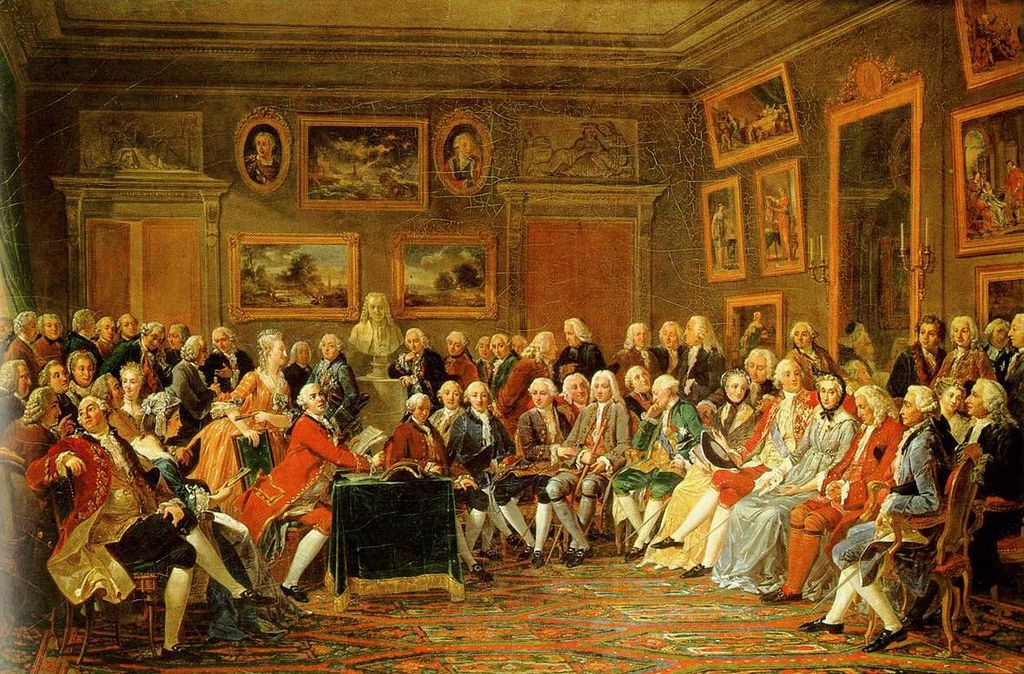

A gathering in the salon of Madame Geoffrin, 1755

Belief in progress, along with improved social and economic conditions, spurred significant gains in literacy and education as well as the creation of a new culture of the printed word — including novels, newspapers, periodicals, and such reference works as Diderot’s Encyclopédie — for a growing educated audience.

Reason,

c. 1648-1815 CE

Contents

During the 16th and 17th centuries, Europeans developed new approaches to and methods for looking at the natural world in what historians have called the Scientific Revolution. Aristotle’s classical cosmology and Ptolemy’s astronomical system came under increasing scrutiny from natural philosophers (later called scientists) such as Copernicus, Galileo, and Newton. The philosophers Francis Bacon and René Descartes articulated comprehensive theories of inductive and deductive reasoning to give the emerging scientific method a sound foundation. Bacon urged the collection and analysis of data about the world and spurred the development of an international community of natural philosophers dedicated to the vast enterprise of what came to be called natural science. In medicine, the new approach to knowledge led physicians such as William Harvey to undertake observations that produced new explanations of anatomy and physiology and to challenge the traditional theory of health and disease (the four humors) espoused by Galen in the second century.

The articulation of natural laws, often expressed mathematically, became the goal of science, especially after the Europeans’ encounters with the Western Hemisphere. The explorations produced new knowledge of geography and the world’s peoples through direct observation, and this seemed to give credence to new approaches to knowledge more generally. Yet while they developed inquiry-based epistemologies, Europeans also continued to draw upon longstanding explanations of the natural world.

