BASF-chemical factories in Ludwigshafen, Germany, 1881

Although continental nations sought to borrow from and in some instances imitate the British model—the success of which was represented by the Crystal Palace Exhibition in 1851 -- each nation’s experience of industrialization was shaped by its own matrix of geographic, social, and political factors.

Industry,

c. 1815-1914 CE

Contents

The transition from an agricultural to an industrial economy began in Britain in the 18th century, spread to France and Germany between 1850 and 1870, and finally spread to Russia in the 1890s. The governments of those countries actively supported industrialization. In southern and eastern Europe, some pockets of industry developed, surrounded by traditional agrarian economies.

Although continental nations sought to borrow from and in some instances imitate the British model—the success of which was represented by the Crystal Palace Exhibition in 1851—each nation’s experience of industrialization was shaped by its own matrix of geographic, social, and political factors. The legacy of the revolution in France, for example, led to a more gradual adoption of mechanization in production, ensuring a more incremental industrialization than was the case in Britain. Despite the creation of a customs union in the 1830s, Germany’s lack of political unity hindered its industrial development. However, following unification in 1871, the German Empire quickly came to challenge British dominance in key industries, such as steel, coal, and chemicals.

Beginning in the 1870s, the European economy fluctuated widely because of the vagaries of financial markets. Continental states responded by assisting and protecting the development of national industry in a variety of ways, the most important being protective tariffs, military procurements, and colonial conquests. Key economic stakeholders, such as corporations and industrialists, looked to national governments to promote economic development by subsidizing ports, transportation, and new inventions; registering patents and sponsoring education; encouraging investments and enforcing contracts; and maintaining order and preventing labor strikes. In the 20th century, some national governments assumed far-reaching control over their respective economies, largely in order to contend with the challenges of war and financial crises.

Source: https://apcentral.collegeboard.org/pdf/ap-european-history-course-and-exam-description.pdf

Although continental nations sought to borrow from and in some instances imitate the British model—the success of which was represented by the Crystal Palace Exhibition in 1851—each nation’s experience of industrialization was shaped by its own matrix of geographic, social, and political factors. The legacy of the revolution in France, for example, led to a more gradual adoption of mechanization in production, ensuring a more incremental industrialization than was the case in Britain. Despite the creation of a customs union in the 1830s, Germany’s lack of political unity hindered its industrial development. However, following unification in 1871, the German Empire quickly came to challenge British dominance in key industries, such as steel, coal, and chemicals.

Beginning in the 1870s, the European economy fluctuated widely because of the vagaries of financial markets. Continental states responded by assisting and protecting the development of national industry in a variety of ways, the most important being protective tariffs, military procurements, and colonial conquests. Key economic stakeholders, such as corporations and industrialists, looked to national governments to promote economic development by subsidizing ports, transportation, and new inventions; registering patents and sponsoring education; encouraging investments and enforcing contracts; and maintaining order and preventing labor strikes. In the 20th century, some national governments assumed far-reaching control over their respective economies, largely in order to contend with the challenges of war and financial crises.

Source: https://apcentral.collegeboard.org/pdf/ap-european-history-course-and-exam-description.pdf

Overall, although inequality and poverty remained significant social problems, the quality of material life improved. For most social groups, the standard of living rose, the availability of consumer products grew, and sanitary standards, medical care, and life expectancy improved.

Industrialization promoted the development of new socioeconomic classes between 1815 and 1914. In highly industrialized areas, such as western and northern Europe, the new economy created new social divisions, leading for the first time to the development of self-conscious economic classes, especially the proletariat and the bourgeoisie. In addition, economic changes led to the rise of trade and industrial unions, benevolent associations, sport clubs, and distinctive class-based cultures of dress, speech, values, and customs.

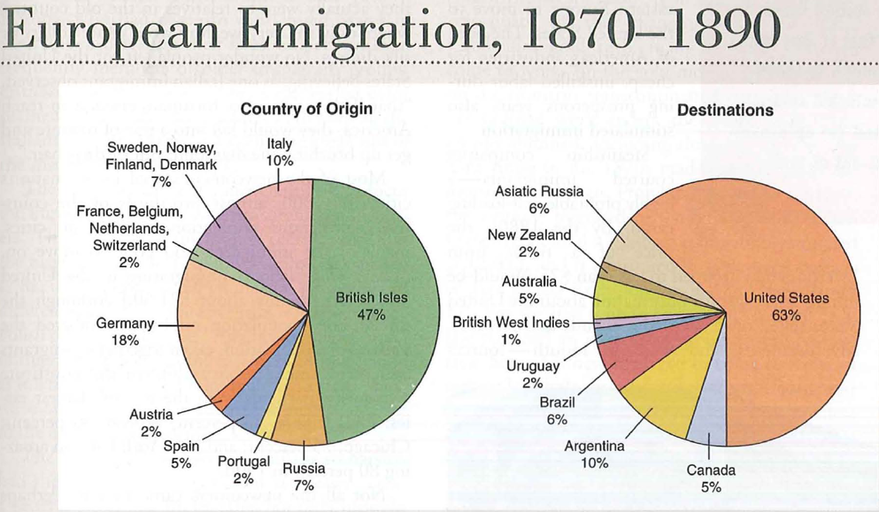

Europe also experienced rapid population growth and urbanization that resulted in benefits as well as social dislocations. The increased population created an enlarged labor force, but in some areas migration from the countryside to the towns and cities led to overcrowding and significant emigration overseas. Industrialization and urbanization changed the structure and relations of bourgeois and working-class families to varying degrees.

Birth control became increasingly common across Europe, and childhood experience changed with the advent of protective legislation, universal schooling, and smaller families. The growth of a cult of domesticity established new models of gendered behavior for men and women. Gender roles became more clearly defined as middle-class women withdrew from the workforce. At the same time, working-class women increased their participation as wage laborers, although the middle class criticized them for neglecting their families.

Industrialization and urbanization also changed people’s conception of time; in particular, work and leisure were increasingly differentiated by means of the imposition of strict work schedules and the separation of the workplace from the home. Increasingly, trade unions charged themselves as the protectors of workers and working-class families, lobbying for improved working conditions and old-age pensions. Increasing leisure time spurred the development of leisure activities and spaces for bourgeois families. Overall, although inequality and poverty remained significant social problems, the quality of material life improved. For most social groups, the standard of living rose, the availability of consumer products grew, and sanitary standards, medical care, and life expectancy improved.

Source: https://apcentral.collegeboard.org/pdf/ap-european-history-course-and-exam-description.pdf

Europe also experienced rapid population growth and urbanization that resulted in benefits as well as social dislocations. The increased population created an enlarged labor force, but in some areas migration from the countryside to the towns and cities led to overcrowding and significant emigration overseas. Industrialization and urbanization changed the structure and relations of bourgeois and working-class families to varying degrees.

Birth control became increasingly common across Europe, and childhood experience changed with the advent of protective legislation, universal schooling, and smaller families. The growth of a cult of domesticity established new models of gendered behavior for men and women. Gender roles became more clearly defined as middle-class women withdrew from the workforce. At the same time, working-class women increased their participation as wage laborers, although the middle class criticized them for neglecting their families.

