The East Indiaman Atlas made her first voyage in 1813. She was mounted with 26-guns and had a complement of 130 men at full strength. East Indiaman was a general name for any sailing ship belonging to the Austrian, Danish, Dutch, English, French, Portuguese, or Swedish East India trading companies.

The gradual emergence of new economic structures that made European global influence possible both presupposed and promoted far-reaching changes in human capital, property rights, financial instruments, technologies, and labor systems.

Commerce,

c. 1648-1815 CE

Contents

The economic watershed of the 17th and 18th centuries was a historically unique passage from limited resources that made material want inescapable to self-generating economic growth that dramatically raised levels of physical and material well-being. European societies—first those with access to the Atlantic and gradually those to the east and on the Mediterranean—provided increasing percentages of their populations with a higher standard of living.

The gradual emergence of new economic structures that made European global influence possible both presupposed and promoted far-reaching changes in human capital, property rights, financial instruments, technologies, and labor systems. These changes included an availability of labor power, both in terms of numbers and in terms of persons with the skills (literacy, ability to understand and manipulate the natural world, physical health sufficient for work) required for efficient production along with institutions and practices that supported economic activity and provided incentives for it (new definitions of property rights and protections for them against theft or confiscation and against state taxation).

Accumulations of capital for financing enterprises and innovations, as well as for raising the standard of living and the means for turning private savings into investable or “venture” capital. Technological innovations in food production, transportation, communication, and manufacturing. A major result of these changes was the development of a growing consumer society that benefited from and contributed to the increase in material resources. At the same time, other effects of the economic revolution—including increased geographic mobility, transformed employer–worker relations, the decline of domestic manufacturing—eroded traditional community and family solidarities and protections.

European economic strength derived in part from the ability to control and exploit resources (human and material) around the globe. Mercantilism supported the development of European trade and influence around the world, which, in turn, encouraged overseas exploration, expansion, and conflicts. Internally, Europe divided more and more sharply between the societies engaging in overseas trade and undergoing the economic transformations sketched above (primarily countries on the Atlantic) and those (primarily in central and eastern Europe) with little such involvement. The eastern European countries remained in a traditional, principally agrarian, economy and maintained the traditional order of society and the state that rested on it.

Source: https://apcentral.collegeboard.org/pdf/ap-european-history-course-and-exam-description.pdf

The gradual emergence of new economic structures that made European global influence possible both presupposed and promoted far-reaching changes in human capital, property rights, financial instruments, technologies, and labor systems. These changes included an availability of labor power, both in terms of numbers and in terms of persons with the skills (literacy, ability to understand and manipulate the natural world, physical health sufficient for work) required for efficient production along with institutions and practices that supported economic activity and provided incentives for it (new definitions of property rights and protections for them against theft or confiscation and against state taxation).

Accumulations of capital for financing enterprises and innovations, as well as for raising the standard of living and the means for turning private savings into investable or “venture” capital. Technological innovations in food production, transportation, communication, and manufacturing. A major result of these changes was the development of a growing consumer society that benefited from and contributed to the increase in material resources. At the same time, other effects of the economic revolution—including increased geographic mobility, transformed employer–worker relations, the decline of domestic manufacturing—eroded traditional community and family solidarities and protections.

European economic strength derived in part from the ability to control and exploit resources (human and material) around the globe. Mercantilism supported the development of European trade and influence around the world, which, in turn, encouraged overseas exploration, expansion, and conflicts. Internally, Europe divided more and more sharply between the societies engaging in overseas trade and undergoing the economic transformations sketched above (primarily countries on the Atlantic) and those (primarily in central and eastern Europe) with little such involvement. The eastern European countries remained in a traditional, principally agrarian, economy and maintained the traditional order of society and the state that rested on it.

Source: https://apcentral.collegeboard.org/pdf/ap-european-history-course-and-exam-description.pdf

By the end of the 18th century, it was evident that a high proportion of Europeans were better fed, healthier, longer lived, and more secure and comfortable in their material well-being than at any previous time in human history.

The legacies of the 16th-century population explosion, which roughly doubled the European population, were social disruptions and demographic disasters that persisted into the 18th century. Volatile weather in the 17th century harmed agricultural production. In some localities, recurring food shortages caused undernourishment that combined with disease to produce periodic spikes in mortality. By the 17th century, the European marriage pattern, which limited family size, became the most important check on population levels, although some couples also adopted birth control practices to limit family size.

By the middle of the 18th century, better weather, improvements in transportation, new crops and agricultural practices, less epidemic disease, and advances in medicine and hygiene allowed much of Europe to escape from the cycle of famines that had caused repeated demographic disaster. By the end of the 18th century, reductions in child mortality and increases in life expectancy constituted the demographic underpinnings of new attitudes toward children and families. Particularly in western Europe, the demographic revolution, along with the rise in prosperity, produced advances in material well-being that did not stop with the economic: greater prosperity was associated with increasing literacy, education, and rich cultural lives (the growth of publishing and libraries, the founding of schools, and the establishment of orchestras, theaters, and museums).

By the end of the 18th century, it was evident that a high proportion of Europeans were better fed, healthier, longer lived, and more secure and comfortable in their material well-being than at any previous time in human history. This relative prosperity was balanced by increasing numbers of the poor throughout Europe, who strained charitable resources and alarmed government officials and local communities.

Source: https://apcentral.collegeboard.org/pdf/ap-european-history-course-and-exam-description.pdf

By the middle of the 18th century, better weather, improvements in transportation, new crops and agricultural practices, less epidemic disease, and advances in medicine and hygiene allowed much of Europe to escape from the cycle of famines that had caused repeated demographic disaster. By the end of the 18th century, reductions in child mortality and increases in life expectancy constituted the demographic underpinnings of new attitudes toward children and families. Particularly in western Europe, the demographic revolution, along with the rise in prosperity, produced advances in material well-being that did not stop with the economic: greater prosperity was associated with increasing literacy, education, and rich cultural lives (the growth of publishing and libraries, the founding of schools, and the establishment of orchestras, theaters, and museums).

