New York paper asked Debs how he became a socialist. This is his answer.

Walter Rauschenbusch, Christianity and the Social Crisis (1907)

Walter Rauschenbusch, a Baptist minister and theologian, advocated for a “social gospel.” Here, he explains why he believes Christianity must address social questions.

Alice Stone Blackwell, Answering Objections to Women’s Suffrage (1917)

Alice Stone Blackwell was a feminist activist and writer. In an edited volume published in 1917, Blackwell responded to popular anti-women’s-suffrage arguments.

Woodrow Wilson on the “New Freedom,” 1912

Woodrow Wilson campaigned for the presidency in 1912 as a progressive democrat. Wilson argued that changing economic conditions demanded new and aggressive government policies–he called his political program “the New Freedom”– to preserve traditional American liberties.

“Next!” (1904)

Illustration shows a “Standard Oil” storage tank as an octopus with many tentacles wrapped around the steel, copper, and shipping industries, as well as a state house, the U.S. Capitol, and one tentacle reaching for the White House. The only building not yet within reach of the octopus is the White House—President Teddy Roosevelt had won a reputation as a “trust buster.”

“College Day on the Picket Line” (1917)

Women protested silently in front of the White House for over two years before the passage of the Nineteenth Amendment. Here, women represent their colleges as they picket the White House in support of women’s suffrage. 1917.

William McKinley on American Expanionism (1903)

After the surrender of the Spanish in the Spanish-American War, the United States assumed control of the Philippines and struggled to contain an anti-American insurgency.

Rudyard Kipling, “The White Man’s Burden” (1899)

As the United States waged war against Filipino insurgents, the British writer and poet Rudyard Kipling urged the Americans to take up “the white man’s burden.”

James D. Phelan, “Why the Chinese Should Be Excluded” (1901)

James D. Phelan, the mayor of San Francisco, penned the following article to drum up support for the extension of laws prohibiting Chinese immigration.

William James on “The Philippine Question” (1903)

Many Americans opposed imperialist actions. Here, the philosopher William James explains his opposition in the light of history.

Mark Twain, “The War Prayer” (ca.1904-5)

The American writer Mark Twain wrote the following satire in the glow of America’s imperial interventions.

Woodrow Wilson Requests War (April 2, 1917)

In this speech before Congress, President Woodrow Wilson made the case for America’s entry into World War I.

Alan Seeger on World War I (1914; 1916)

The poet Alan Seeger, born in New York and educated at Harvard University, lived among artists and poets in Greenwich Village, New York and Paris, France. When the Great War engulfed Europe, and before the United State entered the fighting, Seeger joined the French Foreign Legion. He would be killed at the Battle of the Somme in 1916. His wartime experiences would anticipate those of his countrymen, a million of whom would be deployed to France. Seeger’s writings were published posthumously. The first selection is excerpted from a letter Seeger wrote to the New York Sun in 1914; the second is from his collection of poems, published in 1916.

The Sedition Act of 1918 (1918)

Passed by Congress in May 1918 and signed into law by President Woodrow Wilson, the Sedition Act of 1918 amended the Espionage Act of 1917 to include greater limitations on war-time dissent.

Emma Goldman on Patriotism (July 9, 1917)

The Anarchist Emma Goldman was tried for conspiring to violate the Selective Service Act. The following is an excerpt from her speech to the court, in which she explains her views on patriotism.

W.E.B DuBois, “Returning Soldiers” (May, 1919)

In the aftermath of World War I, W.E.B. DuBois urged returning soldiers to continue fighting for democracy at home.