Industrialization and urbanization also changed people’s conception of time; in particular, work and leisure were increasingly differentiated by means of the imposition of strict work schedules and the separation of the workplace from the home. Increasingly, trade unions charged themselves as the protectors of workers and working-class families, lobbying for improved working conditions and old-age pensions. Increasing leisure time spurred the development of leisure activities and spaces for bourgeois families. Overall, although inequality and poverty remained significant social problems, the quality of material life improved. For most social groups, the standard of living rose, the availability of consumer products grew, and sanitary standards, medical care, and life expectancy improved.

Source: https://apcentral.collegeboard.org/pdf/ap-european-history-course-and-exam-description.pdf

Industrialization

Objectives:

- Explain the factors that influenced the development of industrialization in Europe from 1815 to 1914.

- Explain how innovations and advances in technology during the Industrial Revolutions led to economic and social change.

- Explain how industrialization influenced economic and political development throughout the period from 1815 to 1914.

The Industrial Revolution: Crash Course European History #24

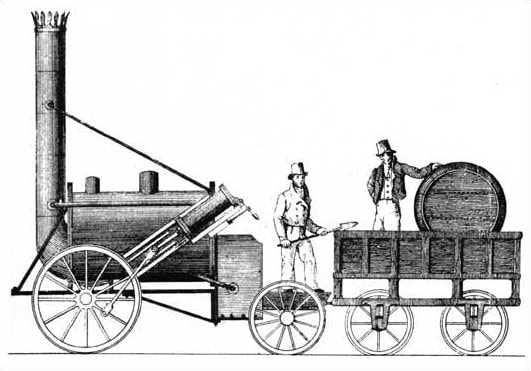

We've talked about a lot of revolutions in 19th Century Europe, and today we're moving on to a less warlike revolution, the Industrial Revolution. You'll learn about the development of steam power and mechanization, and the labor and social movements that this revolution engendered.

British

|

View from Kersal Moor towards Manchester by Thomas Pether, circa 1820, then still a rural landscape.

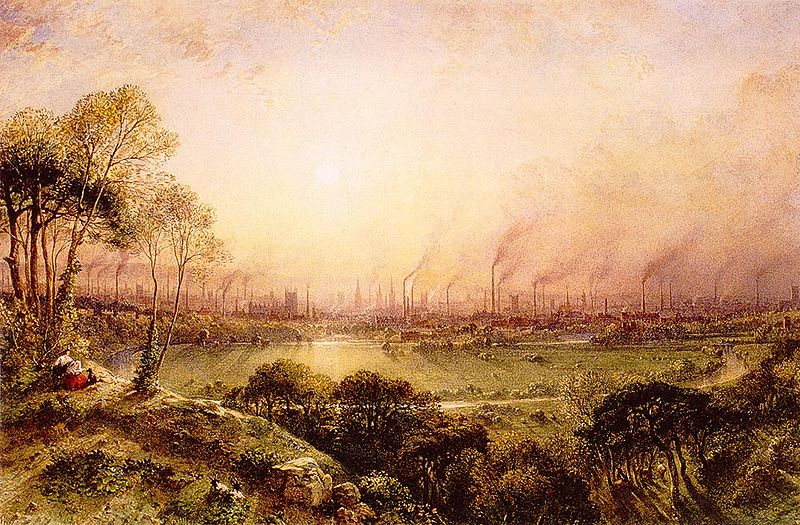

Manchester from Kersal Moor, by William Wyld in 1857, a view now dominated by chimney stacks as a consequence of the Industrial Revolution.

|

|

The first World's Fair, the Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of All Nations held at the Crystal Palace, London in 1851, housed 14,000 displays of industrial equipment from 25 countries.

Continental

|

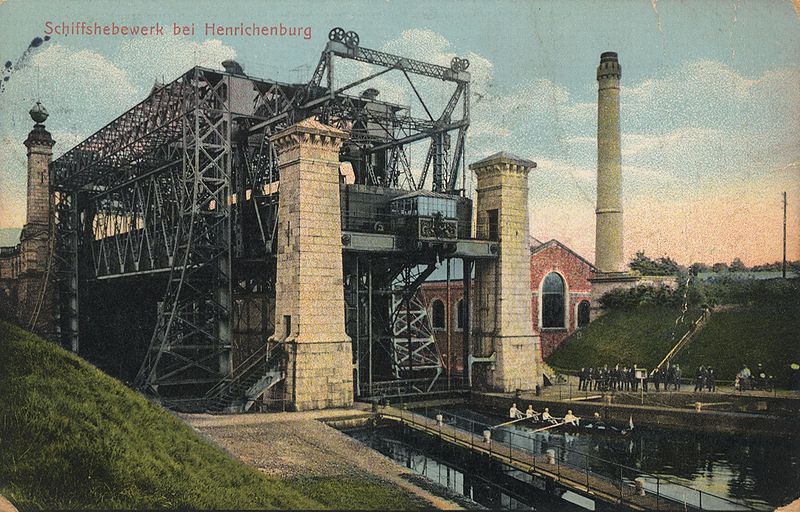

Dortmund-Ems Canal, Germany, 1912

|

|

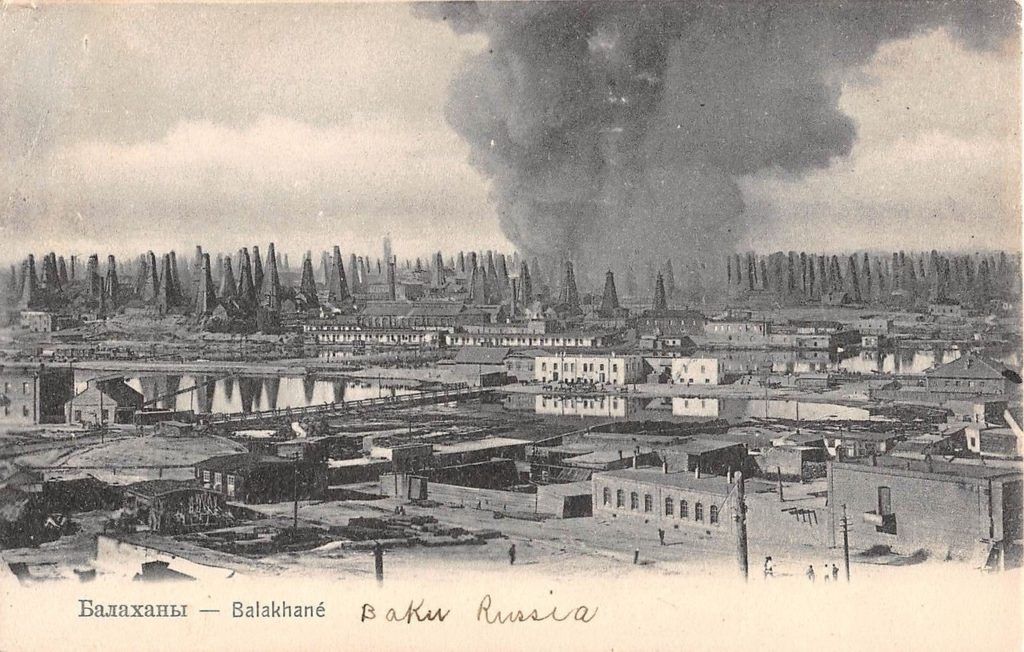

The city of Baku on the shores of the Caspian Sea was home to the world's first oil drilling. It was a major boom town at the turn of the 20th century.

|

Industrialization Quizlet (comprehensive)

