Rulers soon recognized that capitalist enterprise offered them a revenue source to support state functions, and the competition among states was extended into the economic arena.

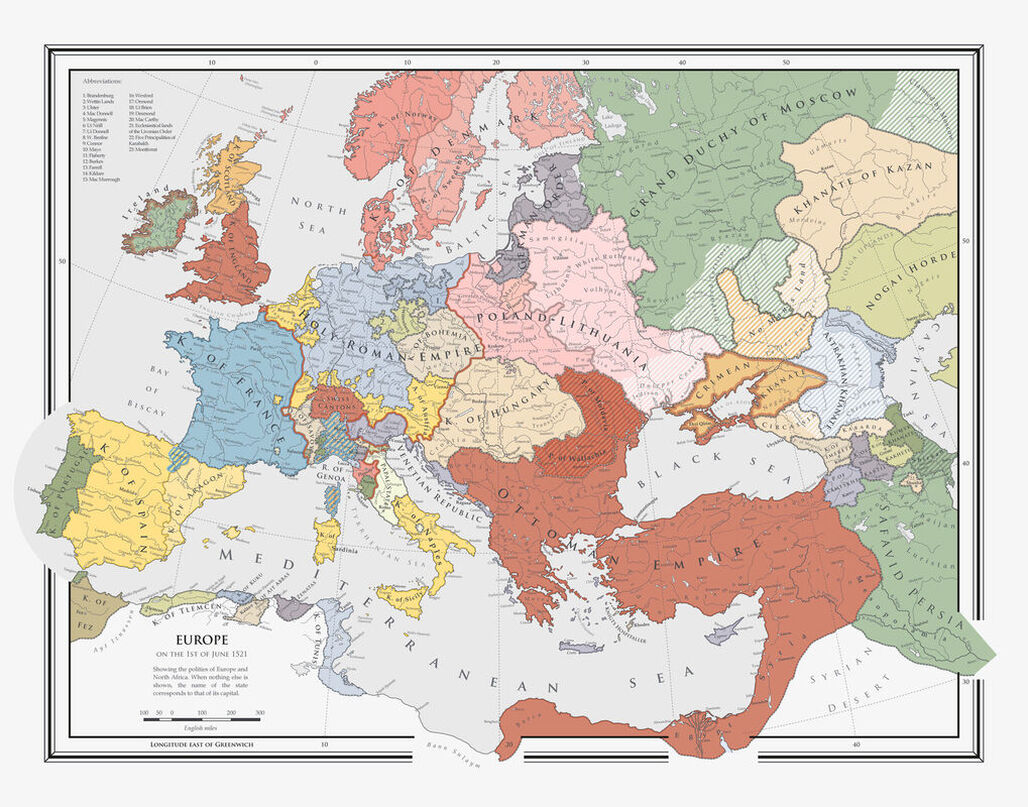

Renaissance,

c. 1450-1648 CE

Contents

A. Early Modern Society

B. The Renaissance

C. The New Monarchies

- Political Theory

- The Military Revolution

- Trastámara Spain

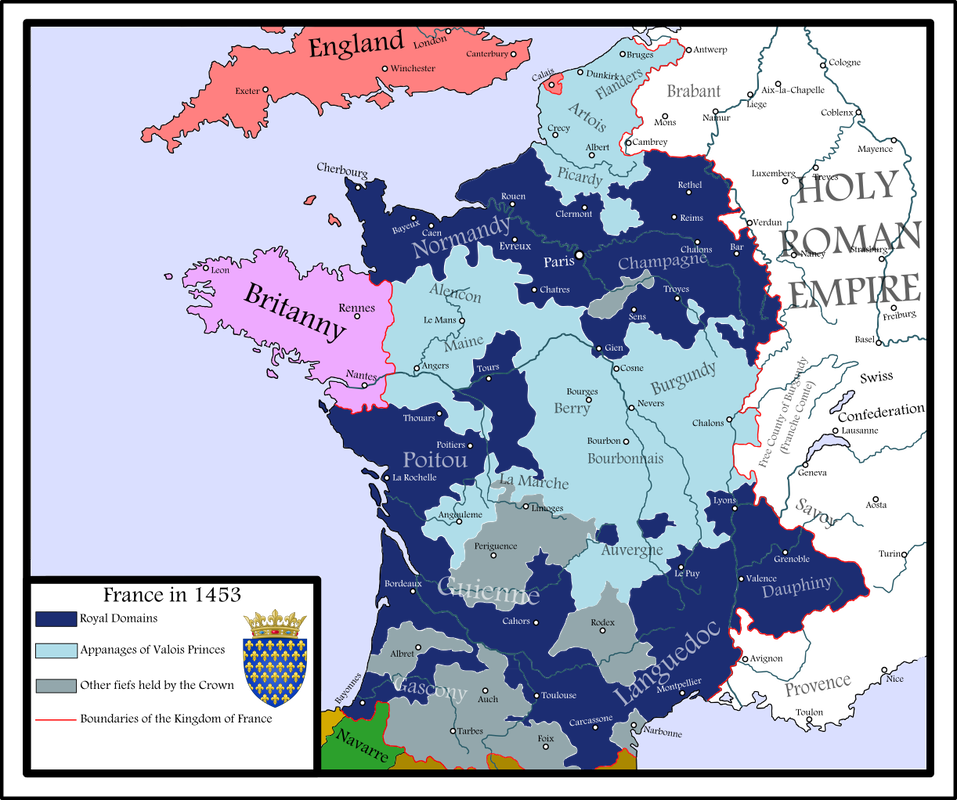

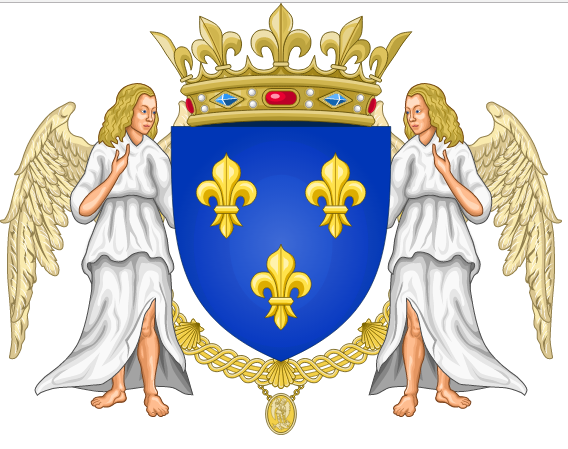

- Valois France

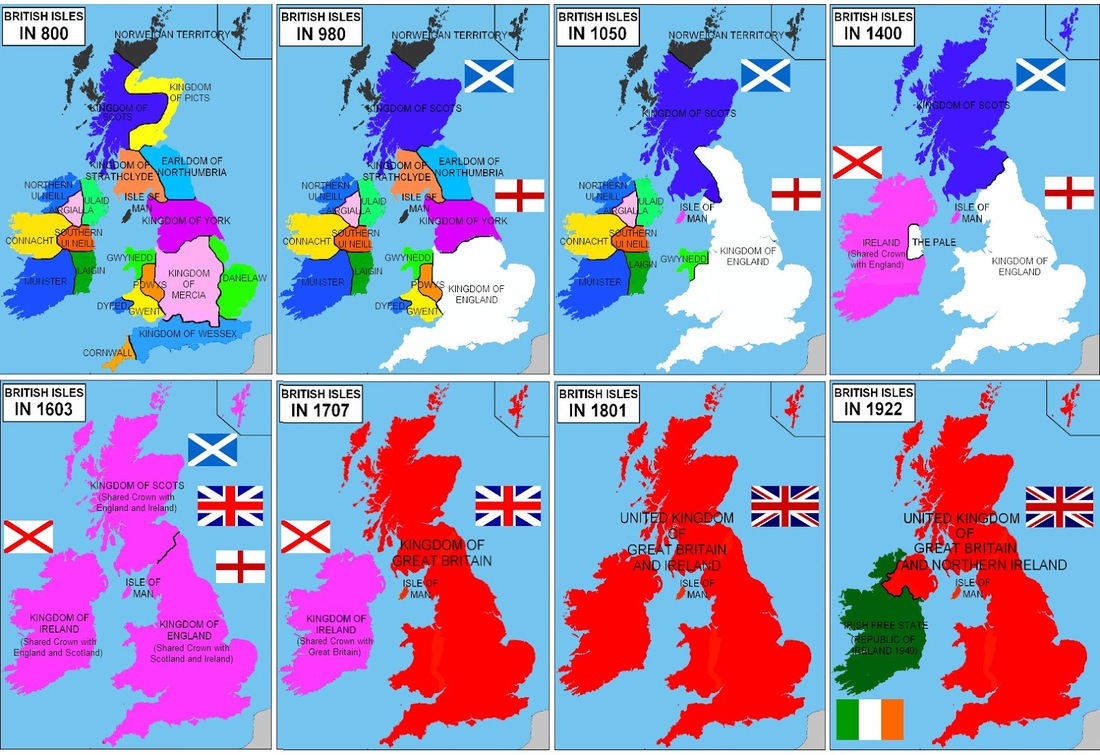

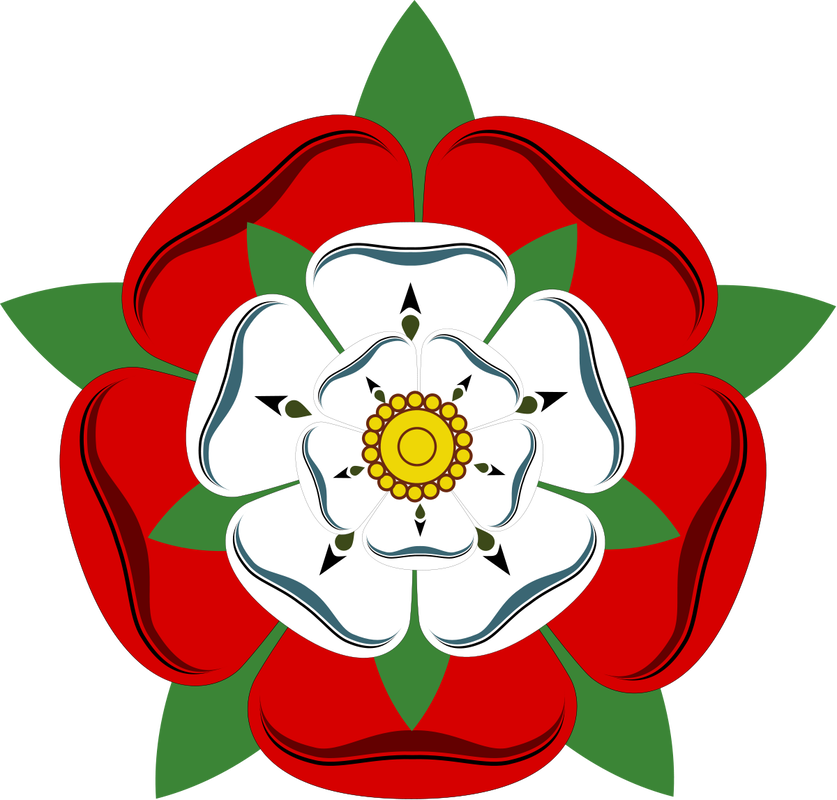

- Tudor England

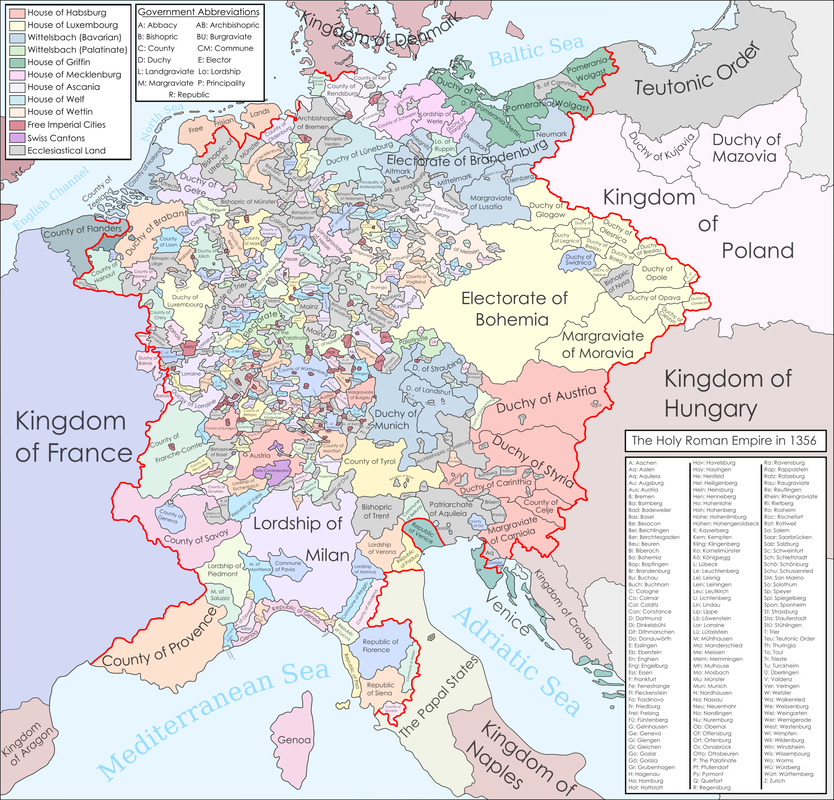

- The Holy Roman Empire

- War and Diplomacy

D. Spain and England

E. Sweden, Poland, and Russia

F. The Ottoman Empire

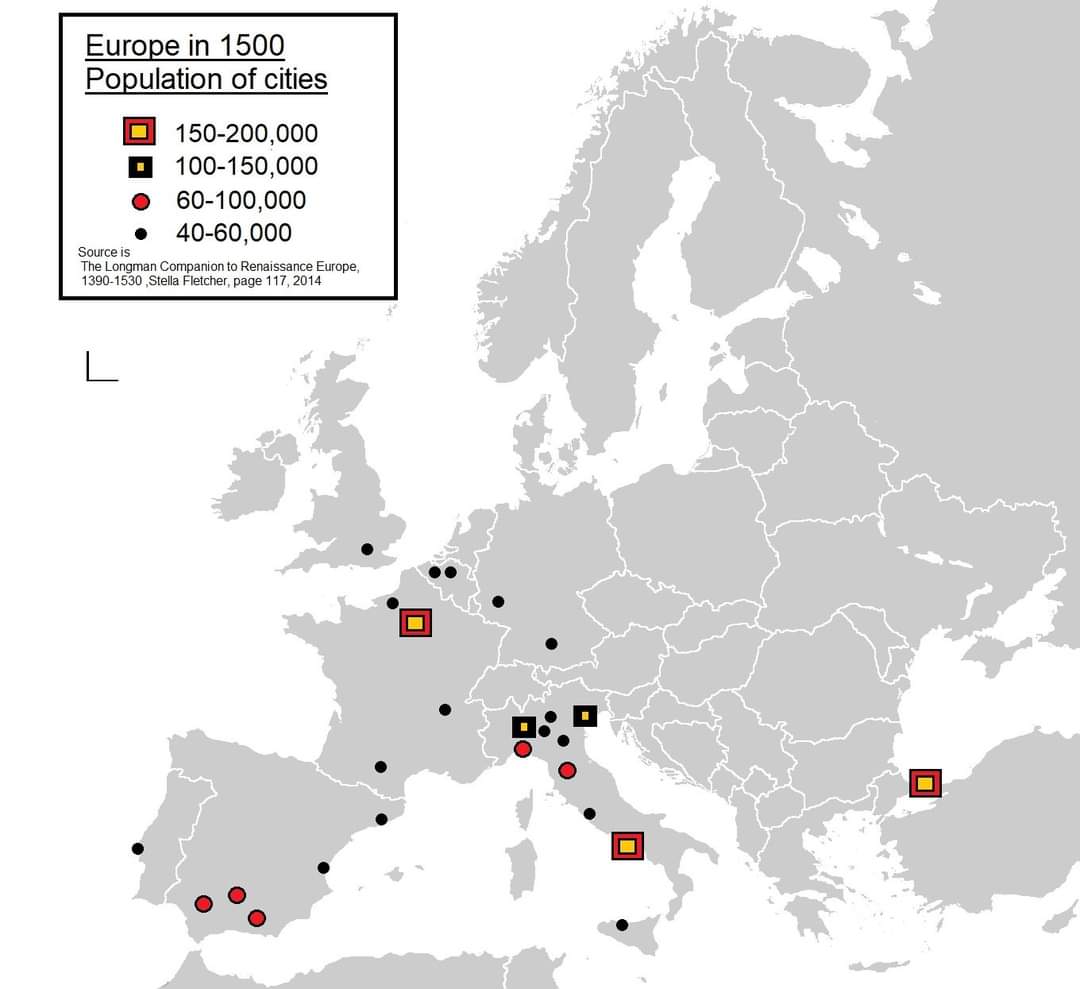

In the 16th and 17th centuries, Europeans experienced profound economic and social changes. The influx of precious metals from the Americas and the gradual recovery of Europe’s population from the Black Death caused a significant rise in the cost of goods and services by the 16th century, known as the price revolution. The new pattern of economic enterprise and investment that arose from these changes would come to be called capitalism. Family-based banking houses were supplanted by broadly integrated capital markets in Genoa, then in Amsterdam, and later in London. These and other urban centers became increasingly active consumer markets for a variety of luxury goods and commodities.

Rulers soon recognized that capitalist enterprise offered them a revenue source to support state functions, and the competition among states was extended into the economic arena. The drive for economic profit and the increasing scale of commerce stimulated the creation of joint-stock companies to conduct overseas trade and colonization. These demographic and economic changes altered many Europeans’ daily lives. As population increased in the 16th century, the price of grain rose and diets deteriorated, all as monarchs were increasing taxes to support their larger state militaries. All but the wealthy were vulnerable to food shortages, and even the wealthy had no immunity to recurrent lethal epidemics.