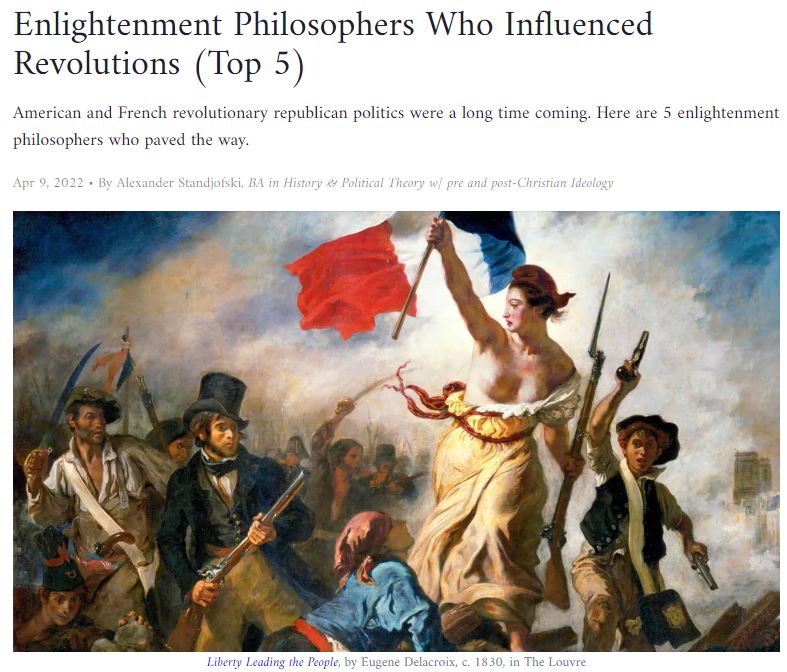

During the 17th and 18th centuries, Europeans applied the methods of the new science—such as empiricism, mathematics, and skepticism—to human affairs. During the Enlightenment, intellectuals such as Rousseau, Voltaire, and Diderot aimed to replace faith in divine revelation with faith in human reason and classical values. In economics and politics, liberal theorists such as John Locke and Adam Smith questioned absolutism and mercantilism by arguing for the authority of natural law and the market. Belief in progress, along with improved social and economic conditions, spurred significant gains in literacy and education as well as the creation of a new culture of the printed word—including novels, newspapers, periodicals, and such reference works as Diderot’s Encyclopédie—for a growing educated audience.

Alongside several movements of religious revival that occurred during the 18th century, European elite culture embraced skepticism, secularism, and atheism for the first time in European history. From the beginning of this period, Protestants and Catholics grudgingly tolerated each other following the religious warfare of the previous two centuries. By 1800, most governments had extended toleration to Christian minorities and in some states even to Jews. Religion was viewed increasingly as a matter of private rather than public concern.

The new rationalism did not sweep all before it; in fact, it coexisted with a revival of sentimentalism and emotionalism. Until about 1750, Baroque art and music glorified religious feeling and drama as well as the grandiose pretensions of absolute monarchs. During the French Revolution, romanticism and nationalism implicitly challenged what some saw as the Enlightenment’s overemphasis on reason. These Counter-Enlightenment views laid the foundations for new cultural and political values in the 19th century. Overall, intellectual and cultural developments reflected a new worldview in which rationalism, skepticism, scientific investigation, and a belief in progress generally dominated. At the same time, other worldviews stemming from religion, nationalism, and romanticism remained influential.

Source: https://apcentral.collegeboard.org/pdf/ap-european-history-course-and-exam-description.pdf

The articulation of natural laws, often expressed mathematically, became the goal of science, especially after the Europeans’ encounters with the Western Hemisphere. The explorations produced new knowledge of geography and the world’s peoples through direct observation, and this seemed to give credence to new approaches to knowledge more generally. Yet while they developed inquiry-based epistemologies, Europeans also continued to draw upon longstanding explanations of the natural world.

During the 17th and 18th centuries, Europeans applied the methods of the new science—such as empiricism, mathematics, and skepticism—to human affairs. During the Enlightenment, intellectuals such as Rousseau, Voltaire, and Diderot aimed to replace faith in divine revelation with faith in human reason and classical values. In economics and politics, liberal theorists such as John Locke and Adam Smith questioned absolutism and mercantilism by arguing for the authority of natural law and the market. Belief in progress, along with improved social and economic conditions, spurred significant gains in literacy and education as well as the creation of a new culture of the printed word—including novels, newspapers, periodicals, and such reference works as Diderot’s Encyclopédie—for a growing educated audience.

Alongside several movements of religious revival that occurred during the 18th century, European elite culture embraced skepticism, secularism, and atheism for the first time in European history. From the beginning of this period, Protestants and Catholics grudgingly tolerated each other following the religious warfare of the previous two centuries. By 1800, most governments had extended toleration to Christian minorities and in some states even to Jews. Religion was viewed increasingly as a matter of private rather than public concern.