By the end of the 18th century, it was evident that a high proportion of Europeans were better fed, healthier, longer lived, and more secure and comfortable in their material well-being than at any previous time in human history. This relative prosperity was balanced by increasing numbers of the poor throughout Europe, who strained charitable resources and alarmed government officials and local communities.

Source: https://apcentral.collegeboard.org/pdf/ap-european-history-course-and-exam-description.pdf

18th Century Society

Objective: Explain the factors contributing to and the consequences of demographic changes from 1648 to 1815.

18th Century Social Structure

Empress Maria Theresa of Austria gave birth to 16 children, including Queen Marie Antoinette of France and Emperor Joseph II of Austria.

- The experiences of everyday life were shaped by demographic, environmental, medical, and technological changes.

- By the 18th century, family and private life reflected new demographic patterns and the effects of the commercial revolution.

|

The transgender Chevalier D’Eon, who worked for French King Louis XV as a spy in London, became a minor society celebrity. They presented as a man and a woman at various points in their life, until aged about 50 they began to live permanently as a woman.

|

French commoners are burdened by the weight of the clergy and nobility in the pre-revolutionary Ancien Regime.

|

18th Century Urban Life

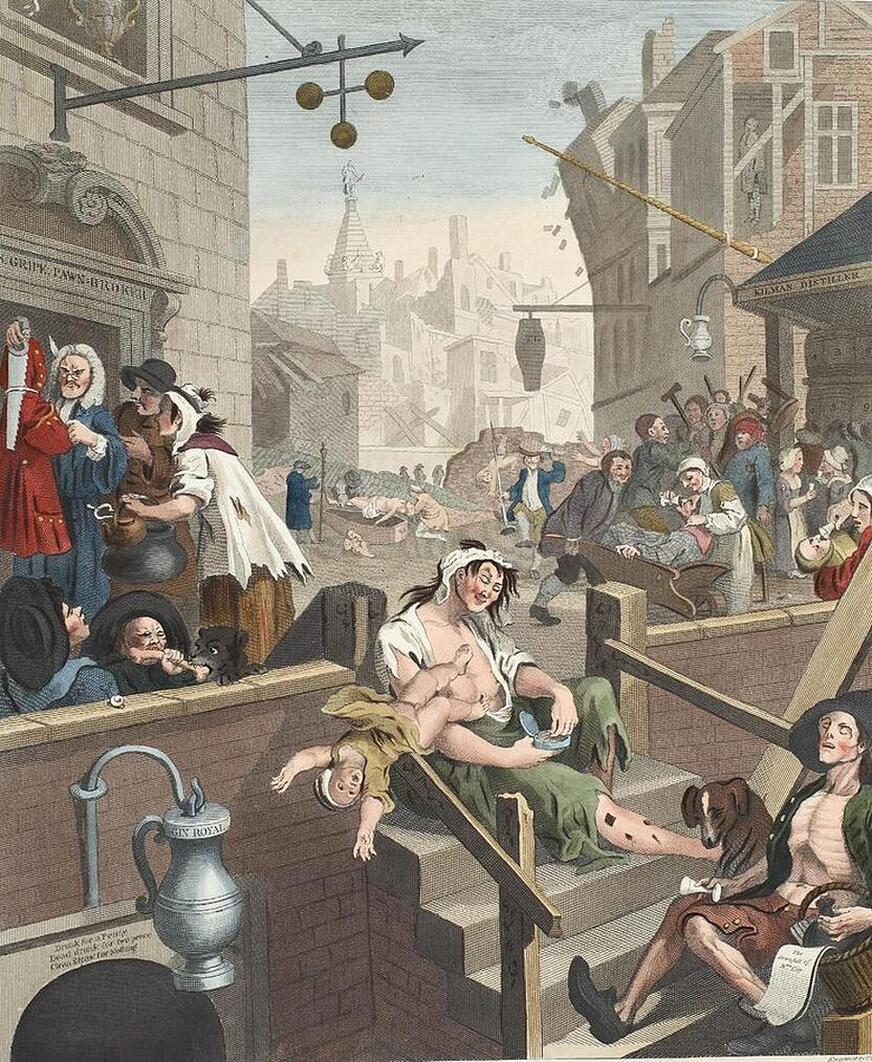

Gin Lane (1751) by William Hogarth depicts the squalor and despair of a community raised on gin showing shocking scenes of infanticide, starvation, madness, decay and suicide. The mother in the foreground, addled by gin and driven to prostitution (as evidenced by the syphilitic sores on her legs) lets her baby slip from her arms and plunge to its death. This was not such an exaggeration: in 1734, Judith Dufour reclaimed her two-year-old child from the workhouse where it had been given a new set of clothes; she then strangled it and left the infant's body in a ditch so that she could sell the clothes to buy gin.

- The Agricultural Revolution produced more food using fewer workers; as a result, people migrated from rural areas to the cities in search of work.

- The growth of cities eroded traditional communal values, and city governments strained to provide protection and a healthy environment.

- Cities offered economic opportunities, which attracted increasing migration from rural areas, transforming urban life and creating challenges for the new urbanites and their families.

- Although the rate of illegitimate births increased in the 18th century, population growth was limited by the European marriage pattern, and in some areas by various birth control methods.

- As infant and child mortality decreased, and commercial wealth increased, families dedicated more space and resources to children and child-rearing, as well as private life and comfort.

The Great Lisbon earthquake of 1755, the largest natural catastrophe ever recorded in Europe, killed an estimated 30,000-50,000 people. Occurring on All Saints' Day, a major Catholic religious holiday, it was interpreted as divine punishment by many and led to questioning of religion by philosophes during the Enlightenment.