Although hierarchy and privilege continued to define the social structure, the nobility and gentry expanded with the infusion of new blood from the commercial and professional classes. By the mid-17th century, war, economic contraction, and slackening population growth contributed to the disintegration of older communal values. Growing numbers of the poor became beggars or vagabonds, straining the traditional systems of charity and social control.

In eastern Europe, commercial development lagged and traditional social patterns continued; the nobility actually increased its power over the peasantry. Traditional town governments, dominated by craft guilds and traditional religious institutions, struggled to address growing poverty. The Reformation and Counter-Reformation stimulated a drive to regulate public morals, leisure activities, and the distribution of poor relief.

In both town and country, the family remained the dominant unit of production, and marriage remained an instrument of families’ social and economic strategies. The children of peasants and craft workers often labored alongside their parents. In the lower orders of society, men and women did not occupy separate spheres, although they performed different tasks. Economics often dictated later European marriage patterns. However, there were exceptions to this pattern: in the cities of Renaissance Italy, men in their early 30s often married teenaged women, and in eastern Europe, early marriage for both men and women continued to be the norm. Despite the growth of the market economy in which individuals increasingly made their own way, leisure activities tended to be communal, rather than individualistic and consumerist as they are today. Local communities enforced their customs and norms through crowd action and in some cases, rituals of public shaming.

Source: https://apcentral.collegeboard.org/pdf/ap-european-history-course-and-exam-description.pdf

Rulers soon recognized that capitalist enterprise offered them a revenue source to support state functions, and the competition among states was extended into the economic arena. The drive for economic profit and the increasing scale of commerce stimulated the creation of joint-stock companies to conduct overseas trade and colonization. These demographic and economic changes altered many Europeans’ daily lives. As population increased in the 16th century, the price of grain rose and diets deteriorated, all as monarchs were increasing taxes to support their larger state militaries. All but the wealthy were vulnerable to food shortages, and even the wealthy had no immunity to recurrent lethal epidemics.