The new rationalism did not sweep all before it; in fact, it coexisted with a revival of sentimentalism and emotionalism. Until about 1750, Baroque art and music glorified religious feeling and drama as well as the grandiose pretensions of absolute monarchs. During the French Revolution, romanticism and nationalism implicitly challenged what some saw as the Enlightenment’s overemphasis on reason. These Counter-Enlightenment views laid the foundations for new cultural and political values in the 19th century. Overall, intellectual and cultural developments reflected a new worldview in which rationalism, skepticism, scientific investigation, and a belief in progress generally dominated. At the same time, other worldviews stemming from religion, nationalism, and romanticism remained influential.

Source: https://apcentral.collegeboard.org/pdf/ap-european-history-course-and-exam-description.pdf

The Scientific Revolution

Objective: Explain how understanding of the natural world developed and changed during the Scientific Revolution.

Scientific Revolution: Crash Course European History #12

There was a lot of bad stuff going on in Europe in the 17th century. We've seen wars, plagues, and unrest of all types. But there is some good news. Huge advances were underway in the scientific community in Europe at this time. In this video we'll look at the progress of knowledge with Galileo, Copernicus, Kepler, Harvey, Newton, and more.

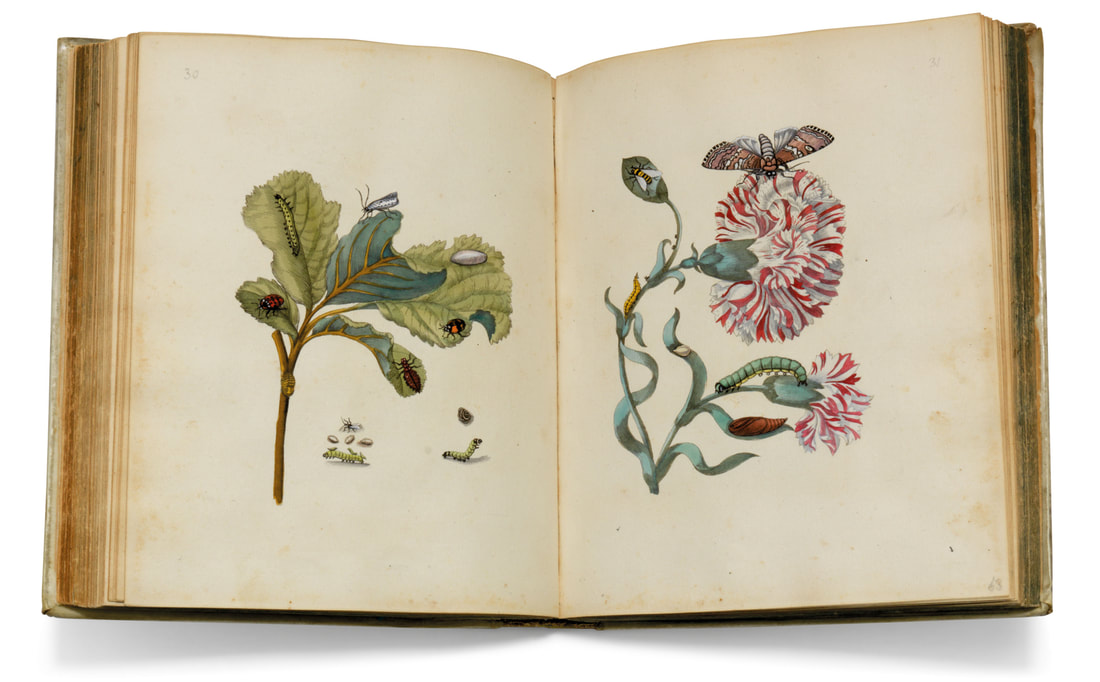

Maria Sibylla Merian, a pioneer of entomology, published her detailed observations of European and South American insects in Metamorphosis (1705).