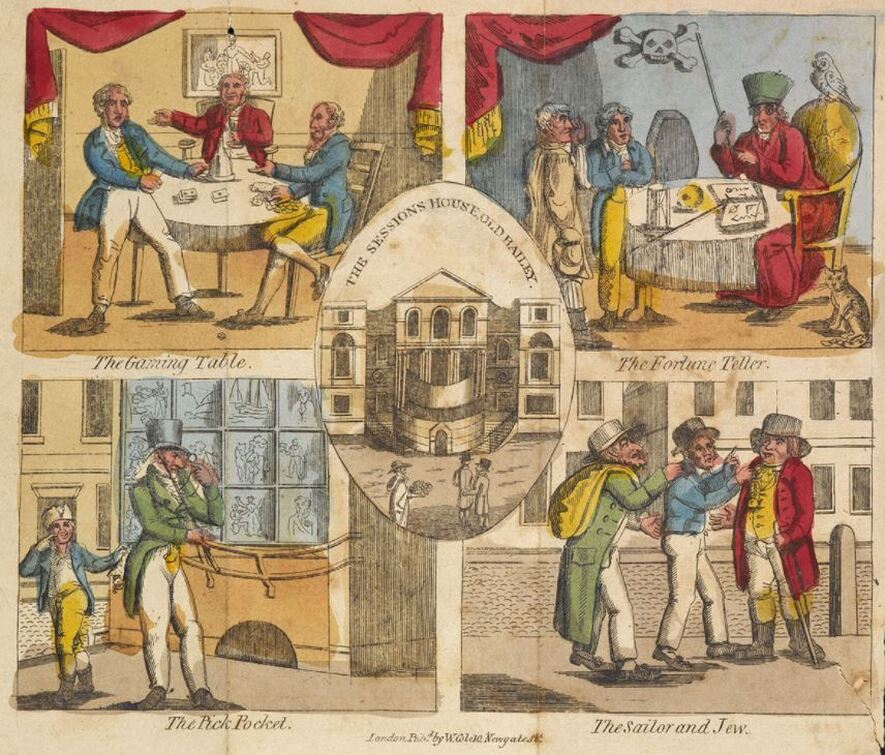

18th Century Crime and Punishment

The Frauds of London - the Gaming Table, the Fortune Teller, the Pick Pocket, the Sailor and Jew

- The concentration of the poor in cities led to a greater awareness of poverty, crime, and prostitution as social problems, and prompted increased efforts to police marginal groups.

|

18th Century Society (comprehensive)

18th Century Society (abridged)

|

Agricultural Revolution and Proto-Industrialization

Objective: Explain the continuities and changes in commercial and economic developments from 1648 to 1815.