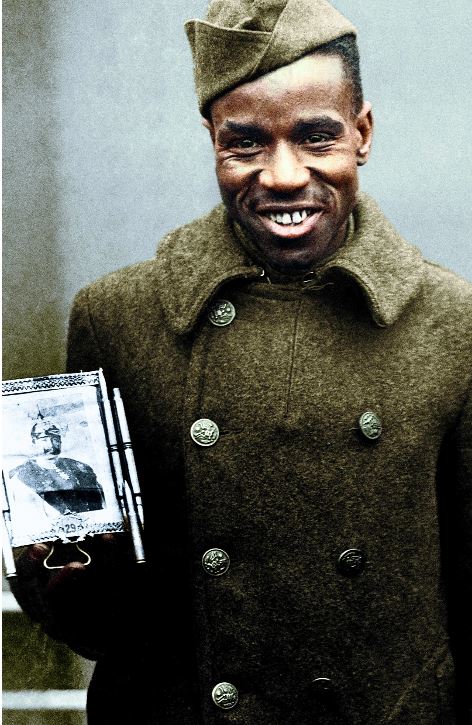

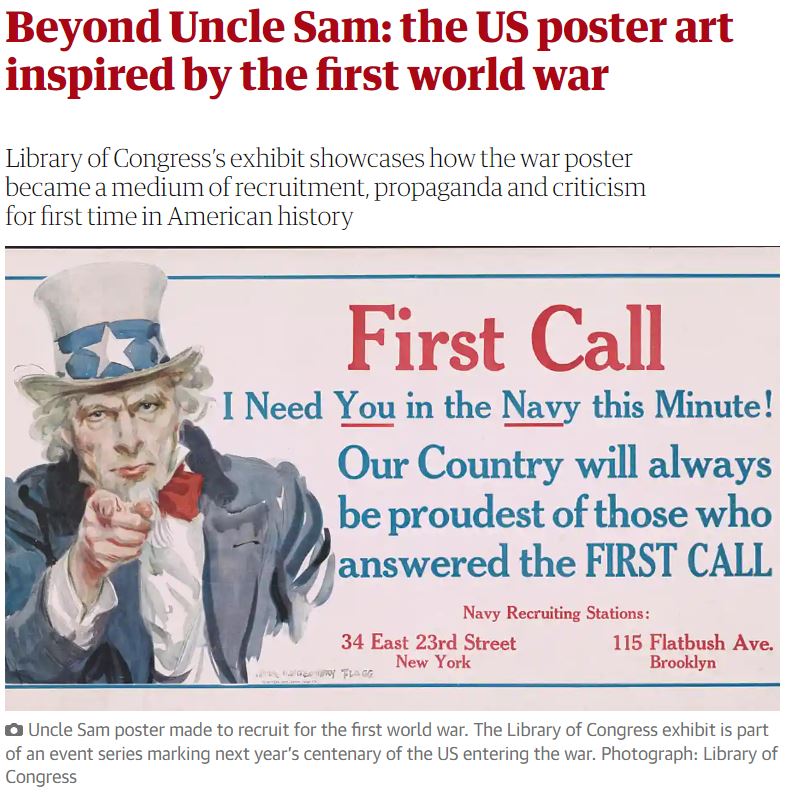

“I Want You” (1917)

In this war poster, Uncle Sam points his finger at the viewer and says, “I want you for U.S. Army.” The poster was printed with a blank space to attach the address of the “nearest recruiting station.” Click on the image to view the full poster.

Booker T. Washington, born a slave in Virginia in 1856, founded the Tuskegee Institute in Alabama in 1881 and became a leading advocate of African American progress. Introduced as “a representative of Negro enterprise and Negro civilization,” Washington delivered the following remarks, sometimes called the “Atlanta Compromise” speech, at the Cotton States and International Exposition in Atlanta in 1895.

Jane Addams, “The Subjective Necessity for Social Settlements” (1892)

Hull House, Chicago’s famed “settlement house,” was designed to uplift urban populations. Here, Addams explains why she believes reformers must “add the social function to democracy.” As Addams explained, Hull House “was opened on the theory that the dependence of classes on each other is reciprocal.”

Eugene Debs, “How I Became a Socialist” (April, 1902)

A native of Terre Haute, Indiana, Eugene V. Debs began working as a locomotive fireman (tending the fires of a train’s steam engine) as a youth in the 1870s. His experience in the American labor movement later led him to socialism. In the early-twentieth century, as the Socialist Party of America’s candidate, he ran for the presidency five times and twice earned nearly one-million votes. He was America’s most prominent socialist. In 1902, a New York paper asked Debs how he became a socialist. This is his answer.