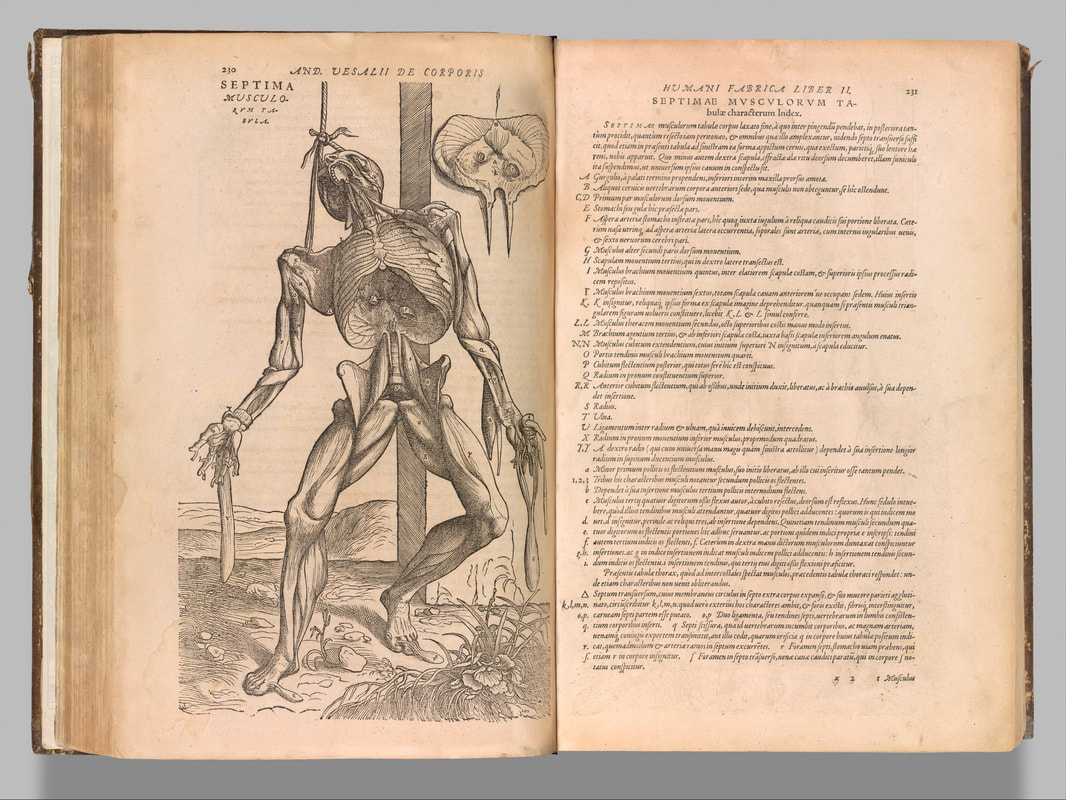

Andreas Vesalius presents a careful examination of the organs and the complete structure of the human body in On the Fabric of the Human Body (1543).

|

Data collected from Tycho Brahe's careful astronomical observations allowed Johannes Kepler to develop the laws of planetary motion.

Émilie du Châtelet elaborated on Isaac Newton's theories in Foundations of Physics (1740). Although she had one of the most talented minds of her generation, her ideas were largely ignored during her lifetime due to her gender. She was also the great love of Voltaire's life, and his intellectual partner.

|

|

Colbert Presenting the Members of the Royal Academy of Sciences to Louis XIV in 1667 by Henri Testelin

|

The Scientific Revolution (comprehensive)

The Scientific Revolution (abridged)

|

The Enlightenment

The Enlightenment: Crash Course European History #18

This week, we're talking about the Enlightenment. In this video, you'll learn about the ideas of Voltaire, Rousseau, Montesquieu, Kant, Smith, Hume, and a bunch of other people whose ideas have been so impactful, they still influence the way we think about the world today.

The Social Contract

Objective: Compare the different forms of political power that developed in Europe from 1648 to 1815.

|

Philosophes

Objective: Explain the causes and consequences of Enlightenment thought on European intellectual development and society from 1648 to 1815.

- Intellectuals, including Voltaire and Diderot, began to apply the principles of the Scientific Revolution to society and human institutions.

- Enlightenment thought, which focused on concepts such as empiricism, skepticism, human reason, rationalism, and classical sources of knowledge, challenged the prevailing patterns of thought with respect to social order, institutions of government, and the role of faith.

- Despite censorship, increasingly numerous and varied printed materials served a growing literate public and led to the development of public opinion.