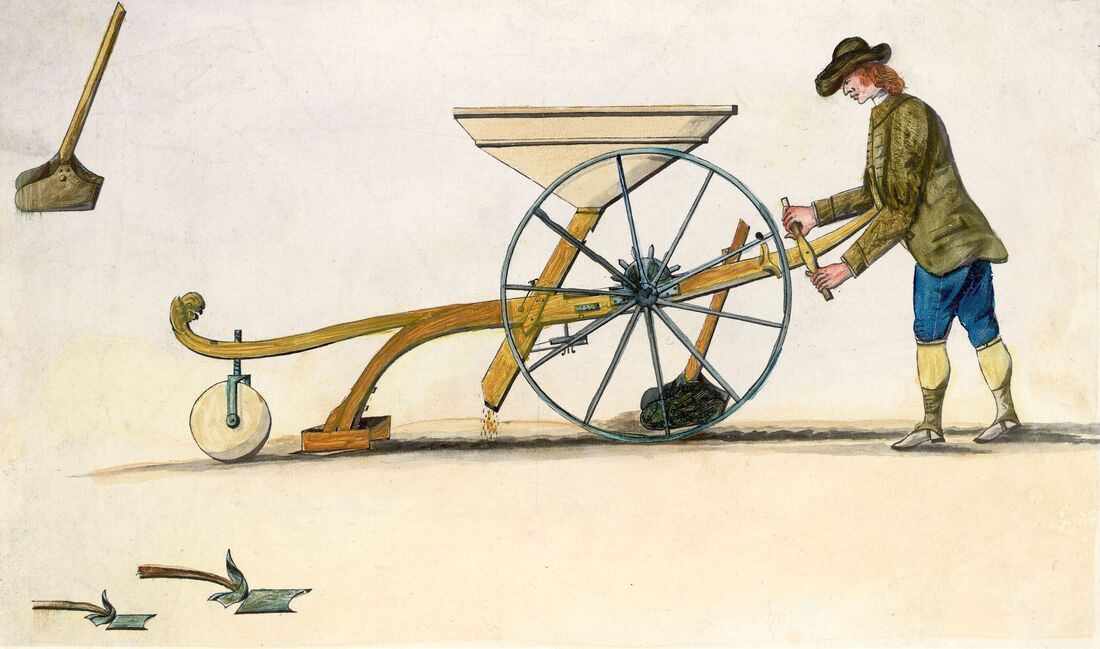

Jethro Tull's seed drill

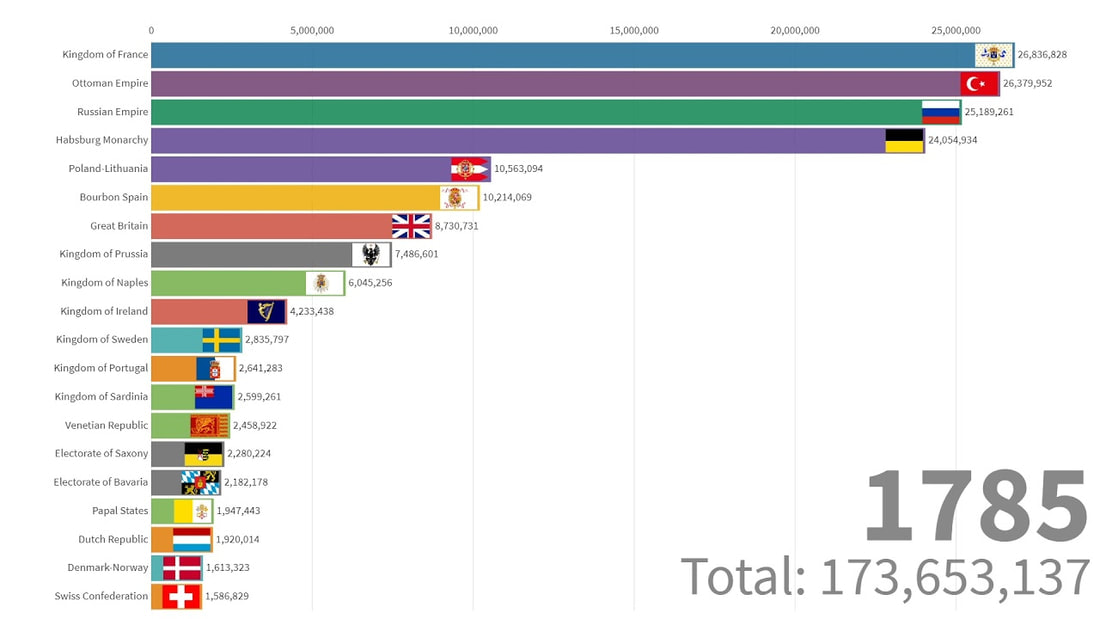

European population in 1785

|

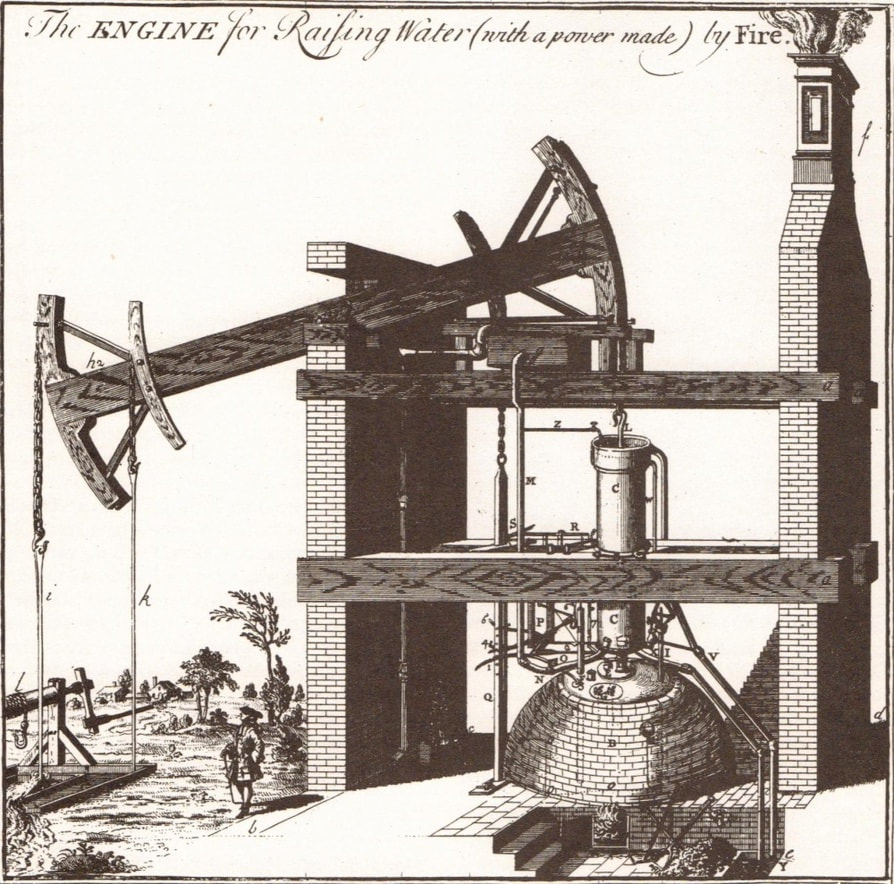

Thomas Newcomen built the first steam engine in 1712 to pump water out of deep mine shafts.