Walter Rauschenbusch, Christianity and the Social Crisis (1907)

Walter Rauschenbusch, a Baptist minister and theologian, advocated for a “social gospel.” Here, he explains why he believes Christianity must address social questions.

Alice Stone Blackwell, Answering Objections to Women’s Suffrage (1917)

Alice Stone Blackwell was a feminist activist and writer. In an edited volume published in 1917, Blackwell responded to popular anti-women’s-suffrage arguments.

Woodrow Wilson on the “New Freedom,” 1912

Woodrow Wilson campaigned for the presidency in 1912 as a progressive democrat. Wilson argued that changing economic conditions demanded new and aggressive government policies–he called his political program “the New Freedom”– to preserve traditional American liberties.

“Next!” (1904)

Illustration shows a “Standard Oil” storage tank as an octopus with many tentacles wrapped around the steel, copper, and shipping industries, as well as a state house, the U.S. Capitol, and one tentacle reaching for the White House. The only building not yet within reach of the octopus is the White House—President Teddy Roosevelt had won a reputation as a “trust buster.”

“College Day on the Picket Line” (1917)

Women protested silently in front of the White House for over two years before the passage of the Nineteenth Amendment. Here, women represent their colleges as they picket the White House in support of women’s suffrage. 1917.

William McKinley on American Expanionism (1903)

After the surrender of the Spanish in the Spanish-American War, the United States assumed control of the Philippines and struggled to contain an anti-American insurgency.

Rudyard Kipling, “The White Man’s Burden” (1899)

As the United States waged war against Filipino insurgents, the British writer and poet Rudyard Kipling urged the Americans to take up “the white man’s burden.”

James D. Phelan, “Why the Chinese Should Be Excluded” (1901)

James D. Phelan, the mayor of San Francisco, penned the following article to drum up support for the extension of laws prohibiting Chinese immigration.

William James on “The Philippine Question” (1903)

Many Americans opposed imperialist actions. Here, the philosopher William James explains his opposition in the light of history.

Mark Twain, “The War Prayer” (ca.1904-5)

The American writer Mark Twain wrote the following satire in the glow of America’s imperial interventions.

Woodrow Wilson Requests War (April 2, 1917)

In this speech before Congress, President Woodrow Wilson made the case for America’s entry into World War I.

Alan Seeger on World War I (1914; 1916)

The poet Alan Seeger, born in New York and educated at Harvard University, lived among artists and poets in Greenwich Village, New York and Paris, France. When the Great War engulfed Europe, and before the United State entered the fighting, Seeger joined the French Foreign Legion. He would be killed at the Battle of the Somme in 1916. His wartime experiences would anticipate those of his countrymen, a million of whom would be deployed to France. Seeger’s writings were published posthumously. The first selection is excerpted from a letter Seeger wrote to the New York Sun in 1914; the second is from his collection of poems, published in 1916.

The Sedition Act of 1918 (1918)

Passed by Congress in May 1918 and signed into law by President Woodrow Wilson, the Sedition Act of 1918 amended the Espionage Act of 1917 to include greater limitations on war-time dissent.

Emma Goldman on Patriotism (July 9, 1917)

The Anarchist Emma Goldman was tried for conspiring to violate the Selective Service Act. The following is an excerpt from her speech to the court, in which she explains her views on patriotism.

W.E.B DuBois, “Returning Soldiers” (May, 1919)

In the aftermath of World War I, W.E.B. DuBois urged returning soldiers to continue fighting for democracy at home.

“I Want You” (1917)

In this war poster, Uncle Sam points his finger at the viewer and says, “I want you for U.S. Army.” The poster was printed with a blank space to attach the address of the “nearest recruiting station.” Click on the image to view the full poster.

Slideshows

Videos

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Biography of America "Episode 14: Industrial Supremacy" - https://www.learner.org/series/biographyofamerica/prog14/transcript/index.html

Biography of America "Episode 15: The New City" - https://www.learner.org/series/biographyofamerica/prog15/transcript/index.html

Digital History Textbook

The Twentieth Century

An overview of the far-reaching economic and social changes that transformed American society in the 20th century, including innovations in science and technology, economic productivity, mass communication and mass entertainment, health and living standards, the role of government, gender roles, and conceptions of freedom.