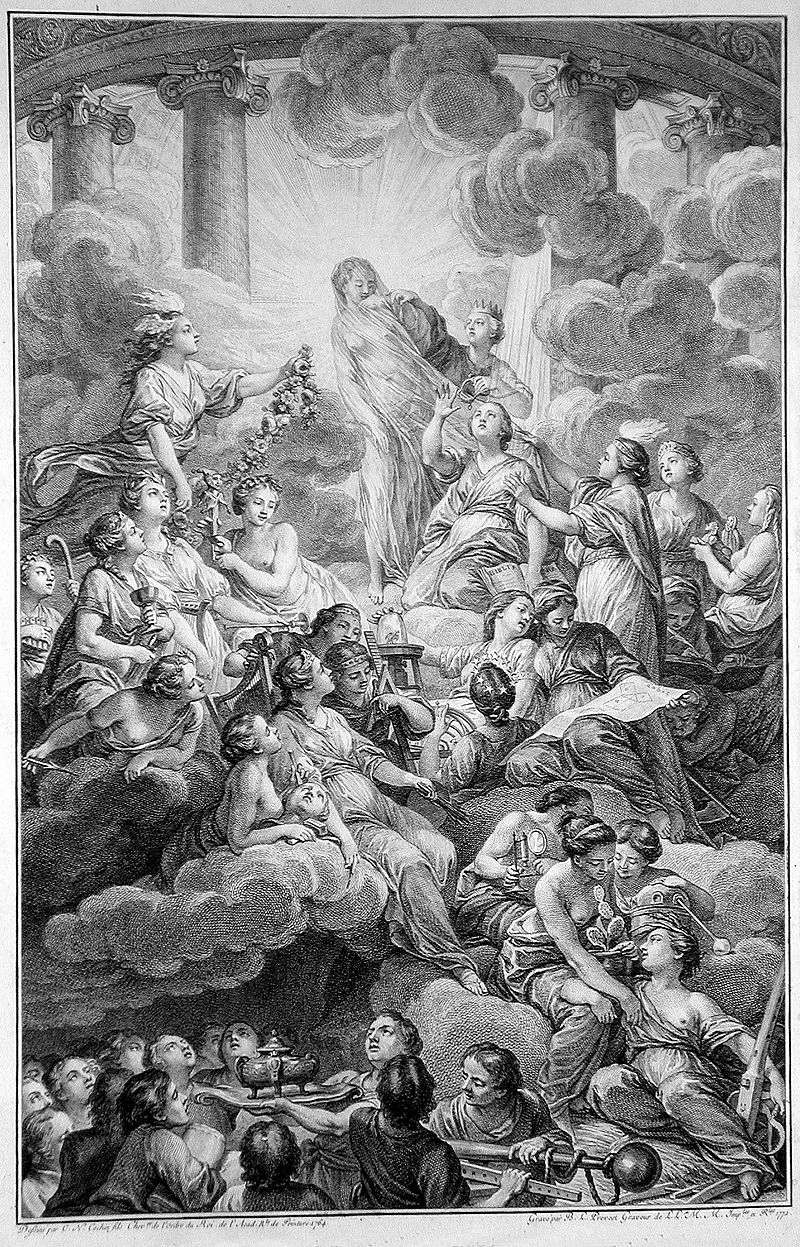

"If there is something you know, communicate it. If there is something you don't know, search for it." — An engraving from the 1772 edition of the Encyclopédie; Truth, in the top center, is surrounded by light and unveiled by the figures to the right, Philosophy and Reason

Salons

Afternoon Tea at the Temple by Michel-Barthélémy Ollivier (1764)

|

Freemasons, whose members included Voltaire, John Locke, Haydn, Mozart, George Washington, and Benjamin Franklin, espoused Enlightenment ideals. This secret society was often misunderstood and persecuted, especially by the Catholic Church.

|

|

|

The Enlightenment (comprehensive)

The Enlightenment (abridged)

|

Nature

Objective: Explain the causes and consequences of Enlightenment thought on European intellectual development and society from 1648 to 1815.

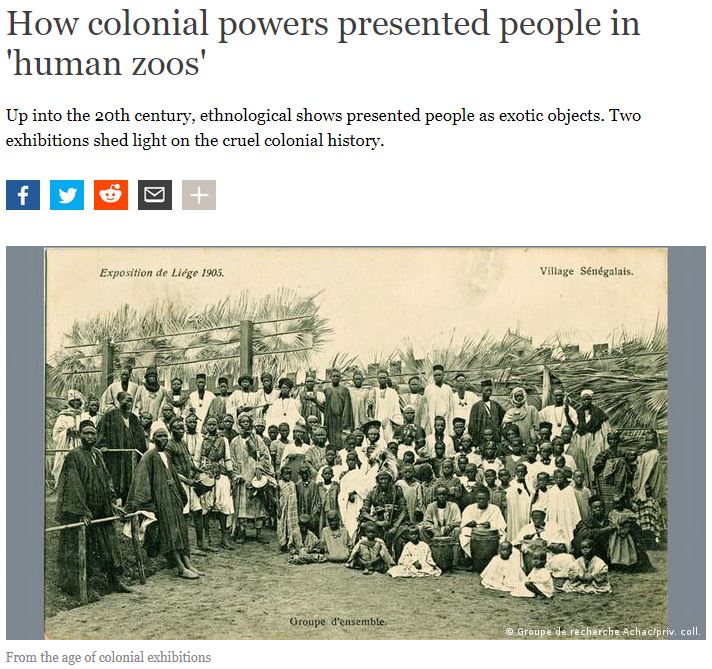

Noble Savages

Resolution and Adventure with fishing craft in Matavai Bay by William Hodges (1776) depicts British explorer James Cook's second expedition in Tahiti.