Although hierarchy and privilege continued to define the social structure, the nobility and gentry expanded with the infusion of new blood from the commercial and professional classes. By the mid-17th century, war, economic contraction, and slackening population growth contributed to the disintegration of older communal values. Growing numbers of the poor became beggars or vagabonds, straining the traditional systems of charity and social control.

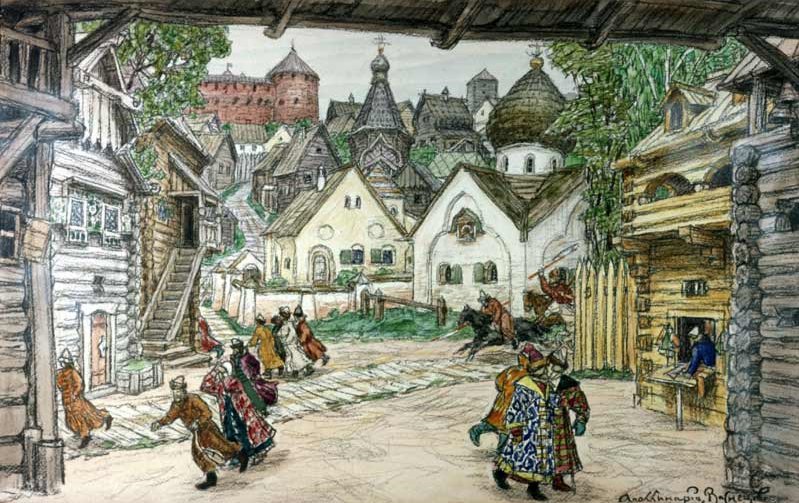

In eastern Europe, commercial development lagged and traditional social patterns continued; the nobility actually increased its power over the peasantry. Traditional town governments, dominated by craft guilds and traditional religious institutions, struggled to address growing poverty. The Reformation and Counter-Reformation stimulated a drive to regulate public morals, leisure activities, and the distribution of poor relief.

In both town and country, the family remained the dominant unit of production, and marriage remained an instrument of families’ social and economic strategies. The children of peasants and craft workers often labored alongside their parents. In the lower orders of society, men and women did not occupy separate spheres, although they performed different tasks. Economics often dictated later European marriage patterns. However, there were exceptions to this pattern: in the cities of Renaissance Italy, men in their early 30s often married teenaged women, and in eastern Europe, early marriage for both men and women continued to be the norm. Despite the growth of the market economy in which individuals increasingly made their own way, leisure activities tended to be communal, rather than individualistic and consumerist as they are today. Local communities enforced their customs and norms through crowd action and in some cases, rituals of public shaming.

Source: https://apcentral.collegeboard.org/pdf/ap-european-history-course-and-exam-description.pdf

New legal and political theories, embodied in the codification of law, strengthened state institutions, which increasingly took control of the social and economic order from traditional religious and local bodies. ... By the end of the Thirty Years’ War, a new state system had emerged based on sovereign nation-states and the balance of power.