Introduction

The United States in 1900

Twentieth Century Revolutions

The Progressive Era

Progressivism is an umbrella label for a wide range of economic, political, social, and moral reforms. These included efforts to outlaw the sale of alcohol; regulate child labor and sweatshops; scientifically manage natural resources; insure pure and wholesome water and milk; Americanize immigrants or restrict immigration altogether; and bust or regulate trusts. Drawing support from the urban, college-educated middle class, Progressive reformers sought to eliminate corruption in government, regulate business practices, address health hazards, improve working conditions, and give the public more direct control over government through direct primaries to nominate candidates for public office, direct election of Senators, the initiative, referendum, and recall, and women's suffrage.By the beginning of the twentieth century, muckraking journalists were calling attention to the exploitation of child labor, corruption in city governments, the horror of lynching, and the ruthless business practices employed by businessmen like John D. Rockefeller. At the local level, many Progressives sought to suppress red-light districts, expand high schools, construct playgrounds, and replace corrupt urban political machines with more efficient system of municipal government. At the state level, Progressives enacted minimum wage laws for women workers, instituted industrial accident insurance, restricted child labor, and improved factory regulation.

At the national level, Congress passed laws establishing federal regulation of the meat-packing, drug, and railroad industries, and strengthened anti-trust laws. It also lowered the tariff, established federal control over the banking system, and enacted legislation to improve working condition. Four constitutional amendments were adopted during the Progressive era, which authorized an income tax, provided for the direct election of senators, extended the vote to women, and prohibited the manufacture and sale of alcoholic beverages.

Jane Addams: Champion for the Working Poor

Progressivism

A New Era

The Roots of Progressivism

Herbert Croly and The Promise of American Life

Newsies

Municipal Progressivism

State Progressivism

National Progressivism

Theodore Roosevelt

Anti-Trust

Government Regulation

Conservation

Taft

Income Tax

Wilson

Along the Color Line

The period late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries represented the nadir of American race relations. Nine-tenths of African Americans lived in the South, and most supported themselves as tenant farmers or sharecroppers. Most southern and border states instituted a legal system of segregation, relegating African Americans to separate schools and other public accommodations. Under the Mississippi Plan, involving the use of poll taxes and literacy tests, African Americans were deprived of the vote. The Supreme Court stripped the 14th and 15th Amendments of their meaning, especially in the 1896 case of Plessy v. Ferguson, which declared that “separate but equal” facilities were permissible under the 14th Amendment. Each year approximately a hundred African Americans were lynched.Booker T. Washington, the most prominent black leader, argued that African Americans should make themselves economically indispensable to southern whites, cooperate with whites, and accommodate themselves to white supremacy. But other figures adopted a more activist stance, such as the anti-lynching crusader Ida B. Wells, and W.E.B. DuBois, a founder of the NAACP, who demanded an end to caste distinctions based on race.

A tight labor market during World War I triggered the “Great Migration” of African Americans to the North, which continued into the 1920s. But the movement of blacks out of the South was met by racial violence in Chicago, East St. Louis, Houston, Tulsa, and other cities.

The Great Migration was accompanied by new efforts at black political and economic organization and cultural expression, including Marcus Garvey's Universal Negro Improvement Association, which emphasized racial pride and economic self-help, and the Harlem Renaissance, a literary and artistic movement.

The State of African Americans in the South

Lynching

Convict Lease System

Jim Crow and the Courts

Plessy v. Ferguson

Segregation and Disfranchisement

Booker T. Washington and the Politics of Accommodation

Conclusion

The Struggle for Women's Suffrage

Among the most radical of all struggles in American history is the on-going struggle of women for full equality. The ideals of the American Revolution raised women's expectations, inspired some of the first explicit demands for equality, and witnessed the establishment of female academies to improve women's education. By the early 19th century, American women had the highest female literacy rate in the world.But as American states widened suffrage to include virtually all white males, they began denying the vote to free blacks and, in New Jersey, to women, who had briefly won this privilege following the Revolution. In the 1820s and for decades to come married women could not own property, make contracts, bring suits, or sit on juries. They could be legally beaten by their husbands and were required to submit to their husbands' sexual demands.