|

|

|

Natural Religion

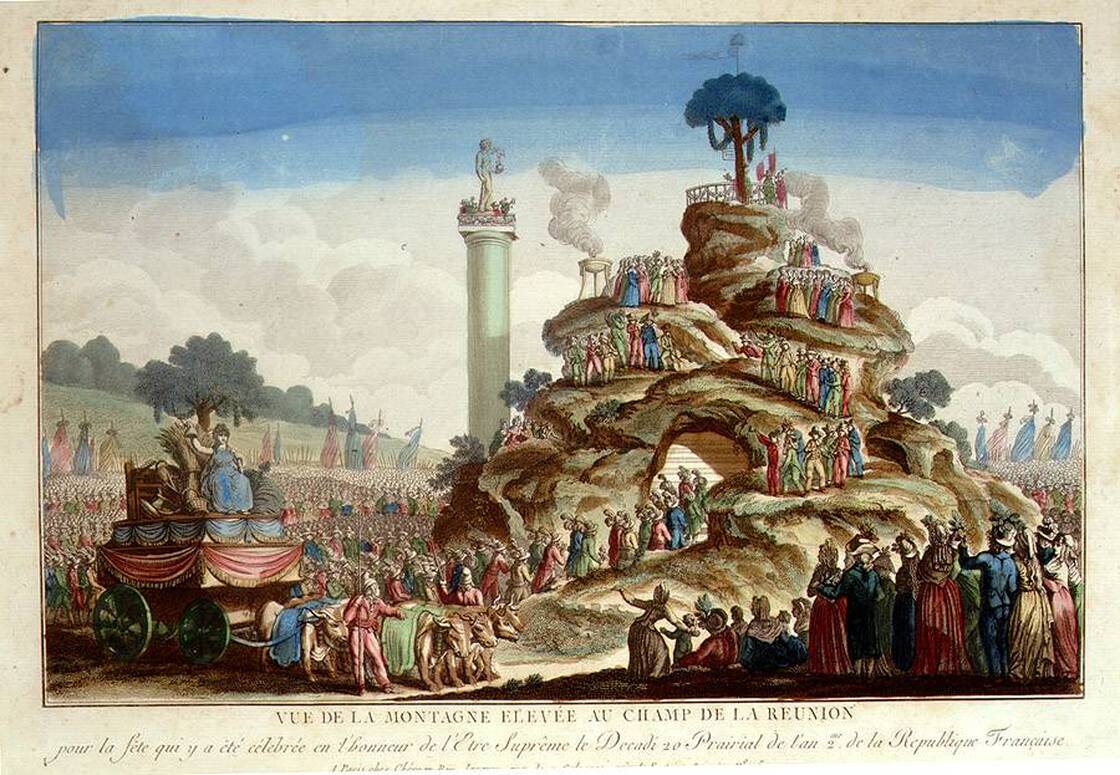

French Revolutionary leaders tried to replace Catholicism first with the atheistic Cult of Reason and then the deistic Cult of the Supreme Being. A Festival of the Supreme Being was led by Robespierre at the zenith of power. Jacques-Louis David designed a plaster-and cardboard mountain topped with a liberty tree from which Robespierre descended. Jacques-Alexis Thuriot was heard saying "Look at the bugger; it’s not enough for him to be master, he has to be God".

- Intellectuals, including Voltaire and Diderot, developed new philosophies of deism, skepticism, and atheism.

- Religion was viewed increasingly as a matter of private rather than public concern.