Industrialization Quizlet (abridged)

|

The Second Industrial Revolution

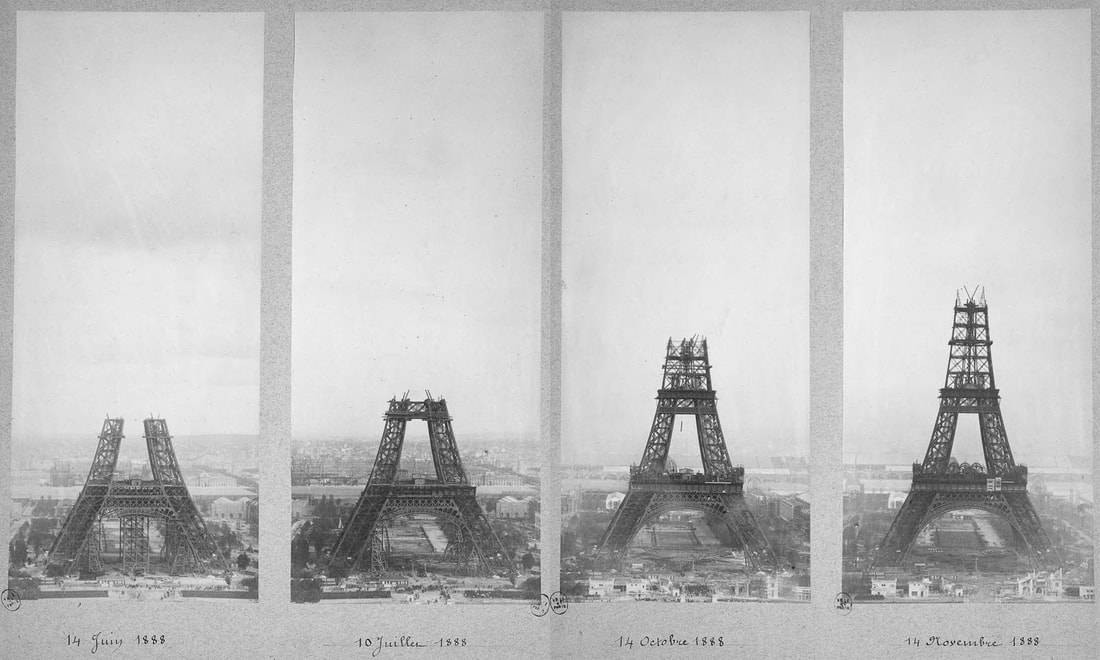

The Eiffel Tower was constructed for the Exposition Universelle world's fair of 1889.

|

In 1817, Karl Drais, a young inventor in Baden, Germany, designed and built a two-wheeled, wooden vehicle that was straddled and propelled by walking swiftly. Drais called it the laufmaschine or “running machine.” The laufmaschine soon became a novelty among Europeans, who named it the “draisine.” By 1820, the high cost of the vehicle, combined with its lack of practical value, limited its appeal and made it little more than an expensive toy. The two-wheeled vehicle would not become sustained until pedals were added in the late 1800s.

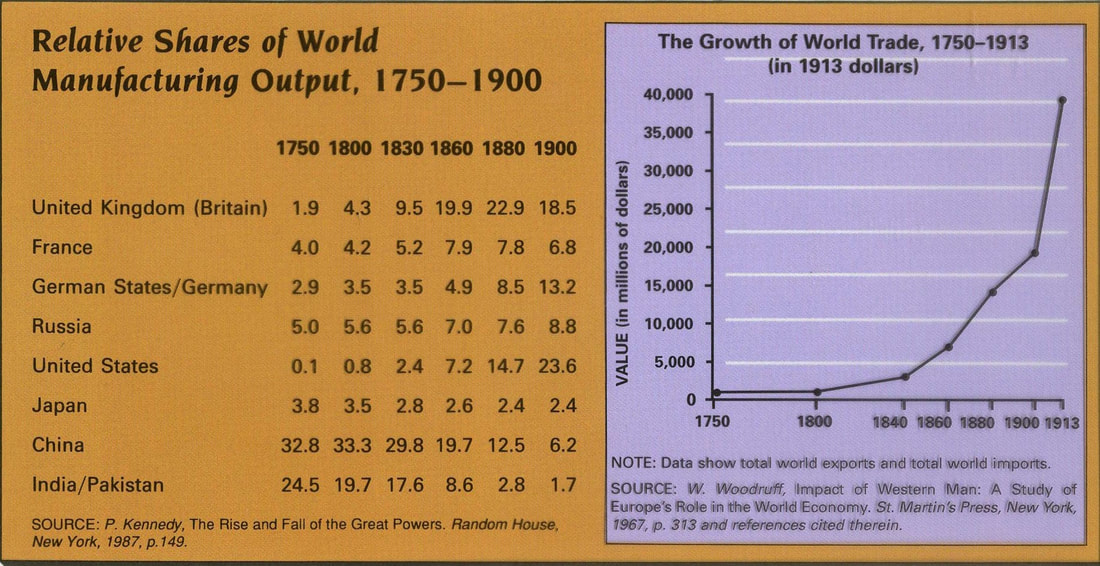

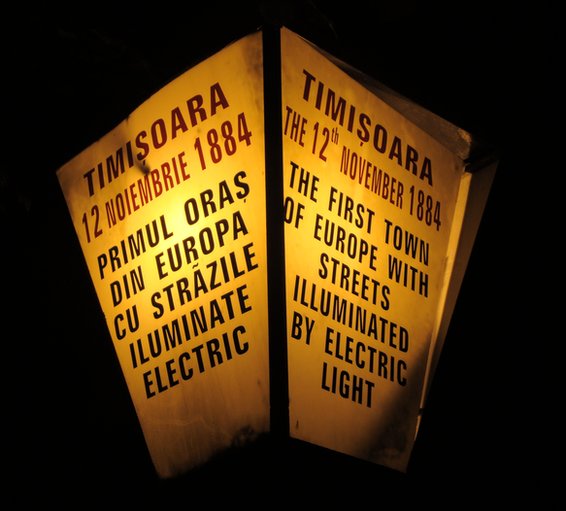

Rapid technological developments around the turn of the 20th century sped travel and communication drawing the world closer together.

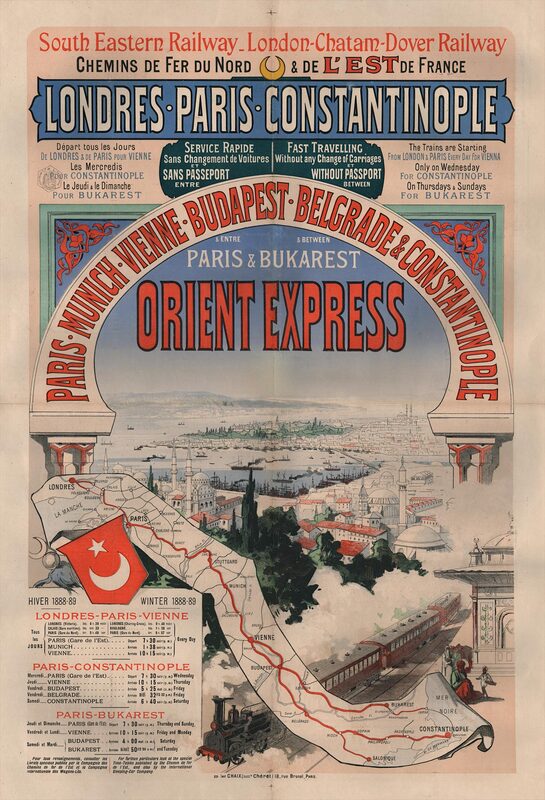

The luxurious Orient Express route opened in 1883. Passengers could travel from Paris to Istanbul by a combination of train and ferry in 80 hours.