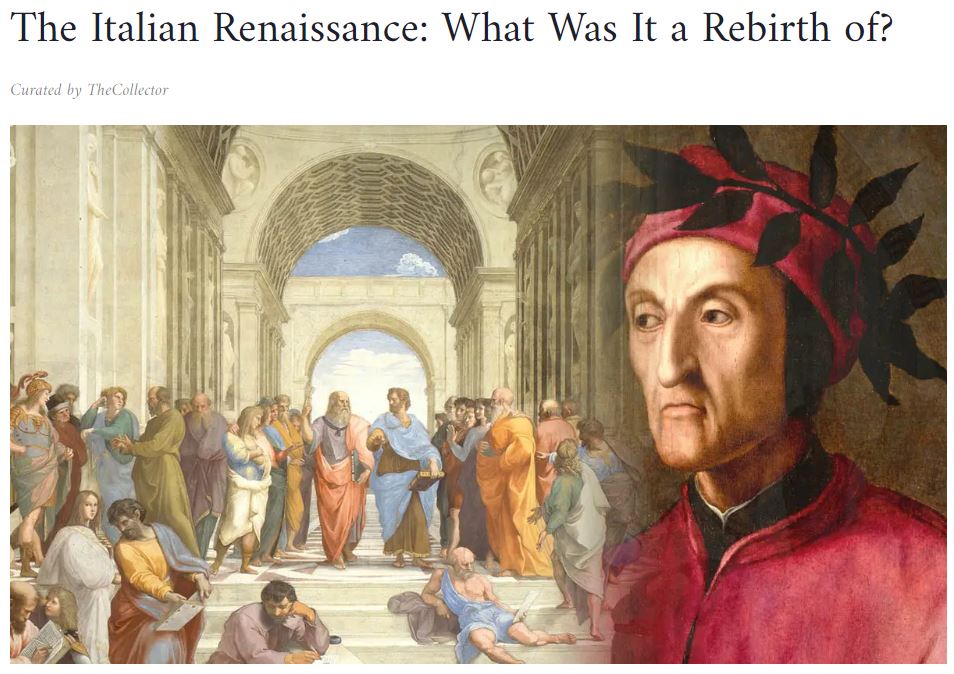

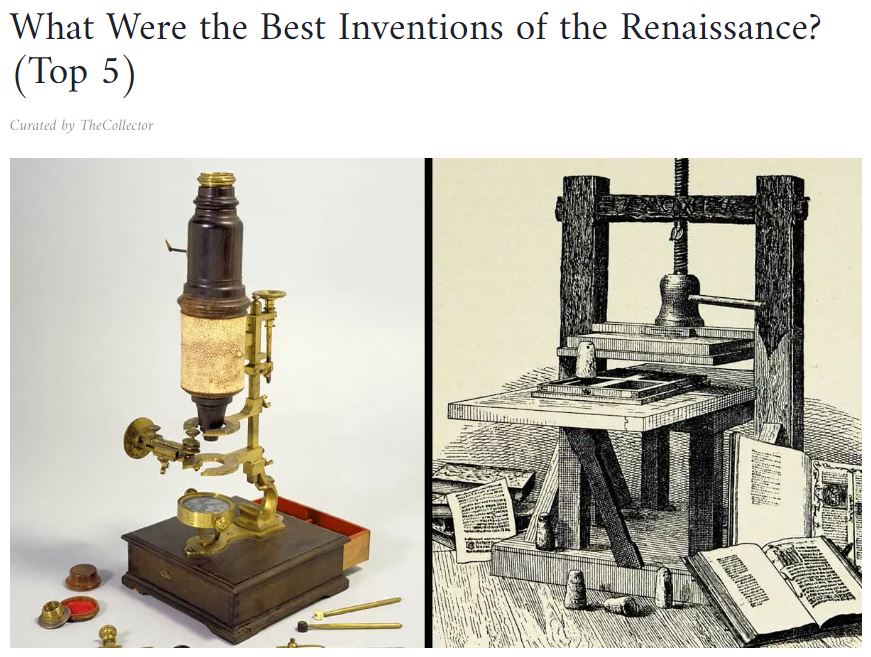

Renaissance intellectuals and artists revived classical motifs in the fine arts and classical values in literature and education. Intellectuals—later called humanists—employed new methods of textual criticism based on a deep knowledge of Greek and Latin, and revived classical ideas that made human beings the measure of all things. Artists formulated new styles based on ancient models. The humanists remained Christians while promoting ancient philosophical ideas and classical texts. Artists and architects such as Brunelleschi, Leonardo, Michelangelo, and Raphael glorified human potential and the human form in the visual arts, basing their art on classical models while using new techniques of painting and drawing, such as geometric perspective. The invention of the printing press in the mid-15th century accelerated the development and dissemination of these new attitudes, notably in Europe north of the Alps (the Northern Renaissance).

Three trends shaped early modern political development: (1) a shift from decentralized power and authority toward centralization; (2) a shift from a political elite consisting primarily of hereditary landed nobility toward one open to men distinguished by their education, skills, and wealth; and (3) a shift from religious toward secular norms of law and justice.

One innovation promoting state centralization and the transformation of the landed nobility was the new dominance of firearms and artillery on the battlefield. The introduction of these new technologies, along with changes in tactics and strategy, amounted to a military revolution that reduced the role of mounted knights and castles, raised the cost of maintaining military power beyond the means of individual lords, and led to professionalization of the military on land and sea under the authority of the sovereign. This military revolution favored rulers who could command the resources required for building increasingly complex fortifications and fielding disciplined infantry and artillery units. Monarchs who could increase taxes and create bureaucracies to collect and spend them on their military outmaneuvered those who could not.

In general, monarchs gained power through the corporate groups and institutions that had thrived during the medieval period, notably the landed nobility and the clergy. Commercial and professional groups, such as merchants, lawyers, and other educated and talented persons, acquired increasing power in the state—often in alliance with the monarchs— alongside or in place of these traditional corporate groups. New legal and political theories, embodied in the codification of law, strengthened state institutions, which increasingly took control of the social and economic order from traditional religious and local bodies.

However, these developments were not universal. Within states, minority language groups retained a more local identity that resisted political centralization. In eastern and southern Europe, the traditional elites maintained their positions in many polities. The centralization of power within polities took place within and facilitated a new diplomatic framework among states. Ideals of a universal Christian empire declined along with the power and prestige of the Holy Roman Empire, which was unable to overcome the challenges of political localism and religious pluralism. By the end of the Thirty Years’ War, a new state system had emerged based on sovereign nation-states and the balance of power.

Source: https://apcentral.collegeboard.org/pdf/ap-european-history-course-and-exam-description.pdf

Three trends shaped early modern political development: (1) a shift from decentralized power and authority toward centralization; (2) a shift from a political elite consisting primarily of hereditary landed nobility toward one open to men distinguished by their education, skills, and wealth; and (3) a shift from religious toward secular norms of law and justice.

One innovation promoting state centralization and the transformation of the landed nobility was the new dominance of firearms and artillery on the battlefield. The introduction of these new technologies, along with changes in tactics and strategy, amounted to a military revolution that reduced the role of mounted knights and castles, raised the cost of maintaining military power beyond the means of individual lords, and led to professionalization of the military on land and sea under the authority of the sovereign. This military revolution favored rulers who could command the resources required for building increasingly complex fortifications and fielding disciplined infantry and artillery units. Monarchs who could increase taxes and create bureaucracies to collect and spend them on their military outmaneuvered those who could not.

In general, monarchs gained power through the corporate groups and institutions that had thrived during the medieval period, notably the landed nobility and the clergy. Commercial and professional groups, such as merchants, lawyers, and other educated and talented persons, acquired increasing power in the state—often in alliance with the monarchs— alongside or in place of these traditional corporate groups. New legal and political theories, embodied in the codification of law, strengthened state institutions, which increasingly took control of the social and economic order from traditional religious and local bodies.

However, these developments were not universal. Within states, minority language groups retained a more local identity that resisted political centralization. In eastern and southern Europe, the traditional elites maintained their positions in many polities. The centralization of power within polities took place within and facilitated a new diplomatic framework among states. Ideals of a universal Christian empire declined along with the power and prestige of the Holy Roman Empire, which was unable to overcome the challenges of political localism and religious pluralism. By the end of the Thirty Years’ War, a new state system had emerged based on sovereign nation-states and the balance of power.

Source: https://apcentral.collegeboard.org/pdf/ap-european-history-course-and-exam-description.pdf

Early Modern Society

Objective: Explain European commercial and agricultural developments and their social and economic effects from 1450 to 1648.

Commerce, Agriculture, and Slavery: Crash Course European History #8

Let's look at the ways that individuals' lives were changing in Early Modern Europe. Some people's lives were improving, thanks to innovations in agriculture and commerce, and the technologies that drove those fields. Lots of people's lives were also getting worse during this time, thanks to the expansion of the Atlantic slave trade. And these two shifts were intertwined.