During the early 19th century, however, a growing number of women became convinced that they had a special mission and responsibility to purify and reform American society. Women were at the forefront of efforts to establish public schools, abolish slavery, and curb drinking. But faced with discrimination within the antislavery movement, Elizabeth Cady Stanton and others organized the first Women's Rights Convention in history in Seneca Falls, New York, in 1848.

The quest for full equality involved not only the struggle for the vote, but for divorce, access to higher education, the professions, and other occupations, as well as birth control and abortion. Women have had to overcome laws and customs that discriminated on the basis of sex in order to overcome the oldest form of exploitation and subordination.

"Failure is Impossible"

72 Years

The Drive for the Vote Begins

The Movement Splits

The First Breakthroughs

New Arguments and New Constituencies

Opponents of Suffrage

The Final Push

Did the Vote Make a Difference?

Political Firsts

Birth Control

United States Becomes a World Power

This chapter examines the reasons why the United States adopted a more aggressive foreign policy at the end of the 19th century; the causes, military history, and consequences of the Spanish American War; and early 20th century U.S. involvement in China, the Caribbean, and Latin America.

"A Man, A Plan, A Canal, Panama"

The United States Becomes a World Power

The Annexation of Hawaii

The Spanish American War

The Philippines

Policing the Caribbean and Central America

Intervention in Haiti

America at War: World War I

This chapter examines the war’s causes, the reasons why the United States intervened in the conflict, how American industry was mobilized for war, wartime propaganda and political repression, and the social changes and unrest produced by the war.

Sgt. York

World War I

The Road to War

The Guns of August

The Lusitania

The United States Enters the War:

Over There: American Doughboys Go to War

Over Here: World War I on the Home Front

The Espionage and Sedition Acts

An overview of the far-reaching economic and social changes that transformed American society in the 20th century, including innovations in science and technology, economic productivity, mass communication and mass entertainment, health and living standards, the role of government, gender roles, and conceptions of freedom.

Introduction

The United States in 1900

Twentieth Century Revolutions

The Progressive Era

Progressivism is an umbrella label for a wide range of economic, political, social, and moral reforms. These included efforts to outlaw the sale of alcohol; regulate child labor and sweatshops; scientifically manage natural resources; insure pure and wholesome water and milk; Americanize immigrants or restrict immigration altogether; and bust or regulate trusts. Drawing support from the urban, college-educated middle class, Progressive reformers sought to eliminate corruption in government, regulate business practices, address health hazards, improve working conditions, and give the public more direct control over government through direct primaries to nominate candidates for public office, direct election of Senators, the initiative, referendum, and recall, and women's suffrage.By the beginning of the twentieth century, muckraking journalists were calling attention to the exploitation of child labor, corruption in city governments, the horror of lynching, and the ruthless business practices employed by businessmen like John D. Rockefeller. At the local level, many Progressives sought to suppress red-light districts, expand high schools, construct playgrounds, and replace corrupt urban political machines with more efficient system of municipal government. At the state level, Progressives enacted minimum wage laws for women workers, instituted industrial accident insurance, restricted child labor, and improved factory regulation.

At the national level, Congress passed laws establishing federal regulation of the meat-packing, drug, and railroad industries, and strengthened anti-trust laws. It also lowered the tariff, established federal control over the banking system, and enacted legislation to improve working condition. Four constitutional amendments were adopted during the Progressive era, which authorized an income tax, provided for the direct election of senators, extended the vote to women, and prohibited the manufacture and sale of alcoholic beverages.