|

|

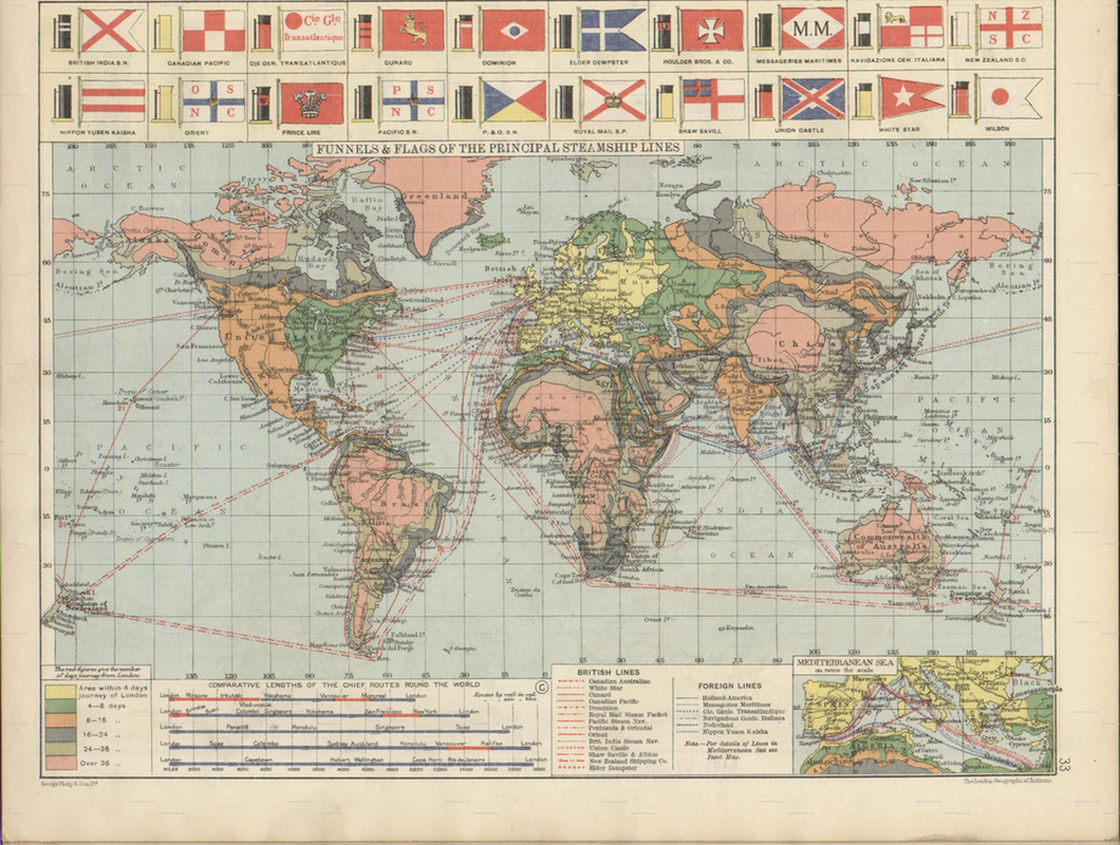

global steamship routes, c. 1920

19th Century Capitalism

traffic on the River Thames, London

|

|

The Second Industrial Revolution and 19th Century Capitalism Quizlet (comprehensive)

The Second Industrial Revolution and 19th Century Capitalism Quizlet (abridged)

|

Urbanization

Objectives:

- Explain the causes and consequences of social developments resulting from industrialization.

- Explain how and why governments and other institutions responded to challenges resulting from industrialization.

Urban Growth

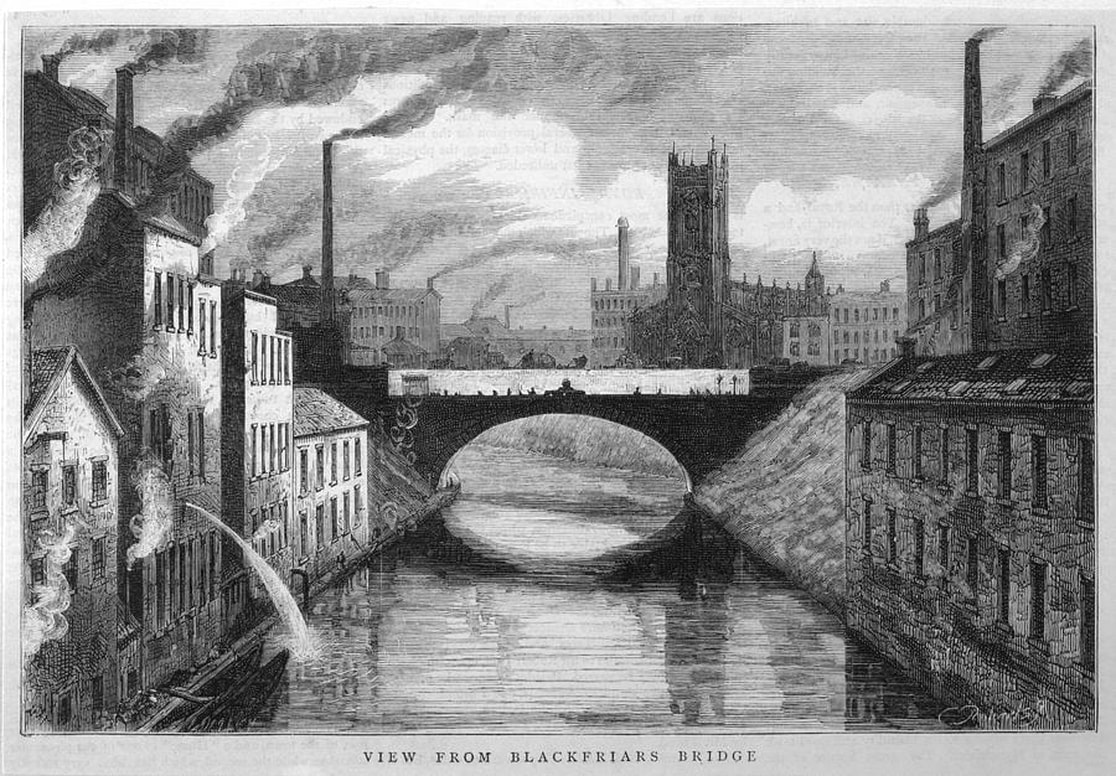

Manchester, England, c. 1844

|

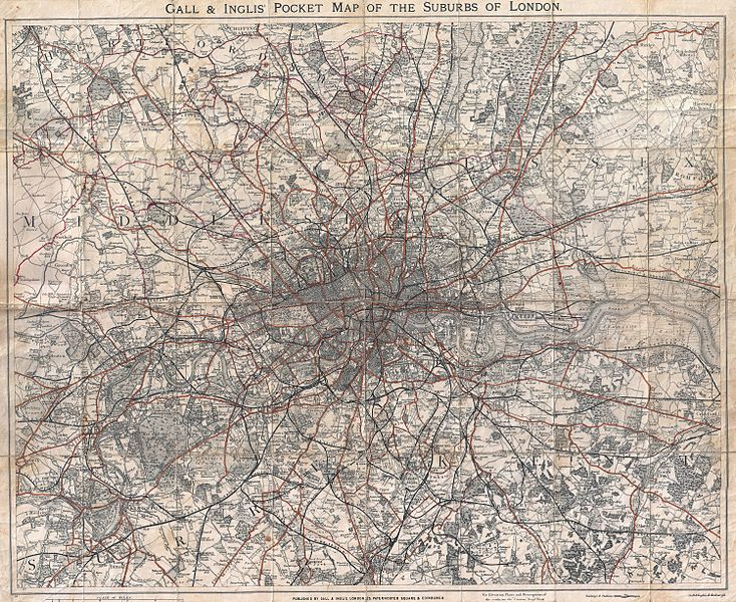

Maps of London in 1806 and 1900. London experienced tremendous growth during the 19th century.