|

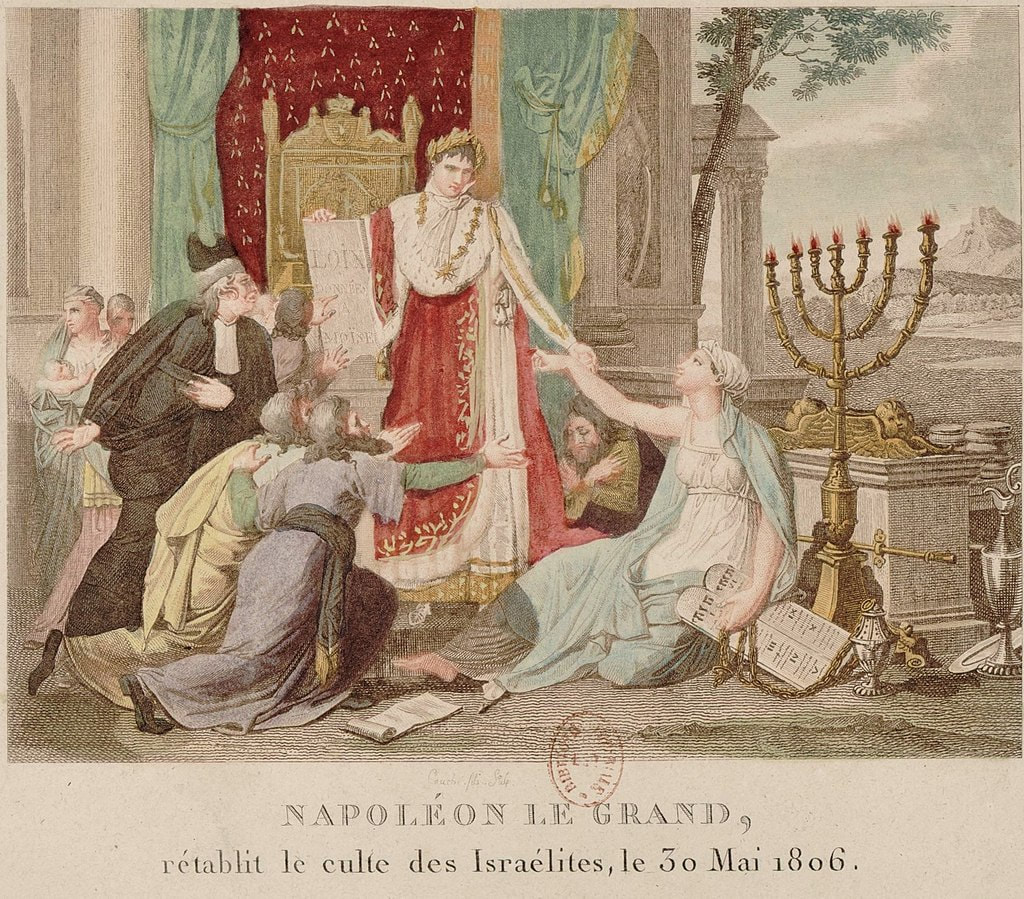

Napoleon grants the Jews freedom to worship in this print (1806).

|

|

Noble Savages and Natural Religion (comprehensive)

Noble Savages and Natural Religion (abridged)

|

18th Century Art and Literature

Objective: Explain how European cultural and intellectual life was maintained and changed throughout the period from 1648 to 1815.

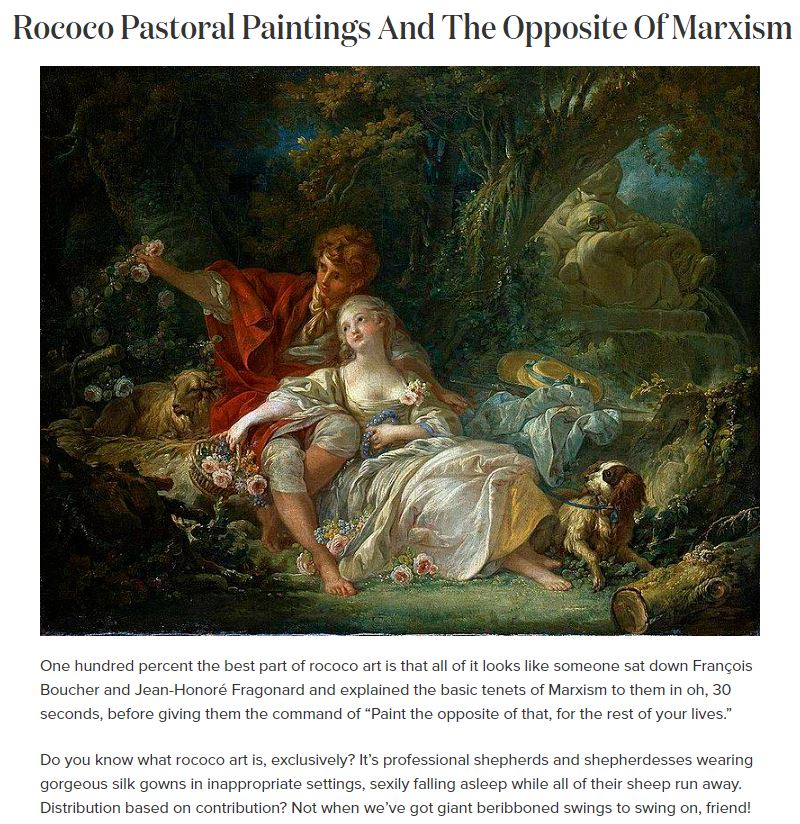

Rococo

- The arts moved from the celebration of religious themes and royal power to an emphasis on private life and the public good.