Agriculture

|

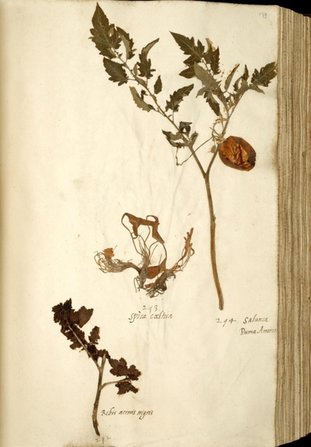

The Columbian Exchange introduced new staple crops to Europe, including corn, potatoes, and tomatoes, as depicted here in Solanum lycopersicum var. lycopersicum, the oldest tomato collection of Europe, 1542–1544

|

|

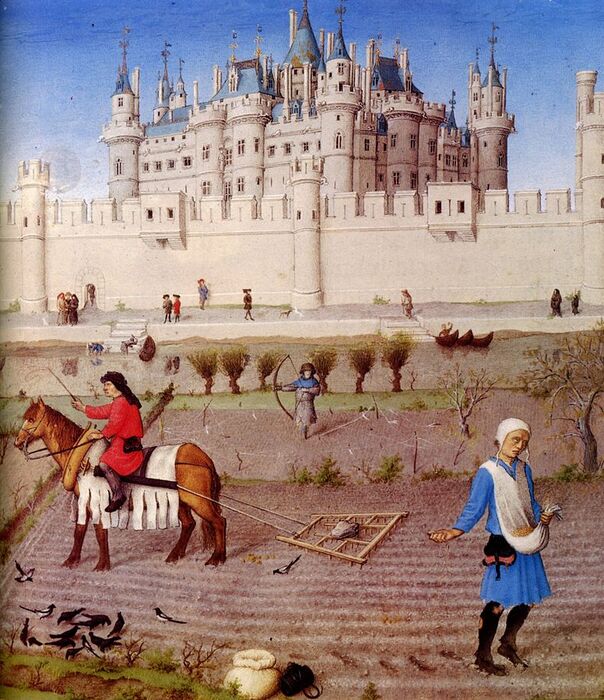

The peasants preparing the fields for the winter with a harrow and sowing for the winter grain, from the The Very Rich Hours of the Duke of Berry, c.1410

Towns and Cities

|

The Fish Market by Joachim Beuckelaer, c. 1568

|

|

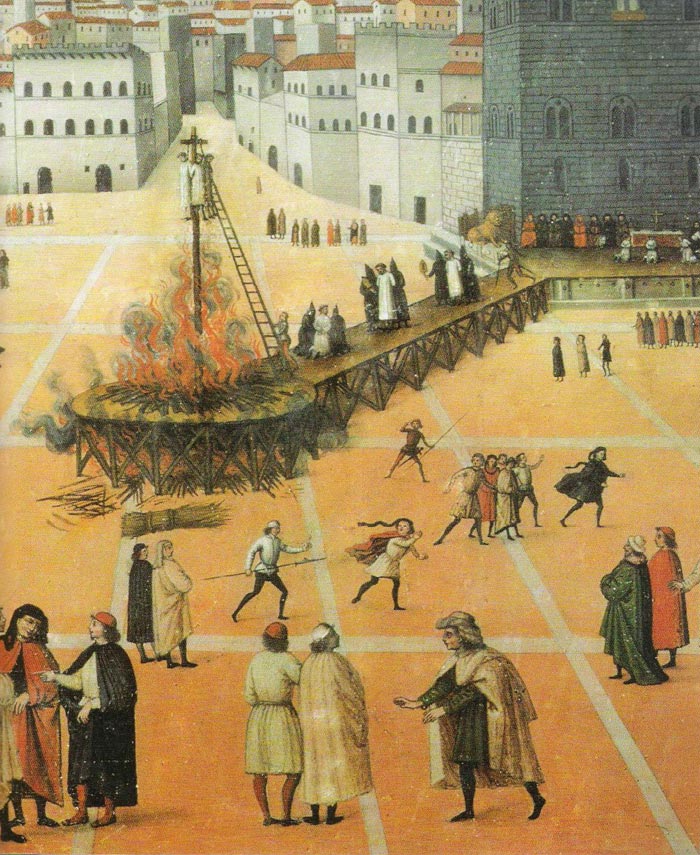

Public Morality

|

Execution of Girolamo Savonarola in Florence, 1498

|

|

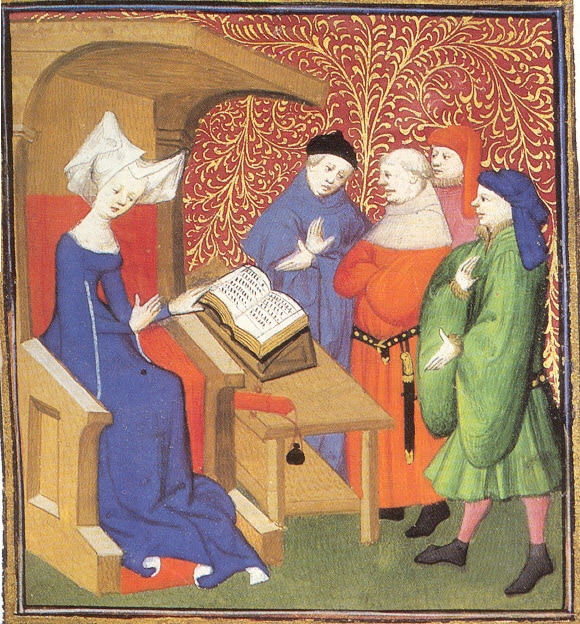

Women

Folk Culture

Carnival in Rome circa 1650

|

|

|

Early Modern Society Quizlet (comprehensive)

Agriculture, Serfdom, the Growth of Cities, Public Morality, Women, and Folk Culture, c. 1450-1648

Early Modern Society Quizlet (abridged)

Agriculture, Serfdom, the Growth of Cities, Public Morality, Women, and Folk Culture, c. 1450-1648

|

Renaissance

Italian Renaissance

Objectives:

- Explain the context in which the Renaissance developed.

- Explain how the revival of classical texts contributed to the development of the Renaissance in Italy.

- Explain the political, intellectual, and cultural effects of the Italian Renaissance.

Florence and the Renaissance: Crash Course European History #2

The Renaissance was a cultural revitalization that spread across Europe, and had repercussions across the globe, but one smallish city-state in Italy was in many ways the epicenter of the thing. Florence, or as Italians might say, Firenze, was the home to a seemingly inordinate amount of the art, architecture, literature, and cultural output of the Renaissance. Artists like Michelangelo, Leonardo DaVinci, Sandro Botticelli, and many others were associated with the city, and the money of patrons like the Medici family made a lot of the art possible. Today you'll learn about how the Renaissance came to be, and what impact it had on Europe and the world.

Il Duomo di Firenze (1436) by Filippo Brunelleschi

Jacopo de' Barbari produced the bird's eye View of Venice (1500), a monumental woodcut print.

|

Places:

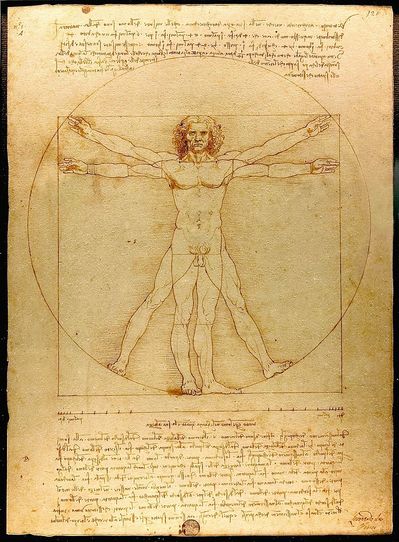

Leonardo da Vinci's Vitruvian Man (c. 1490) shows the correlations of ideal human body proportions with geometry described by the ancient Roman architect Vitruvius in his De Architectura.

|

|

|

The Italian Renaissance Quizlet (comprehensive)

The Italian Renaissance Quizlet (abridged)

|

Northern Renaissance

Objectives:

- Explain how Renaissance ideas were developed, maintained, and changed as the Renaissance spread to northern Europe.

- Explain the influence of the printing press on cultural and intellectual developments in modern European history.