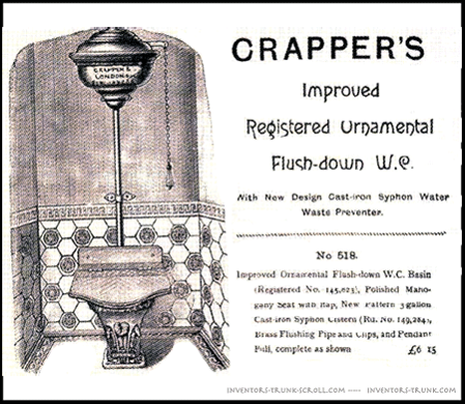

Thomas Crapper’s toilet allowed people to give a crap ... to the sewers.

|

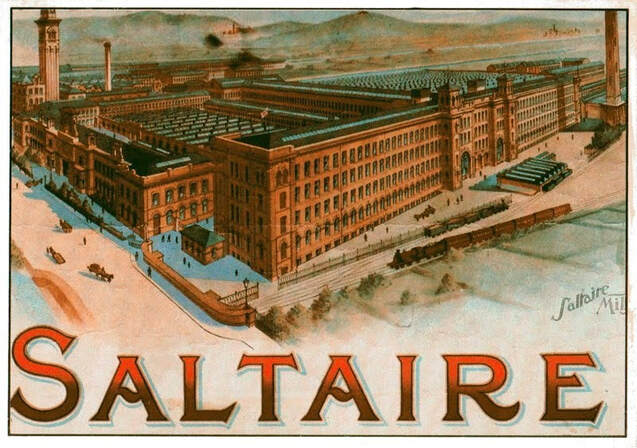

Progressive company towns like Saltaire gave industrial workers clean, healthy living accommodations.

|

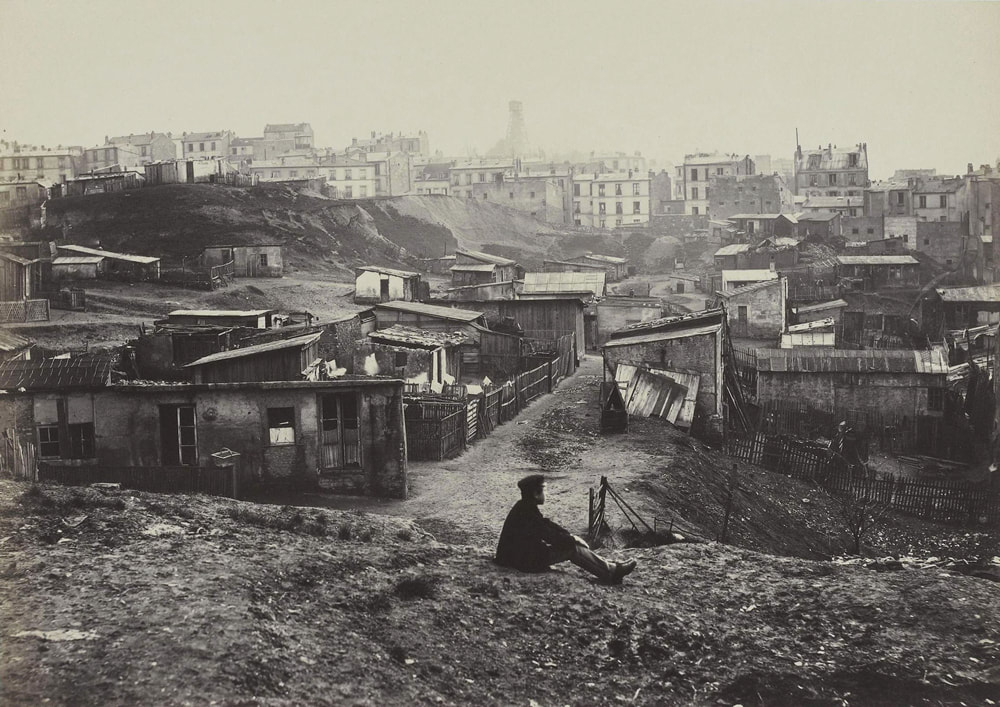

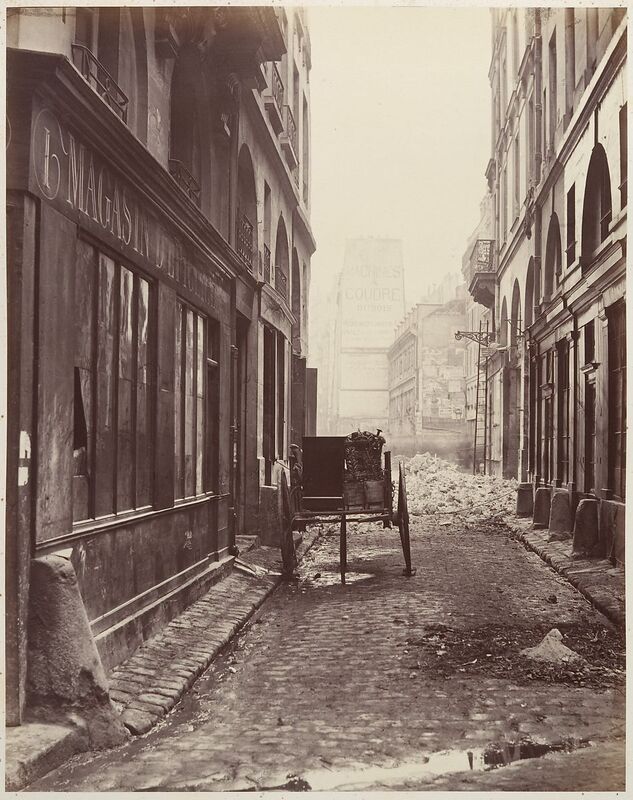

Charles Marville photographed old Paris before Georges Haussmann's extensive renovations during the reign of Napoleon III.

Haussmann demolished old slums and replaced jumbled, narrow medieval streets with long, straight avenues lined with posh buildings.

Vienna, Austria, c. 1900

|

Sarek National Park, established in Sweden in 1909, was Europe's first national park.

|

The hot springs at Széchenyi Bath, Budapest, Hungary were opened to the public in 1913.

|

Starvation and Emigration

Migration: Crash Course European History #29

Between 1840 and 1914, an estimated 40 million people left Europe. This is one of the most significant migrations in human history. So, who was leaving Europe? And why?