|

|

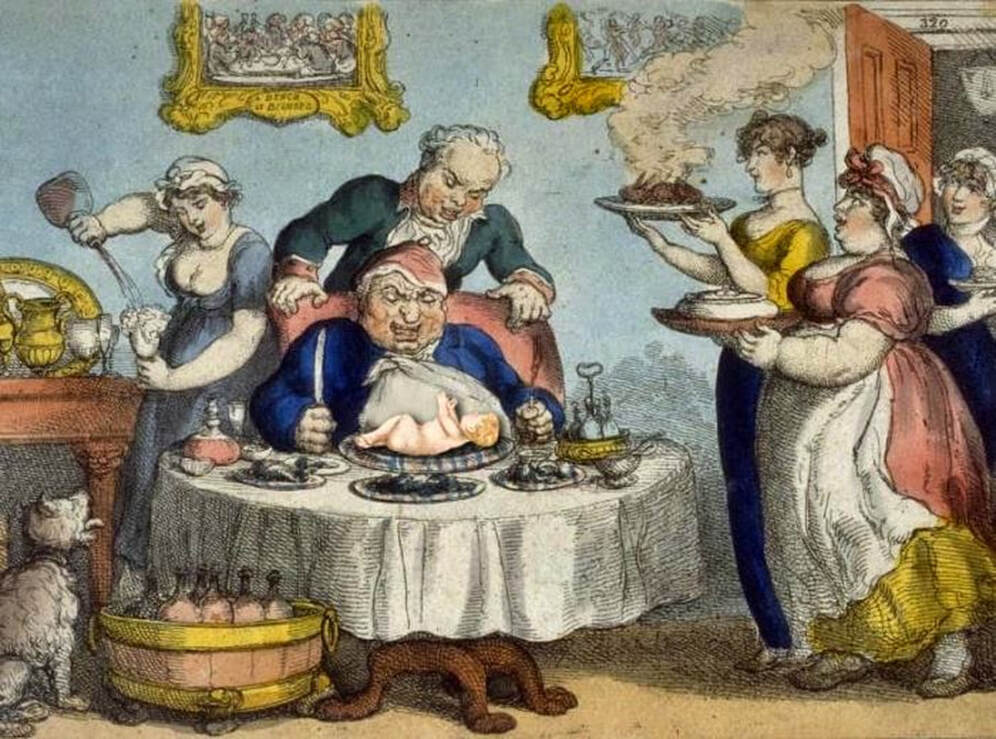

"I have been assured ... that a young healthy child well nursed is, at a year old, a most delicious nourishing and wholesome food, whether stewed, roasted, baked, or boiled ..."

In the satire A Modest Proposal (1729), Jonathan Swift suggests that the poverty-stricken in overpopulated Ireland sell their children as food for rich gentlemen and ladies.

In the satire A Modest Proposal (1729), Jonathan Swift suggests that the poverty-stricken in overpopulated Ireland sell their children as food for rich gentlemen and ladies.

Markets

Objectives:

- Explain the continuities and changes in commercial and economic developments from 1648 to 1815.

- Explain the factors contributing to and the consequences of demographic changes from 1648 to 1815.

- Explain the causes and consequences of European maritime competition from 1648 to 1815.

Property

|

The English Navigation Acts required English colonies to trade only with England making London rich but sparking the Anglo-Dutch Wars and contributing to the American Revolution.

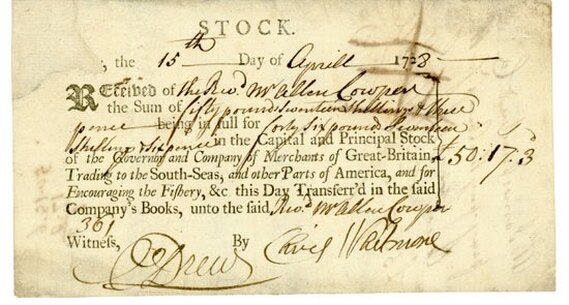

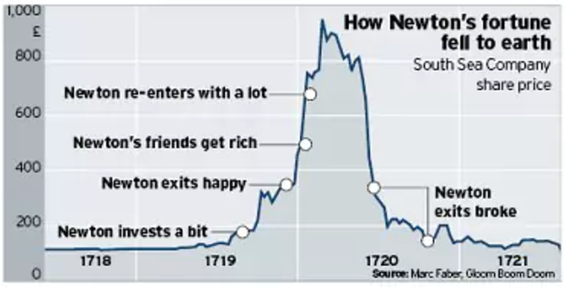

South Sea Company stock certificate, 1728

Isaac Newton was a victim of the South Sea Bubble. He invested early then sold after making excellent returns quickly. He then re-entered the market close to the peak, and hung on even after the bubble burst losing £20,000, (about £3m today).

|

|

|

Agricultural Revolution, Proto-Industrialization, and Markets (comprehensive)

Agricultural Revolution, Proto-Industrialization, and Markets (abridged)

|

Consumerism

Pronkstilleven (Dutch for 'ostentatious', 'ornate' or 'sumptuous') still life paintings showcase the luxury goods of wealthy citizens of the Dutch Golden Age.