The Northern Renaissance: Crash Course European History #3

The European Renaissance may have started in Florence, but it quickly moved out of Italy and spread the art, architecture, literature, and humanism across Europe to places like France, Spain, England, and the Low Countries.

|

|

|

|

The Northern Renaissance Quizlet (comprehensive)

The Northern Renaissance Quizlet (abridged)

|

The New Monarchies

Objectives:

- Explain the causes and effects of the development of political institutions from 1450 to 1648.

- Explain the technological factors that facilitated European expansion from 1450 to 1648.

- The struggle for sovereignty within and among states resulted in varying degrees of political centralization.

- The new concept of the sovereign state and secular systems of law played a central role in the creation of new political institutions.

- Monarchs and princes initiated religious reform from the top down in an effort to exercise greater control over religious life and morality.

- New monarchies laid the foundation for the centralized modern state by establishing monopolies on tax collection, employing military force, dispensing justice, and gaining the right to determine the religion of their subjects.

- Across Europe, commercial and professional groups gained in power and played a greater role in political affairs.

Political Theory

|

The New Monarchs unified their nations and created strong, centralized states.

|

|

The Military Revolution

|

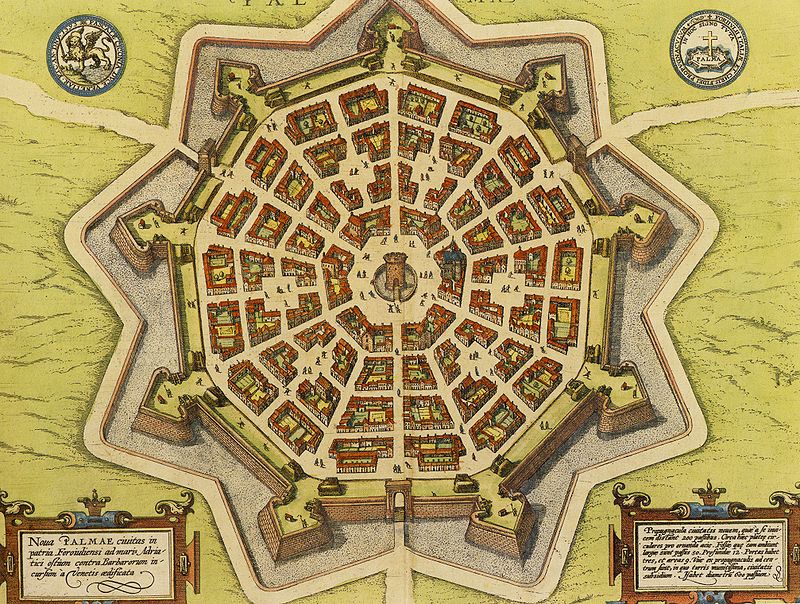

Fort Bourtange, a star fort completed in the Netherlands in 1593, gave guards a panoramic view of attackers.

|

Maurice of Nassau developed a standardized 43-step drill for musket volley fire.

|

The Embarkation of Henry VIII at Dover by James Basire (1540) showcases the Mary Rose, flagship of the English navy. Its wreckage was raised in 1982 in one of the most complex and expensive maritime salvage projects in history, as is now on display at the Mary Rose Museum.

Trastámara Spain

|

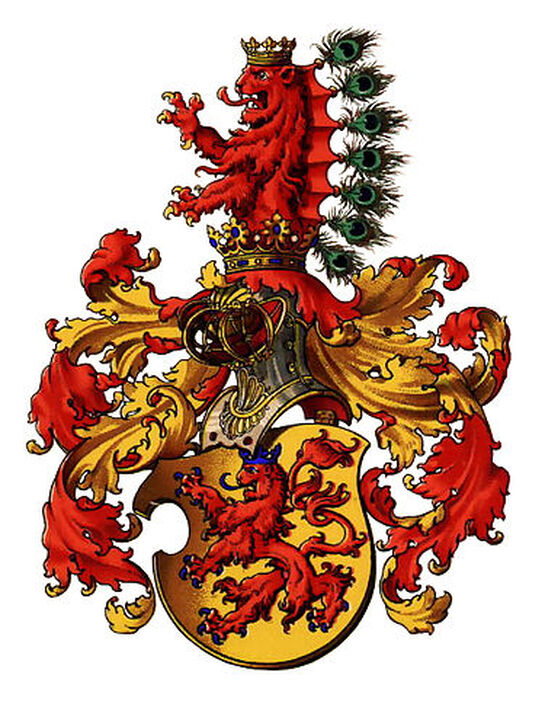

symbol of the Spanish Trastámara dynasty

|

IBERIA

|

Valois France

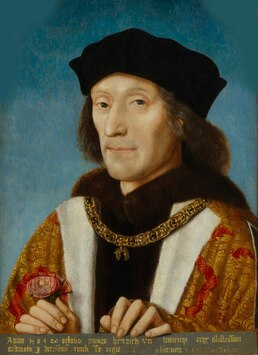

Tudor England

|

English Tudor rose symbol

|

ENGLAND

|

The Holy Roman Empire

|

symbol of the Austrian Hapsburg dynasty

|

War and Diplomacy

|

The Ambassadors (1533) by Hans Holbein the Younger portrays Jean de Dinteville and Georges de Selve, ambassadors of Francis I of France.

|

The Peace of Cateau-Cambresis (1559). Henry II of France and Philip II of Spain were in reality absent, and the peace was signed by their ambassadors.

|

The New Monarchies Quizlet (comprehensive)

The Military Revolution, the New Monarchies, Holy Roman Empire, Italian Wars, and Diplomacy, c. 1450-1648

The New Monarchies Quizlet (abridged)

The Military Revolution, the New Monarchies, Holy Roman Empire, Italian Wars, and Diplomacy, c. 1450-1648

|

Spain and England

Objective: Explain the causes and effects of the development of political institutions from 1450 to 1648.

English ships and the Spanish Armada during the battle of Gravelines, August 1588. A 48-gun Spanish galleass flies the Papal banner and the arms of Spain. The 55-gun English flagship flies the Elizabethan Royal Standard.

- The struggle for sovereignty within and among states resulted in varying degrees of political centralization.

- The new concept of the sovereign state and secular systems of law played a central role in the creation of new political institutions.

- Monarchs and princes, including the English rulers Henry VIII and Elizabeth I, initiated religious reform from the top down in an effort to exercise greater control over religious life and morality.

- New monarchies laid the foundation for the centralized modern state by establishing monopolies on tax collection, employing military force, dispensing justice, and gaining the right to determine the religion of their subjects.

Hapsburg Spain

El Escorial, Madrid, Spain (1563)

|

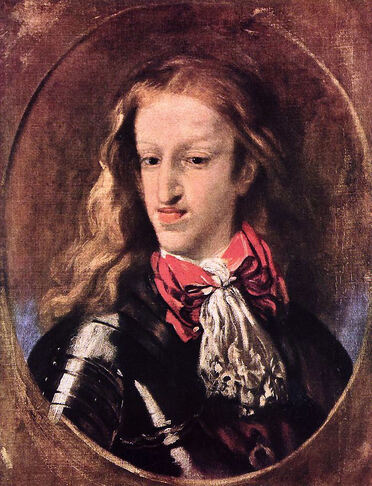

Hey, girl. Charles II of Spain was "short, lame, epileptic, senile, and completely bald before 35." The physician who performed his autopsy stated that his body "did not contain a single drop of blood; his heart was the size of a peppercorn; his lungs corroded; his intestines rotten and gangrenous; he had a single testicle, black as coal, and his head was full of water." (Morale of the story: don't marry your cousin.)