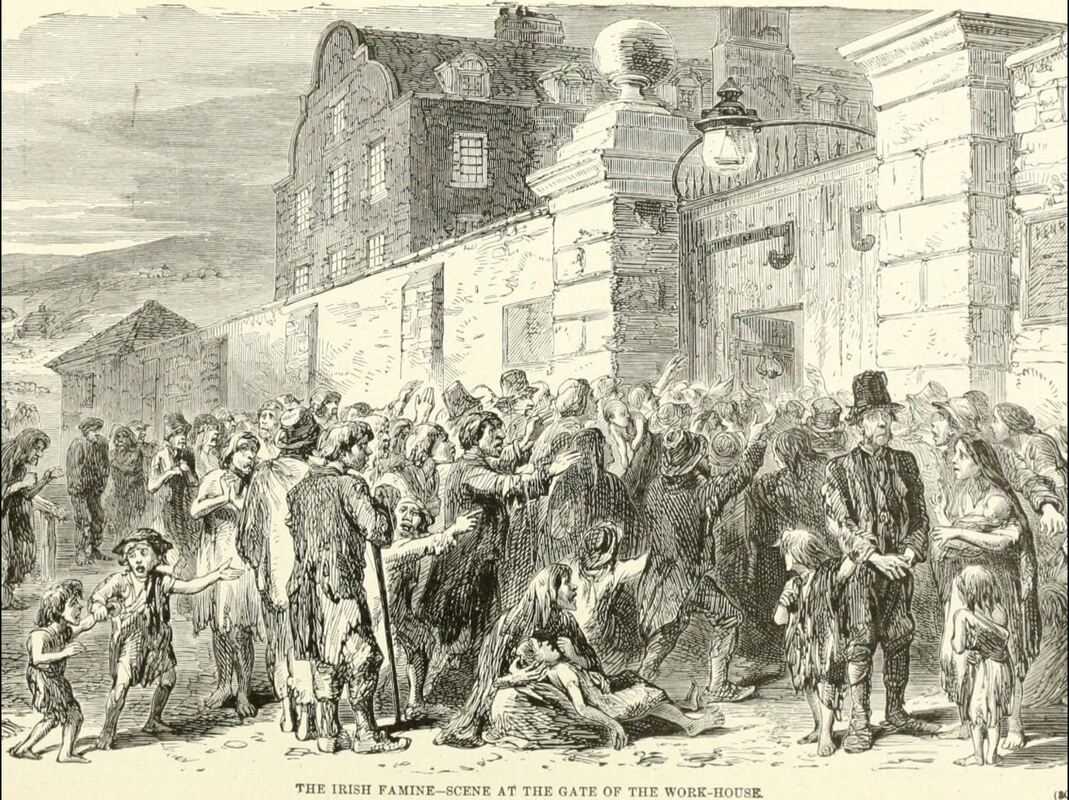

Around 1 million people died and another 1 million emigrated during the Irish Potato Famine.

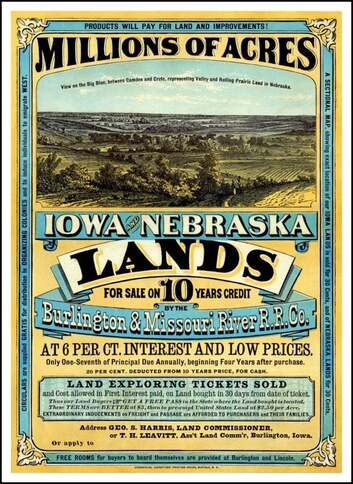

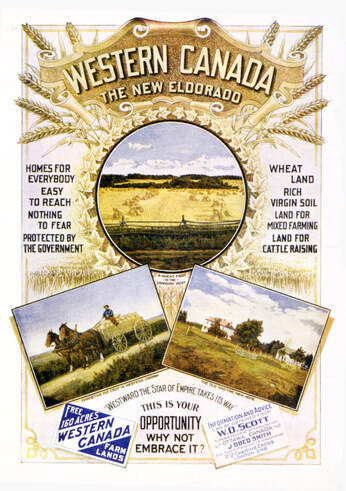

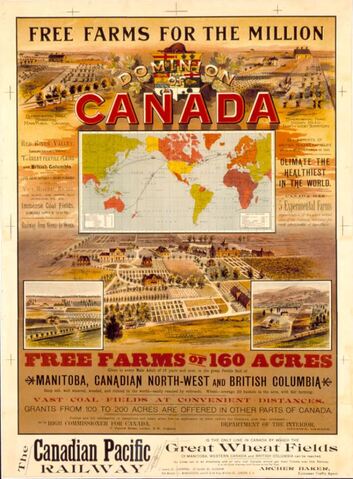

posters advertising free or cheap land in North America

|

Swedish emigrants board a ship bound for America. Roughly 20% of Sweden's male population and 15% of its female population moved away during the latter part of the 19th century.

|

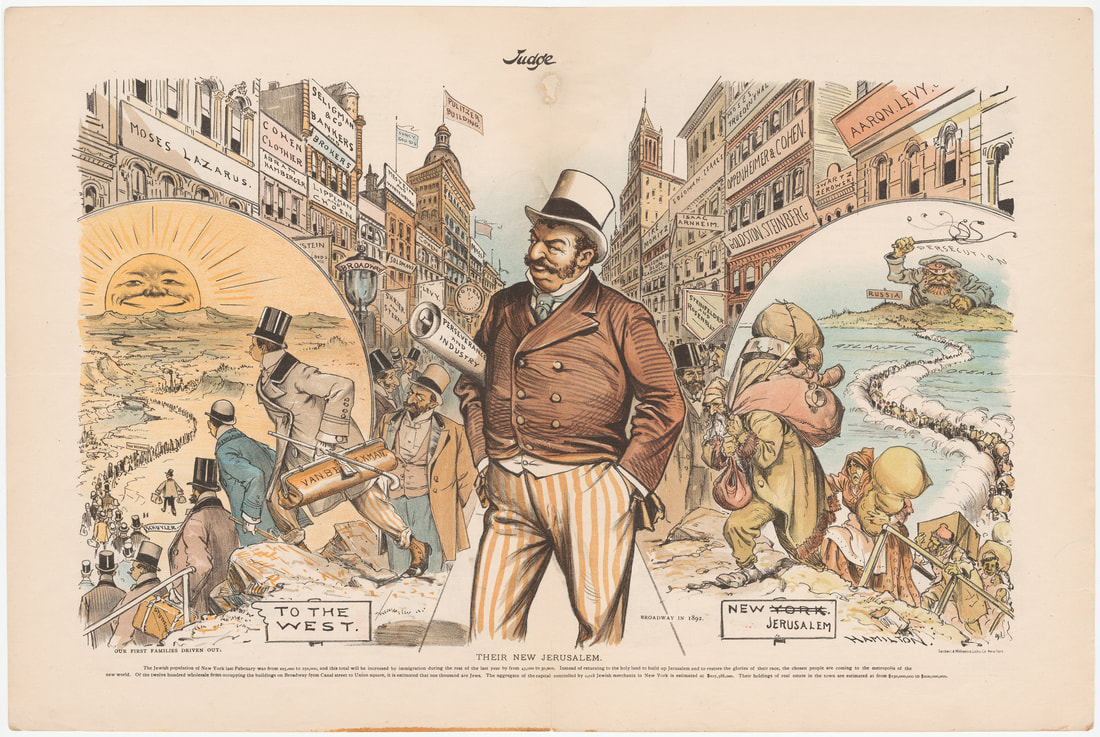

Czar Alexander II of Russia was assassinated in 1881. Seeking a scapegoat to blame, the Russian government and people launched pogroms against the empire's Jewish population. The result was a massive wave of emigration of Russian Jews, many of them to America, doubling the Jewish population of the United States in the 1880s alone. At the right, Russian Jewish immigrants flee the whip of persecution to New York as the waters of the Atlantic part to accommodate them (a reference to the Biblical Exodus led by Moses). In the center is a stereotypical Jewish businessman, well dressed and carrying a scroll labeled "Perseverance and Industry." Behind him is "Broadway in 1892," with Jewish names on every building from clothiers and fancy goods to bankers and brokers. At the left, well-dressed emigrants descended from New York's original Dutch settlers - Schuyler, Stuyvesant, Van Rensselaer, Van Beekman - head west over the caption "Our First Families Driven Out."