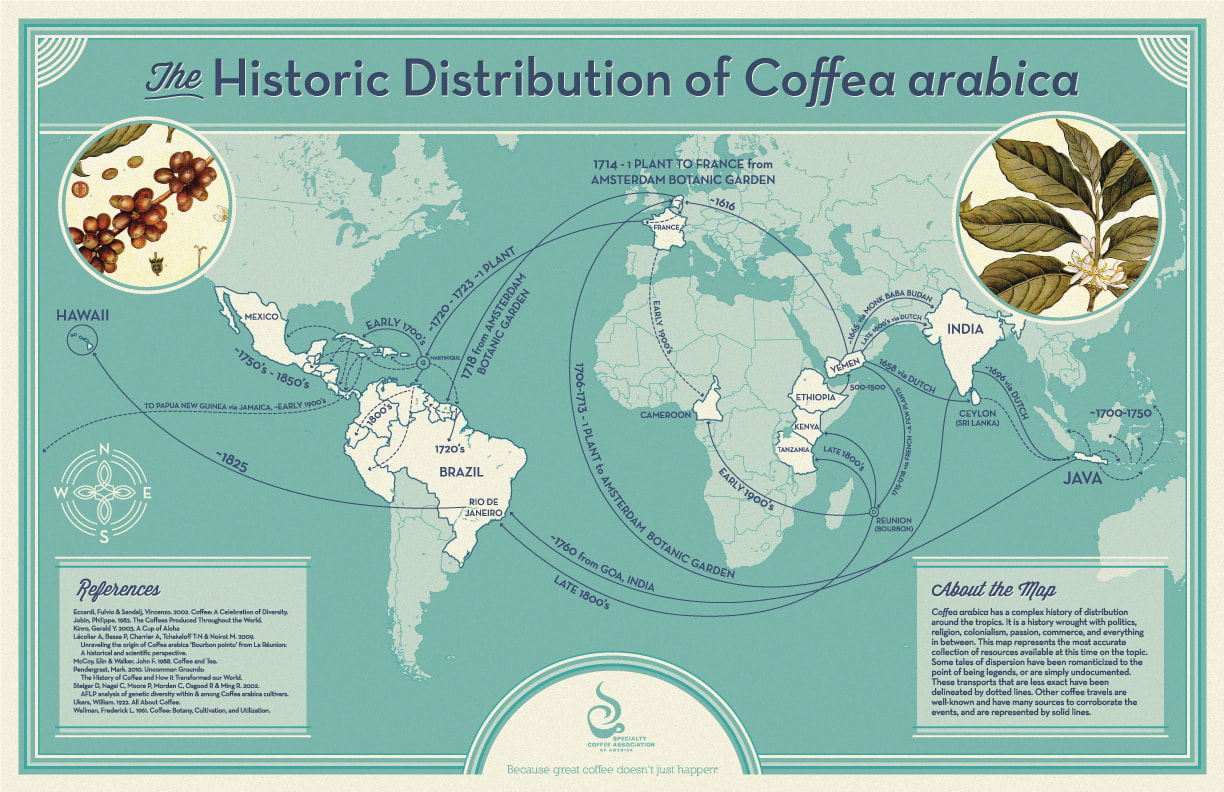

- The European-dominated worldwide economic network contributed to the agricultural, industrial, and consumer revolutions in Europe.

- Overseas products and influences contributed to the development of a consumer culture in Europe.

- The consumer revolution of the 18th century was shaped by a new concern for privacy, encouraged the purchase of new goods for homes, and created new venues for leisure activities.

|

bridge and Parthenon at Stourhead estate in England

The widespread construction of Palladian estates was a symbol of England's growing prosperity during the 1600s and 1700s.

|

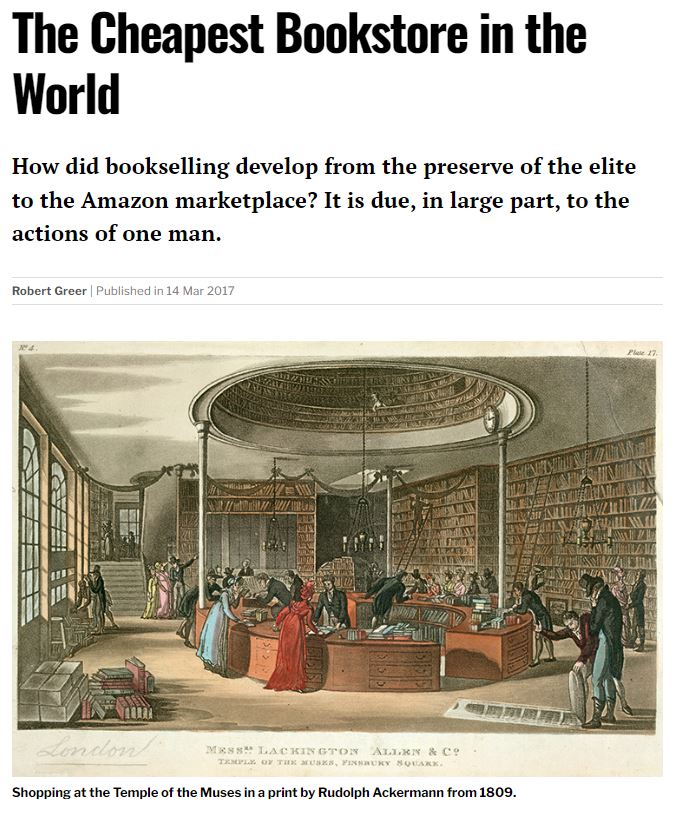

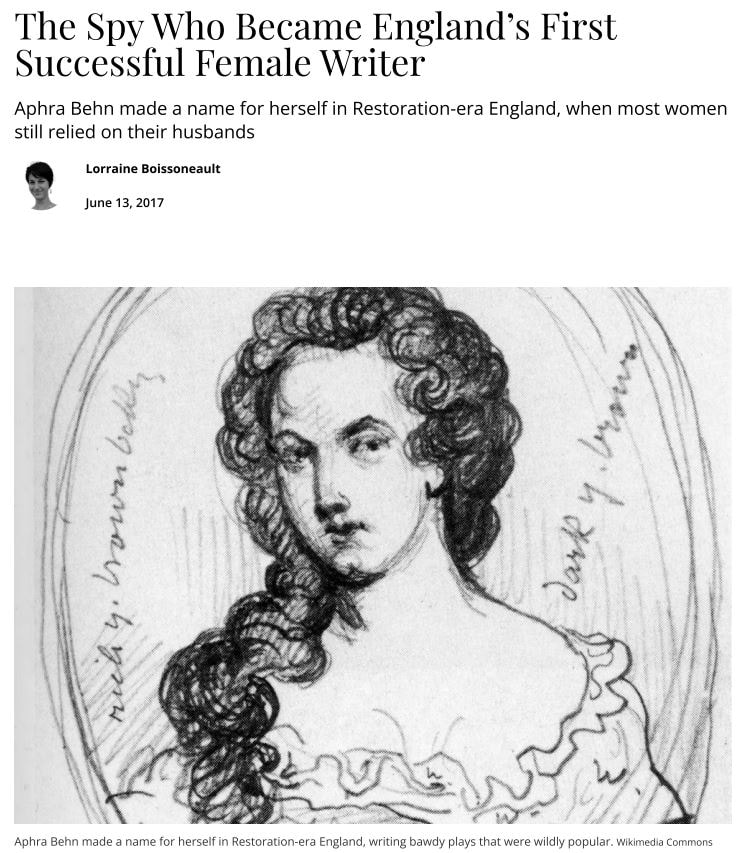

Article: The Cheapest Bookstore in the World

|

visualization of Teatro San Cassiano in Venice, the world's first public opera house which opened in 1637