|

|

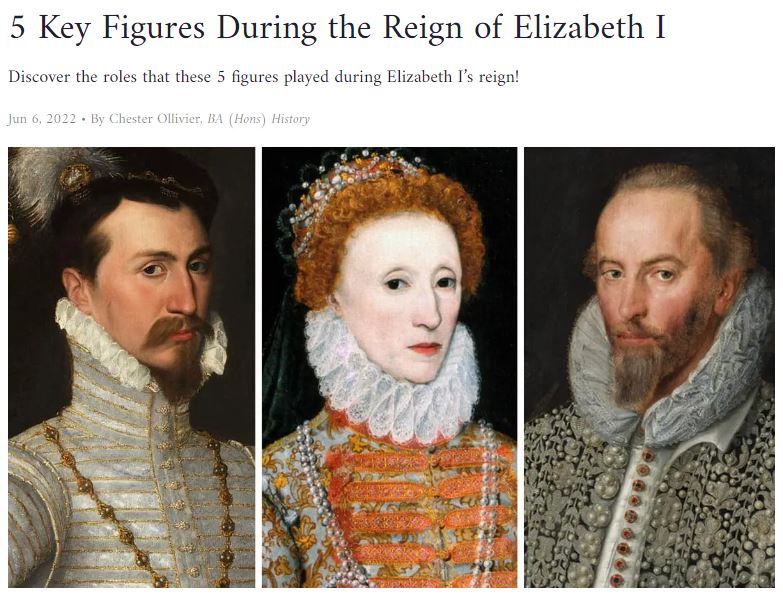

Elizabethan England

Portrait of Elizabeth commemorating the defeat of the Spanish Armada (1588). Elizabeth's hand rests on the globe, symbolizing her international power.

|

William the Conqueror ordered construction of the Tower of London as a new seat of royal power following the Norman conquest of England in 1066. By Elizabeth's reign, it was primarily used as a notorious royal prison. All English and British kings and queens since the 11th century have been crowned at Westminster Abbey. At least 16 monarchs and eight prime ministers are buried there.

|

|

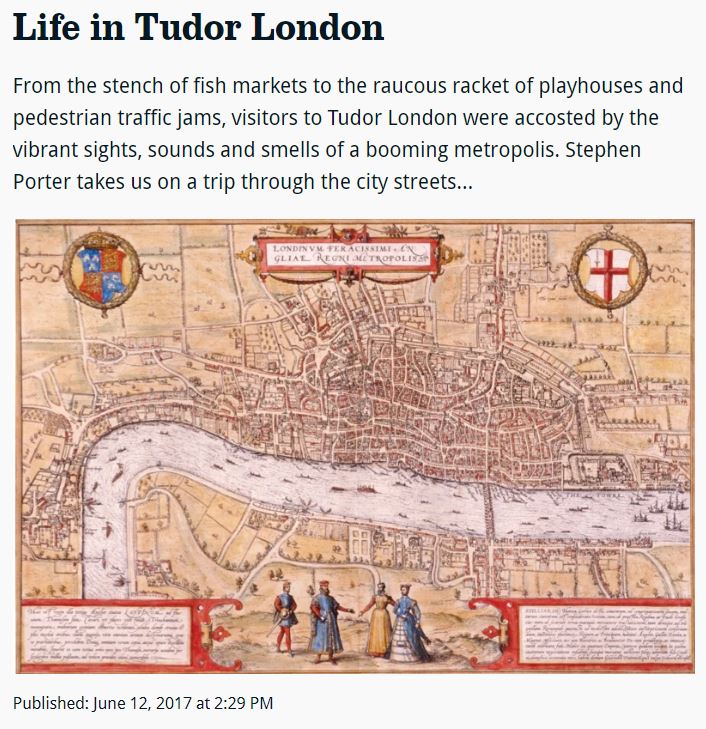

Article: Life in Tudor London

|

|

Hapsburg Spain and Elizabethan England Quizlet (comprehensive)

Hapsburg Spain and Elizabethan England Quizlet (abridged)

|

Sweden, Poland, and Russia

Objective: Explain the causes and effects of the development of political institutions from 1450 to 1648.

- The struggle for sovereignty within and among states resulted in varying degrees of political centralization.

- The new concept of the sovereign state and secular systems of law played a central role in the creation of new political institutions.