|

Urban Growth, Starvation, and Emigration Quizlet (comprehensive)

Urban Growth, Starvation, and Emigration Quizlet (abridged)

|

Victorian Society

Objective: Explain the causes and consequences of social developments resulting from industrialization.

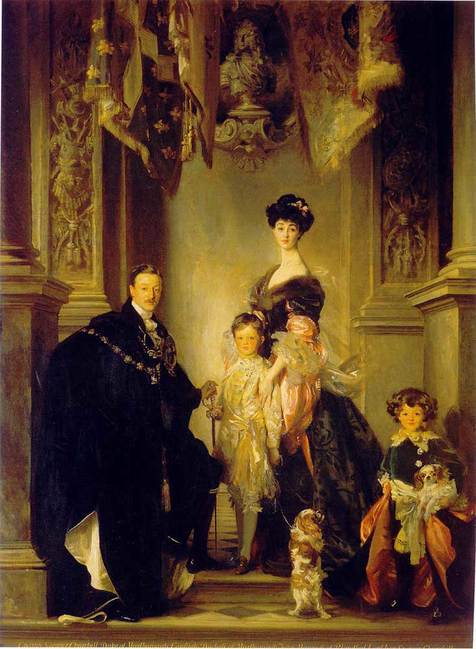

- In some of the less industrialized areas of Europe, the dominance of agricultural elites continued into the 20th century.

- In industrialized areas of Europe (i.e., western and northern Europe), socioeconomic changes created divisions of labor that led to the development of self-conscious classes, including the proletariat and the bourgeoisie.

- Bourgeois families became focused on the nuclear family and the cult of domesticity, with distinct gender roles for men and women.

- Class identity developed and was reinforced through participation in philanthropic, political, and social associations among the middle classes, and in mutual aid societies and trade unions among the working classes.

- Economic motivations for marriage, while still important for all classes, diminished as the middle-class notion of companionate marriage began to be adopted by the working classes.

|

Portrait of the 9th Duke of Marlborough with his family, John Singer Sargent (1905)

|

ARISTOCRACY

The fictional Crawley family from Downton Abbey faces many of the challenges to tradition that the landed aristocracy confronted by the early 20th century.

|

|

Mary Poppins' Banks family is a typical Victorian/Edwardian era middle class family.

|

|

'Street Urchins', Paul Martin (1893) - Life sucked for the Victorian poor.

|

WORKING CLASS

|

|

Princess Catherine Hilda Duleep Singh was the daughter of an Indian prince and an Ethiopian-German aristocrat. As her father was a frequent guest of Queen Victoria, Catherine became a member of British high society. She was an active suffragette who joined Emmeline Pankhurst's crusade for votes for women. In the 1930s, she lived in Nazi Germany with her partner, Lina Schäfer, where she helped Jewish refugees escape to England.

|

|

Victorian Society Quizlet (comprehensive)

Victorian Society Quizlet (abridged)

|

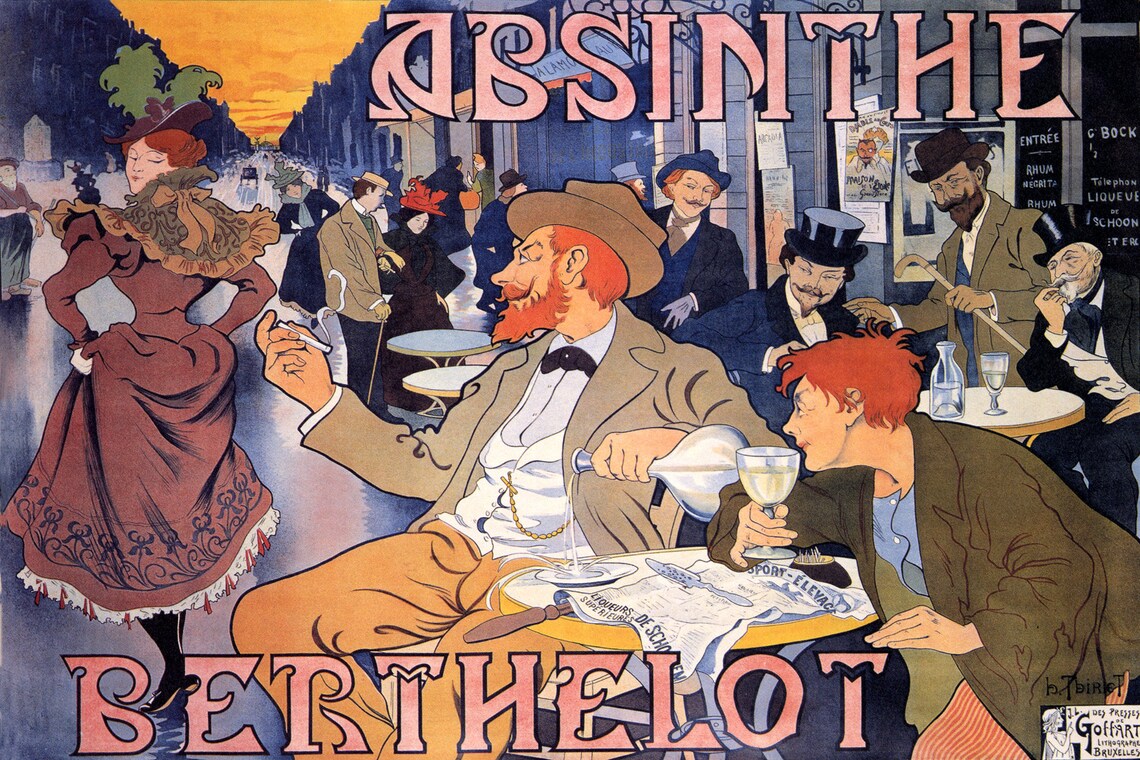

La Belle Époque

Objective: Explain how innovations and advances in technology during the Industrial Revolutions led to economic and social change.

Paris during La Belle Époque

Rising Standard of Living

- A heightened consumerism developed as a result of the second industrial revolution.

- Industrialization and mass marketing increased both the production and demand for a new range of consumer goods— including clothing, processed foods, and labor-saving devices—and created more leisure opportunities.

- By the end of the century, higher wages, laws restricting the labor of children and women, social welfare programs, improved diet, and increased access to birth control affected the quality of life for the working class.

- Leisure time centered increasingly on the family or small groups, concurrent with the development of activities and spaces to use that time.