Jane Addams: Champion for the Working Poor

Progressivism

A New Era

The Roots of Progressivism

Herbert Croly and The Promise of American Life

Newsies

Municipal Progressivism

State Progressivism

National Progressivism

Theodore Roosevelt

Anti-Trust

Government Regulation

Conservation

Taft

Income Tax

Wilson

Along the Color Line

The period late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries represented the nadir of American race relations. Nine-tenths of African Americans lived in the South, and most supported themselves as tenant farmers or sharecroppers. Most southern and border states instituted a legal system of segregation, relegating African Americans to separate schools and other public accommodations. Under the Mississippi Plan, involving the use of poll taxes and literacy tests, African Americans were deprived of the vote. The Supreme Court stripped the 14th and 15th Amendments of their meaning, especially in the 1896 case of Plessy v. Ferguson, which declared that “separate but equal” facilities were permissible under the 14th Amendment. Each year approximately a hundred African Americans were lynched.Booker T. Washington, the most prominent black leader, argued that African Americans should make themselves economically indispensable to southern whites, cooperate with whites, and accommodate themselves to white supremacy. But other figures adopted a more activist stance, such as the anti-lynching crusader Ida B. Wells, and W.E.B. DuBois, a founder of the NAACP, who demanded an end to caste distinctions based on race.

A tight labor market during World War I triggered the “Great Migration” of African Americans to the North, which continued into the 1920s. But the movement of blacks out of the South was met by racial violence in Chicago, East St. Louis, Houston, Tulsa, and other cities.

The Great Migration was accompanied by new efforts at black political and economic organization and cultural expression, including Marcus Garvey's Universal Negro Improvement Association, which emphasized racial pride and economic self-help, and the Harlem Renaissance, a literary and artistic movement.

The State of African Americans in the South

Lynching

Convict Lease System

Jim Crow and the Courts

Plessy v. Ferguson

Segregation and Disfranchisement

Booker T. Washington and the Politics of Accommodation

Conclusion

The Struggle for Women's Suffrage

Among the most radical of all struggles in American history is the on-going struggle of women for full equality. The ideals of the American Revolution raised women's expectations, inspired some of the first explicit demands for equality, and witnessed the establishment of female academies to improve women's education. By the early 19th century, American women had the highest female literacy rate in the world.But as American states widened suffrage to include virtually all white males, they began denying the vote to free blacks and, in New Jersey, to women, who had briefly won this privilege following the Revolution. In the 1820s and for decades to come married women could not own property, make contracts, bring suits, or sit on juries. They could be legally beaten by their husbands and were required to submit to their husbands' sexual demands.

During the early 19th century, however, a growing number of women became convinced that they had a special mission and responsibility to purify and reform American society. Women were at the forefront of efforts to establish public schools, abolish slavery, and curb drinking. But faced with discrimination within the antislavery movement, Elizabeth Cady Stanton and others organized the first Women's Rights Convention in history in Seneca Falls, New York, in 1848.

The quest for full equality involved not only the struggle for the vote, but for divorce, access to higher education, the professions, and other occupations, as well as birth control and abortion. Women have had to overcome laws and customs that discriminated on the basis of sex in order to overcome the oldest form of exploitation and subordination.

"Failure is Impossible"

72 Years

The Drive for the Vote Begins

The Movement Splits

The First Breakthroughs

New Arguments and New Constituencies

Opponents of Suffrage

The Final Push

Did the Vote Make a Difference?

Political Firsts

Birth Control

United States Becomes a World Power

This chapter examines the reasons why the United States adopted a more aggressive foreign policy at the end of the 19th century; the causes, military history, and consequences of the Spanish American War; and early 20th century U.S. involvement in China, the Caribbean, and Latin America.

"A Man, A Plan, A Canal, Panama"

The United States Becomes a World Power

The Annexation of Hawaii

The Spanish American War

The Philippines

Policing the Caribbean and Central America

Intervention in Haiti

America at War: World War I

This chapter examines the war’s causes, the reasons why the United States intervened in the conflict, how American industry was mobilized for war, wartime propaganda and political repression, and the social changes and unrest produced by the war.

Sgt. York

World War I

The Road to War

The Guns of August

The Lusitania

The United States Enters the War:

Over There: American Doughboys Go to War

Over Here: World War I on the Home Front

The Espionage and Sedition Acts