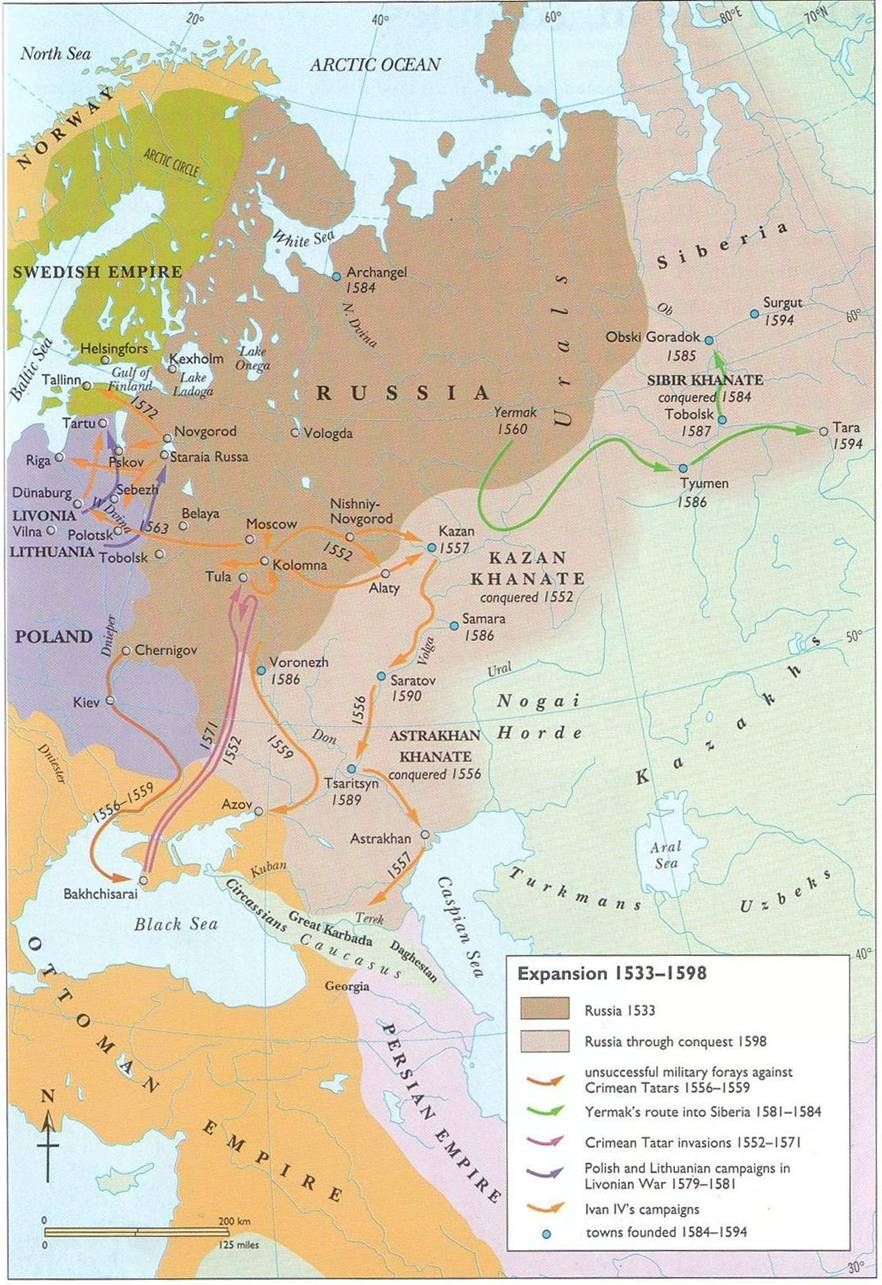

Eastern Europe Consolidates: Crash Course European History #16

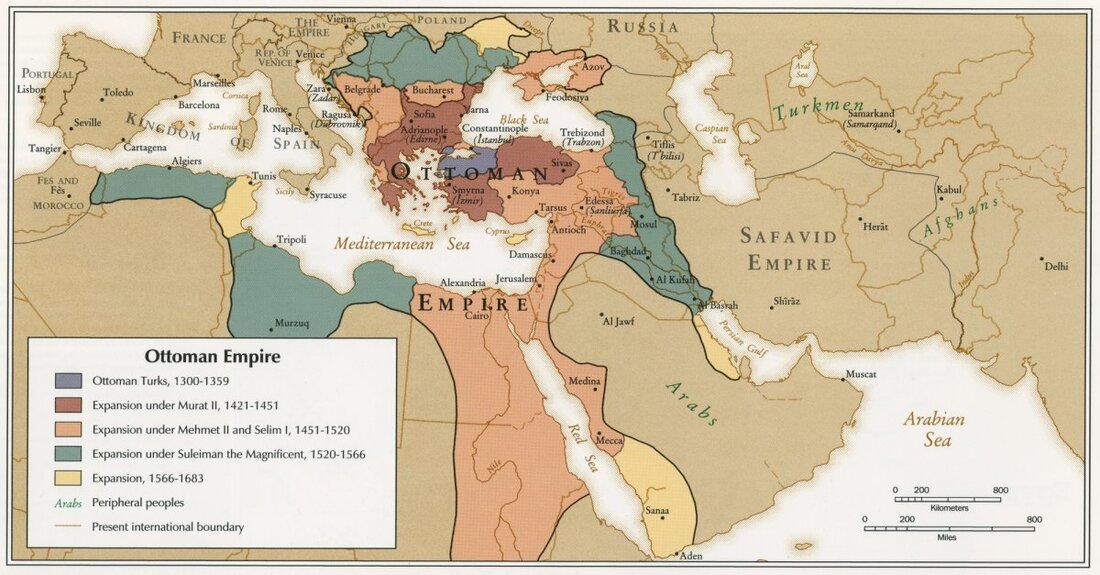

The Commonwealth of Poland-Lithuania, The Ottoman Empire, and Russia were all competing at the eastern end of the continent/landmass of Europe at during the 16th century. You'll learn about the various Ivans in Russia, and the Time of Trouble that followed them, and you'll learn about the Ottomans' expansion into Europe. You'll also learn how the great power you may not have heard of. Poland-Lithuania was right in the middle of all these events, from the rise of the False Dmitry to the Battle of Vienna.

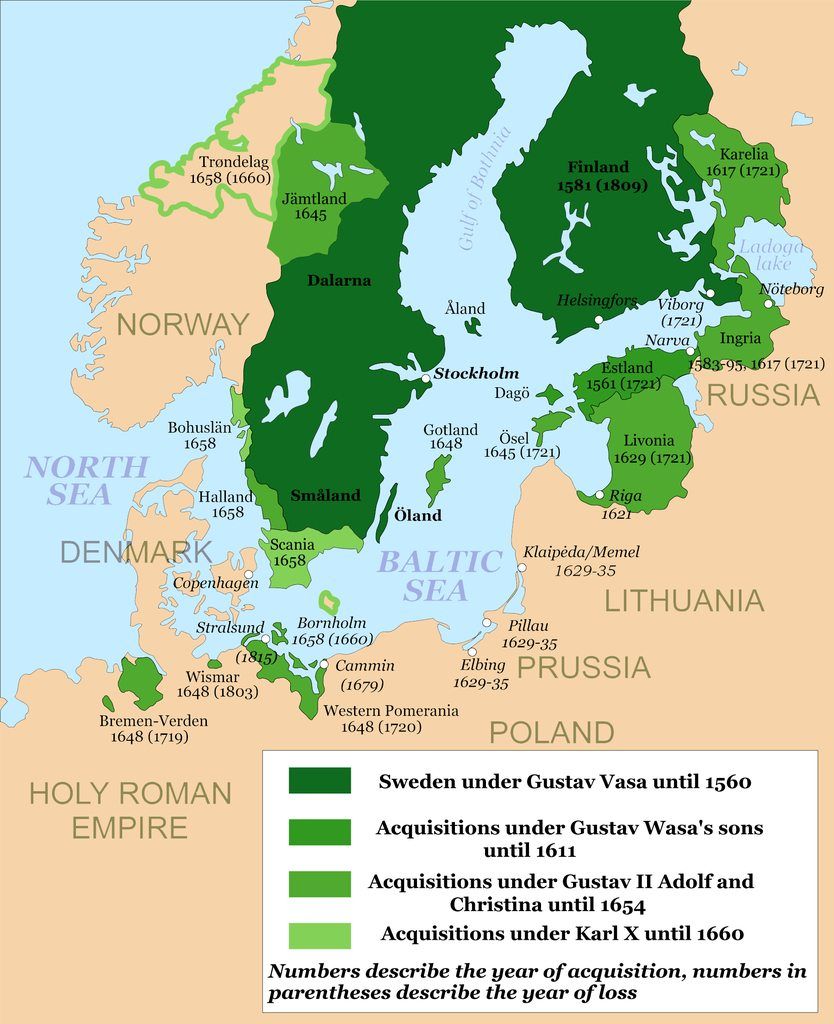

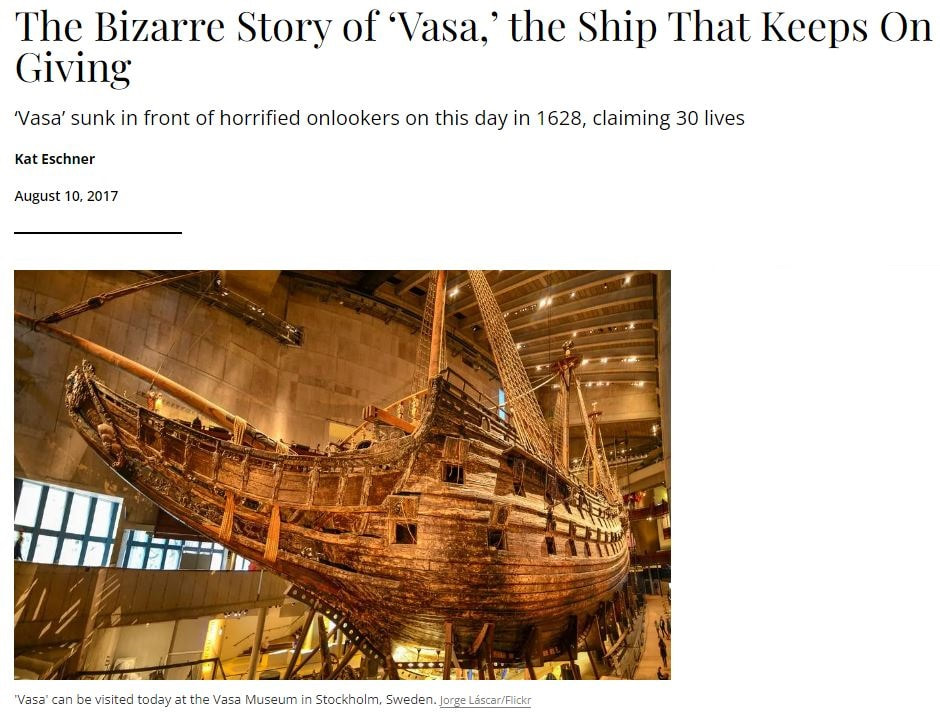

The Swedish Golden Age

|

Christina, Queen of Sweden, with her deep interest in art, religion, philosophy, mathematics and alchemy, made Stockholm a great center of learning. Either lesbian or gender fluid and rejecting traditional marriage, she has become an icon of the LGBTQ community. In 1654, she converted to Catholicism, abdicated her throne, and moved to Rome where she lived as a guest of several Counter-Reformation popes.

|

Tre Kronor Castle in Stockholm, Sweden

|

Commonwealth of Poland-Lithuania

Tsardom of Russia

St. Basil’s Cathedral, Moscow, Russia

The Ottoman Empire

Objective: Explain the causes and effects of the development of political institutions from 1450 to 1648.

Süleymaniye Mosque, Istanbul

Janissaries battling the Knights Hospitaller during the Siege of Rhodes in 1522.

|

|

|

Sweden, Poland, Russia, and the Ottoman Empire Quizlet (comprehensive)

The Swedish Golden Age, Commonwealth of Poland-Lithuania,

Tsardom of Russia, and the Ottoman Empire, c. 1450-1648 Sweden, Poland, Russia, and the Ottoman Empire Quizlet (abridged)

The Swedish Golden Age, Commonwealth of Poland-Lithuania,

Tsardom of Russia, and the Ottoman Empire, c. 1450-1648 |