French postcards from 1899 imagining life in the year 2000.

|

Advertisements for Pears' Soap embody 19th century middle-class Victorian values of purity and provide jingoistic support for the British Empire.

|

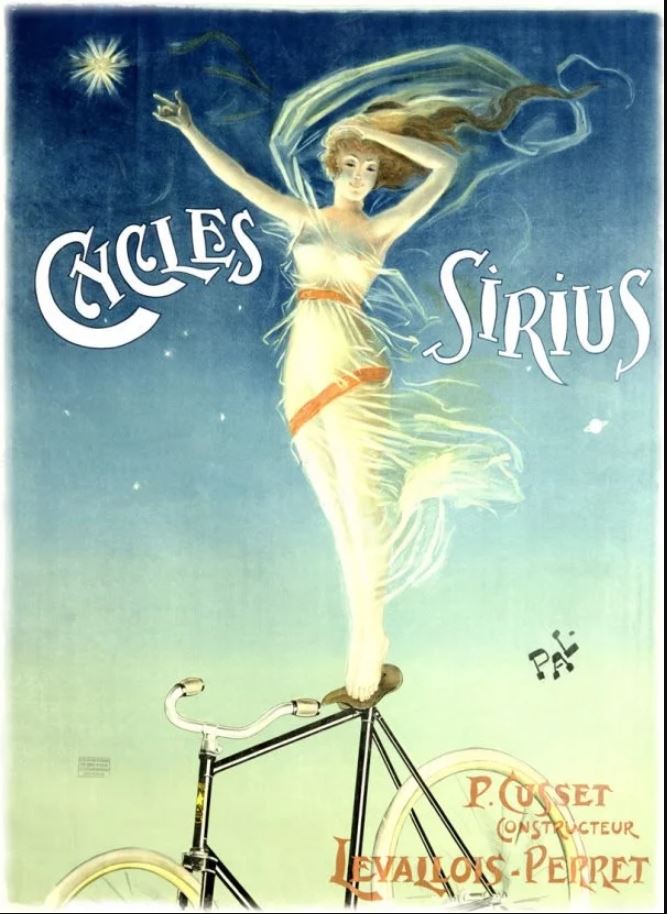

Art Nouveau advertisements from the 1890s

Recreation

|

Victorian Era sports

|

Thomas Cook & Co. guided tourists.

|

|

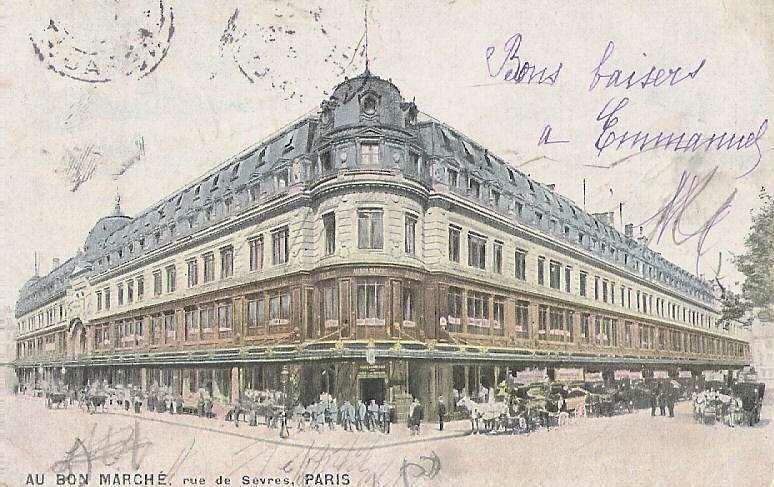

Le Bon Marché was one of the first department stores.

advertisement for Harrod’s, 1923

|

Harrod’s was the preeminent department store for high-end shopping in London.

|

The iron and glass covered Galleria Vittorio Emanuele II in Milan opened in 1877. It is is Italy's oldest active shopping gallery.

Blackpool was a Victorian-era beach side resort which offered the middle and working classes all the entertaining marvels of the Modern Age.

|

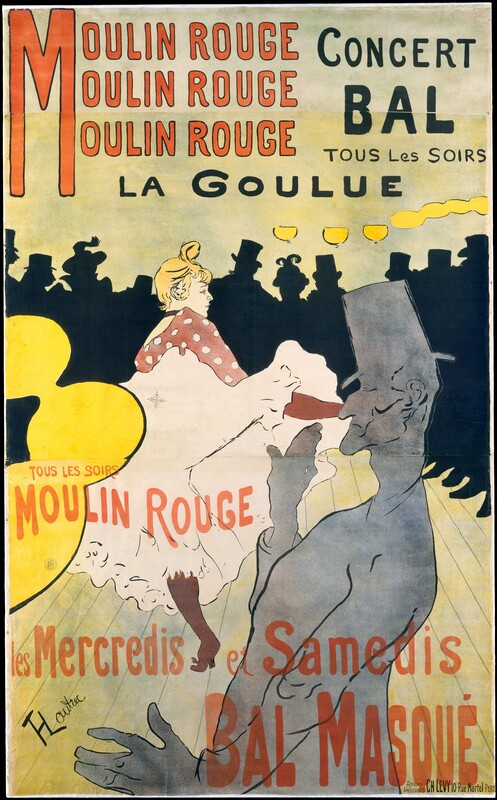

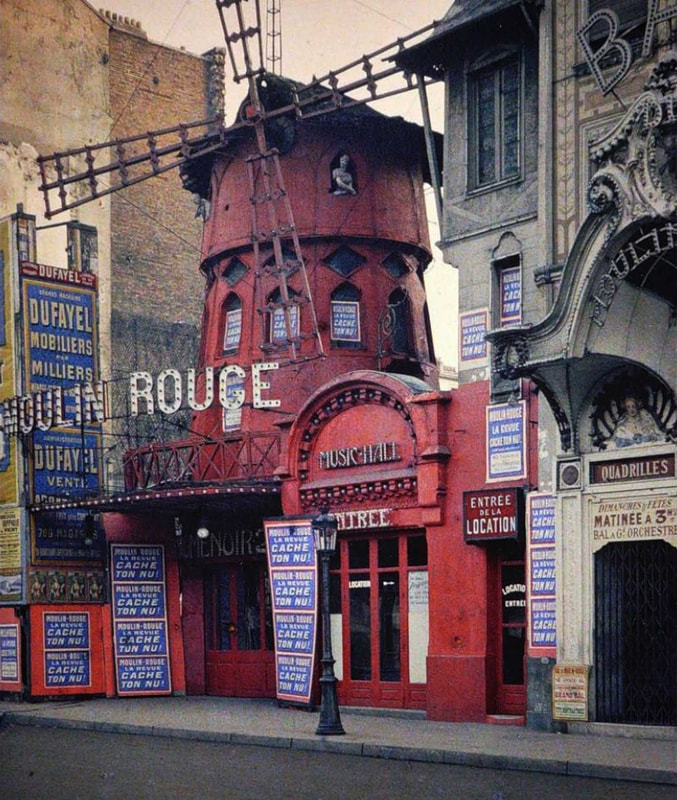

The Moulin Rouge cabaret, birthplace of the can-can, allowed Paris' bourgeoisie and proletariat to mix.

|

|

La Belle Époque Quizlet (comprehensive)

La Belle Époque Quizlet (abridged)

|