- 18th-century art and literature increasingly reflected the outlook and values of commercial and bourgeois society.

Neoclassical Art and Classical Music

18th Century British Literature

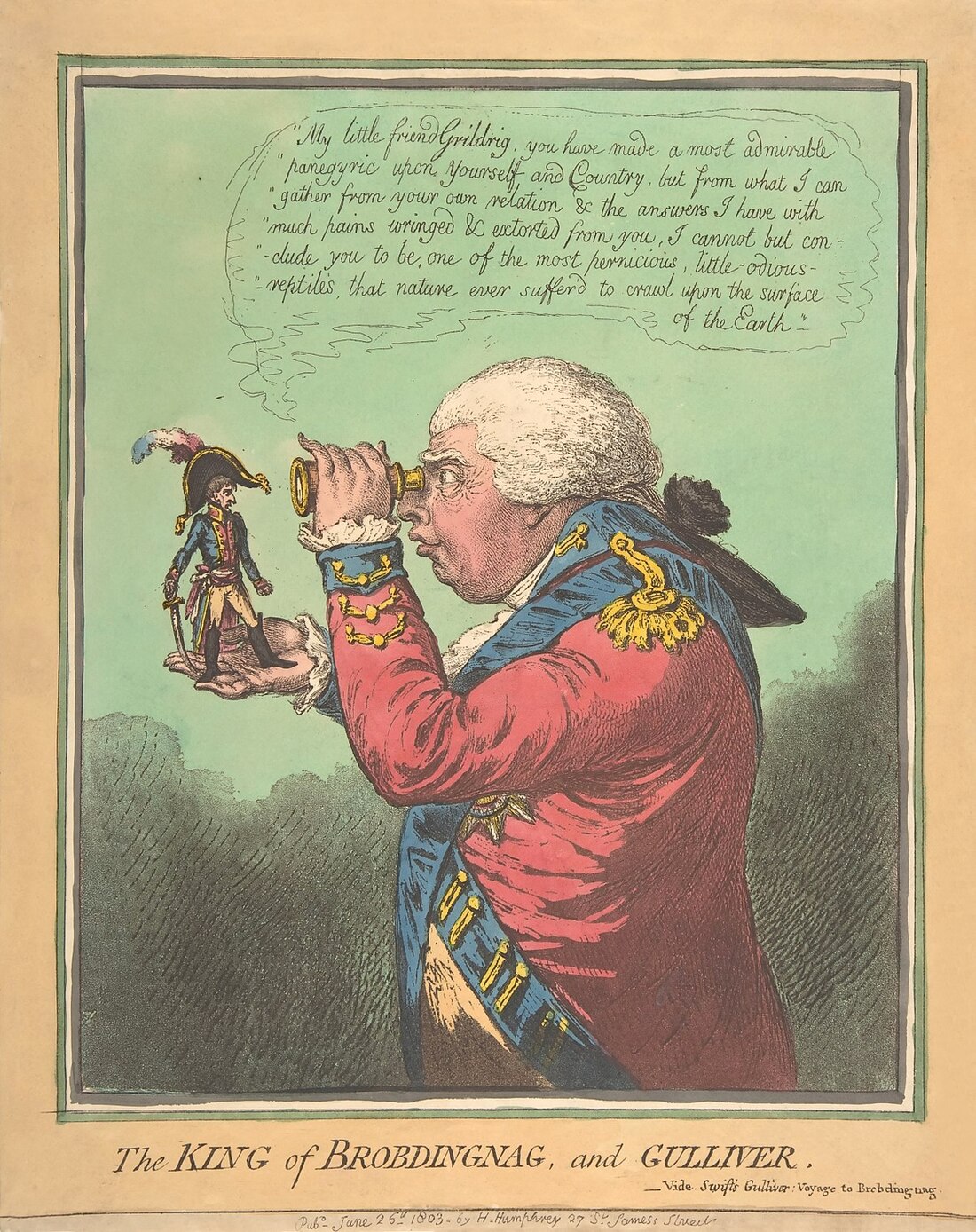

James Gilray depicts George III as the "King of Brobdingnag" and Napoleon as the title character of Jonathan Swift's Gulliver's Travels.

|

|

|

|

18th Century Art and Literature (comprehensive)

18th Century Art and Literature (abridged)

|