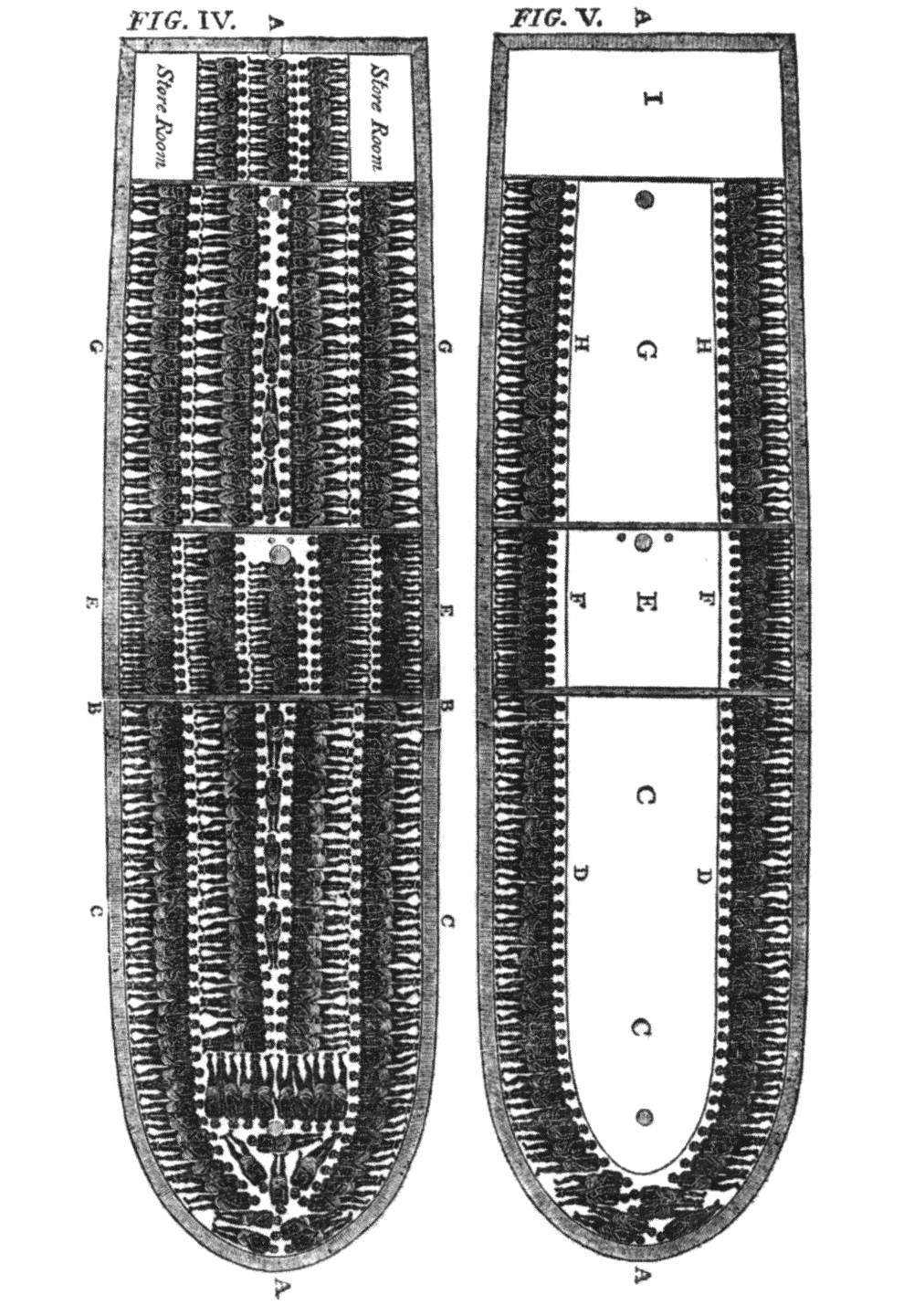

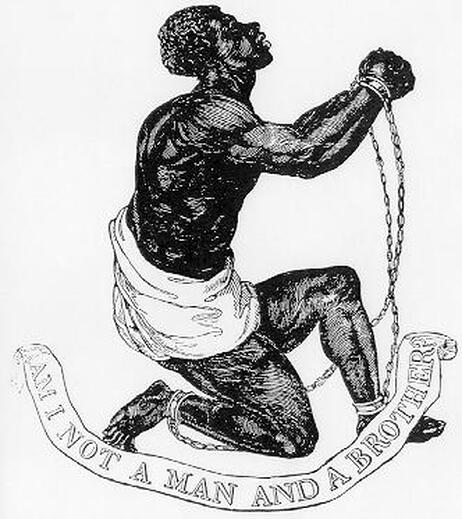

Slavery

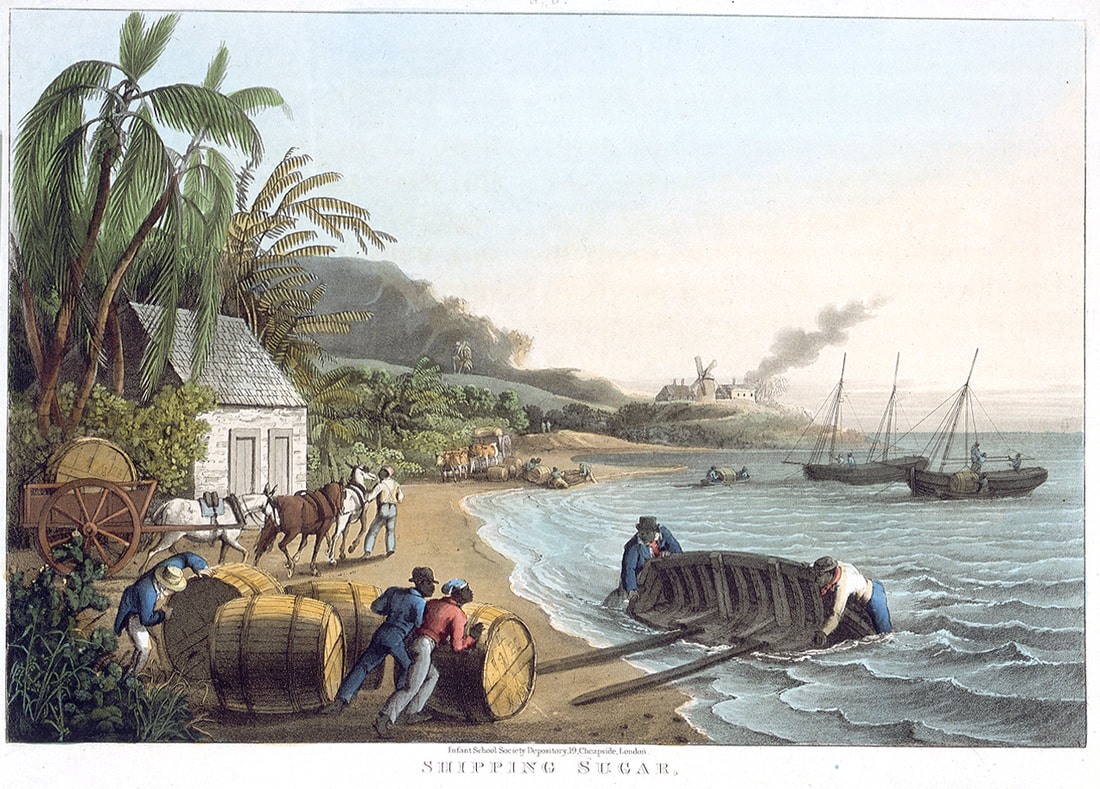

enslaved people producing sugar in Antigua, 1823

‘Interior of a boiling house in Antigua’ by William Clark (1823) shows an idealised version of what work was like on a sugar plantation. None of the everyday hardships or violence of slavery are shown.

|

"Am I Not a Man and a Brother?" medallion created as part of anti-slavery campaign by Josiah Wedgwood, 1787

|

|

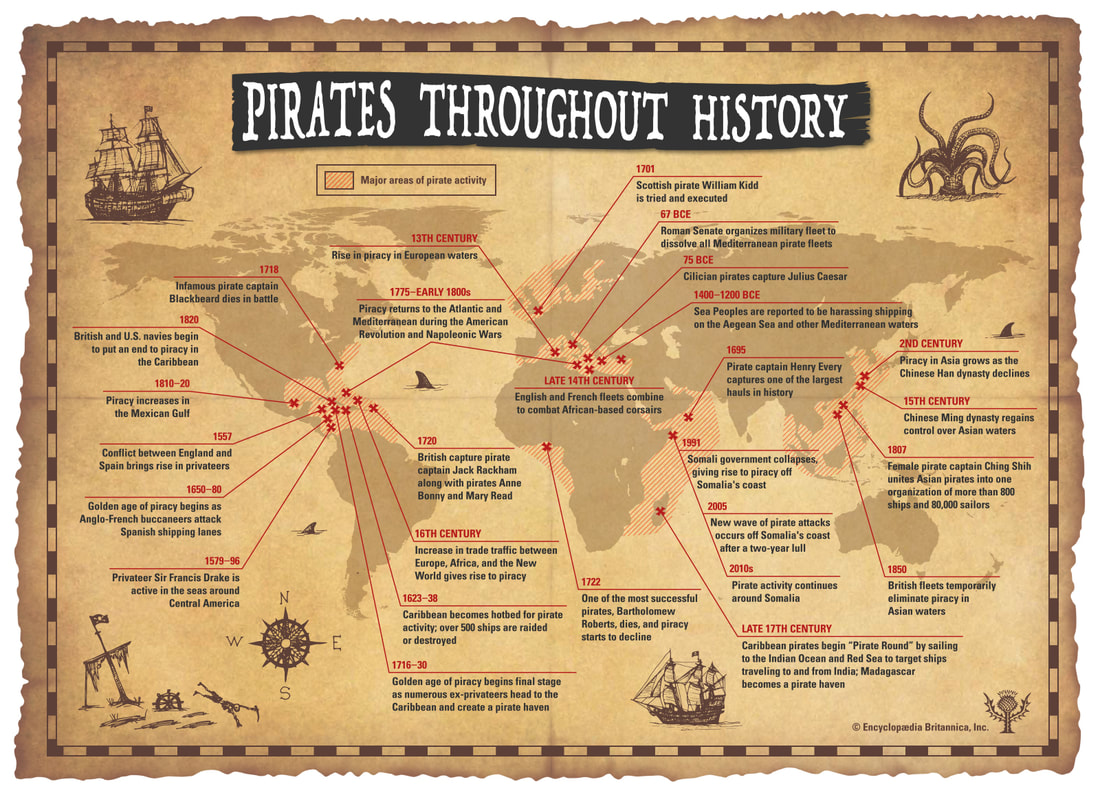

Piracy

Henry Morgan destroys the Spanish Fleet at Lake Maracaibo, 1669

|

Henry Every, the so-called "King of Pirates", was perhaps the most successful pirate of all time. He made off with the equivalent of tens of millions of dollars in today's currency when he raided ships belonging to the Mughal emperor of India in 1695.

Blackbeard (c. 1736 engraving used to illustrate Johnson's General History)

“Black Bart” Roberts capturing a fleet of eleven English, French, and Portuguese slave ships off the coast of Africa, 1722

|

|

British sailors boarding an Algerian pirate ship

|

Consumerism, Slavery, and Piracy (comprehensive)

Consumerism, Slavery, and Piracy (abridged)

|